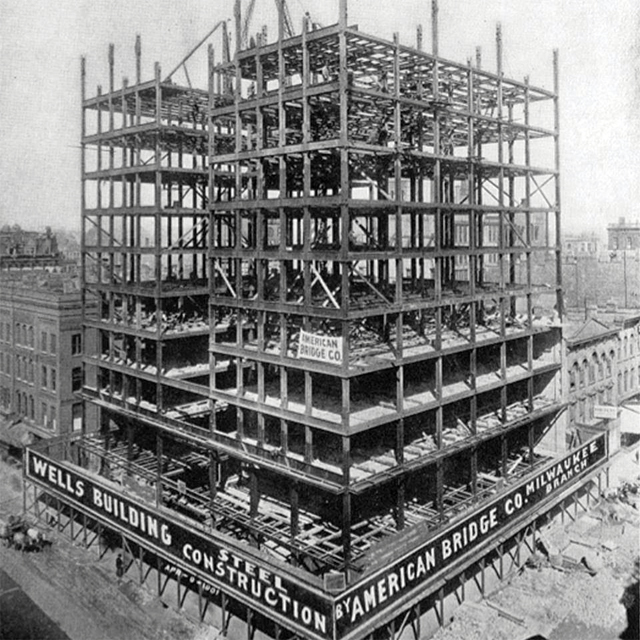

At many Milwaukee buildings history is layered atop history. And nowhere is that more true than at the Wells Building, 324 E. Wisconsin Ave., where the strata of history is topped with a hefty dose of spaghetti.

No, there’s no Italian restaurant in the 15-story office tower, built in 1901, instead the place – thanks to its long history as a communications hub – has countless threads of cable and wire everywhere: in the attic, in the basement, inside closets, coursing through old pipe runs (typically in conduit).

Because more than 30 carriers – including Verizon, Time Warner and AT&T (whose own wired-up local headquarters sits, not coincidentally, just a few feet away, across an alley) – lease space here, the Wells Building is Milwaukee’s own 60 Hudson St. (the downtown Manhattan telecommunications hub).

According to co-owner Eric Nordeen, every company serving Wisconsin has a presence here.

While few of these tenants have any human presence on site, their fiber optics and other gear for voice and data takes up as much as 25,000 of the building’s 130,000 square feet of space. according to Nordeen.

(PHOTO: Karl Herschede)

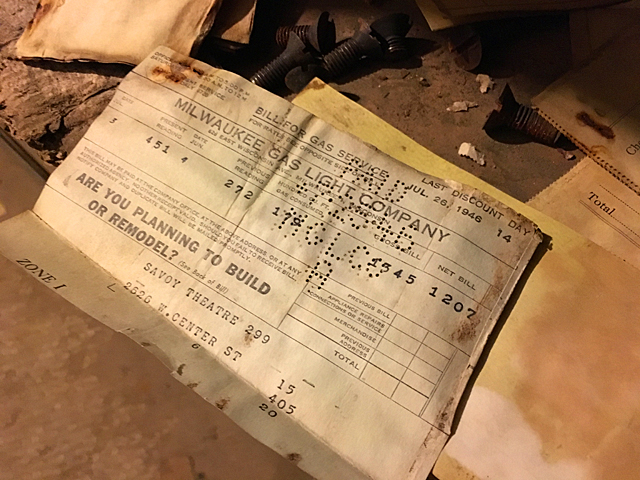

The building’s history as a communications center long pre-date the internet and cell phones. When Western Union Telegraph Company moved in and made the Wells Building its Milwaukee headquarters in the 1910s, the place became a key hub for information, much like 60 Hudson, which also was a Western Union site.

Even today in the Wells basement you can see a door with "Western Union" painted on the frosted glass pane and the area where a row of telegraph operators carried out their duties still bears signs of their presence (see above).

Though Western Union left the Wells Building in 1985, the structure had already long been wired for telephone service and had by then begun to be wired for the future.

But the building is more than the grease that lubricates your social media surfing.

Nordeen and his partner Matthew Prescott – who bought the building six years ago for just under $3 million – have been working hard to renovate and upgrade the dozen or so floors of office space into modern commercial space.

A lot of that has been transforming small, old-style (often single room) offices into open modern suites that offer not only the latest tech upgrades (of course), but also maintain the building’s historic feel.

Over the years, countless tenants have operated a wide variety of businesses in the Wells Building and a few, in addition to Western Union, have left traces. In the basement, there is a vault room, and there are old papers down there, too.

Beginnings

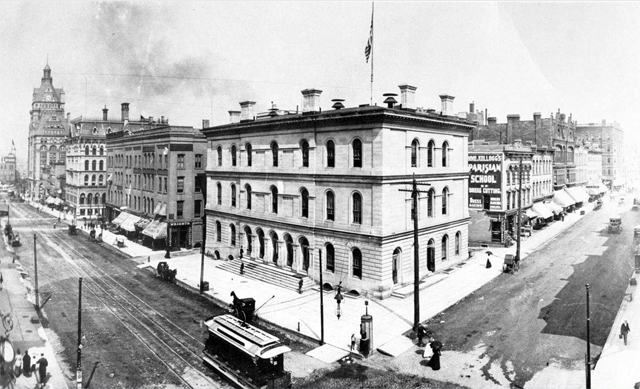

The site of the Wells Building has a long history and one that’s nearly always been tied to lumber magnate Daniel Wells Jr., at least since pioneer days.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Milwaukee Public Library)

Wells, born in Oakland, Maine, in 1808, moved to Milwaukee in 1838, where he worked in the timber and banking industries, before being appointed a judge and serving in the Wisconsin Territorial Council soon after his arrival.

In the 1850s he served two terms as a U.S. Representative and it was during this time that Wells was able to get nearly $90,000 appropriated for the construction of a U.S. Post Office and Customs House (pictured above) on a site where, according to Russell Zimmermann’s "Heritage Guidebook," he reportedly once fondly recalled hunting quail back when it was covered in hazelnut bushes.

Never one to pass up an opportunity, when the Federal Government decided to build a new post office and customs house further east on Wisconsin Avenue in the early 1890s, it sold the old three-story building to Wells, who rented it back to the government during the years it took to build the new Willoughby J. Edbrooke-designed place up the street.

Architect of his "monument"

When that opened, Wells was free to raze the old post office and tap no less than Henry C. Koch and Son to design what he hoped would become, notes Zimmermann, "his monument" on the site.

Though I’ve seen the building attributed to Henry himself, others have suggested that Koch’s son Armand designed the Wells Building and I’m inclined to believe Dennis Pajot on this assertion. In his well-researched book, "Building City Hall," he notes:

"Henry’s son Armand returned home from his schooling in Paris. The 29-year-old architect had won nine medals for competitive work in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and was ready to assist his father on the firm’s next big project. This was a 14-story office building planned for the railroad owner Daniel Wells, Jr. The building would be erected on the site of the old post office at East Wisconsin Avenue and North Milwaukee Street.

"The structure H.C. Koch & Co. planned had a 120-foot frontage on Wisconsin Avenue and could house 250 to 300 offices. It was to have a three-story base, topped with twin towers, rising 12 more stories. Koch said the building would be one of the most durable and substantial in the city, having a steel frame under the exterior of terra cotta and brick. The building was finished in 1901, and Henry Koch was proved correct, as the building still stands today, virtually unchanged..."

As stunning – and sturdy – a monument as it was (and is), Wells didn’t get to enjoy it. He died in March 1902 while construction was ongoing. He was 93. His heirs continued to own the building until 1970, when it was purchased by Towne Realty.

But the rest of us have been able to enjoy it for decades since.

Outside, and in

The structure is a 200-foot-tall Italian Renaissance skyscraper (atop that gorgeous multi-story base with its elegant copper cladding, broad windows and a lovely arched entrance) that remains one of the most striking in town, despite the fact that it lost the top four floors of exterior terra cotta ornament in 1960.

"Built in Milwaukee" – edited by Randy Garber – provides a nice description:

"A classical three-part composition: a two-story base with broad windows and an arched entry; a multi-story middle section of uniformly-spaced windows; and a terminal section with a bold projecting cornice rich in terra cotta decoration. It is evident that Koch had seen the work of Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, interpreting his designs rather than imitating them in the Wells Building. Although there is some resemblance to Sullivan in the general massing and ornamental scheme, Koch’s ornament is Renaissance rather than the Sullivanesque blend of naturalistic and abstract forms."

Inside, it gets even better, just inside the doors is a narrow vestibule with three mosaic domes (pictured above) and stunning tilework.

Pass into the marble clad lobby, which bursts with light, and marvel at the regal staircase and the terrazzo floor in which the word "Wells" can be read from either side.

The building has some interesting "secrets," too, for those willing and able to nose around.

Toward the back of the building is a solid and attractive iron staircase that would be the pride of many buildings, but here serves a utilitarian role.

And the real gems are in the sub-basement and at the top, which used to be spaces occupied by the Milwaukee Athletic Club. You can see what the club looked like here and here.

You can see the arched ceiling in the old Milwaukee Athletic Club gym. (PHOTO: Karl Herschede)

Founded in 1882, the club was a tenant in the building from 1902 until 1917, when it opened its own 12-story clubhouse – also designed by Armand Koch – around the corner.

Just under the roof, the MAC had a gym and elements of that space – which has long since been partitioned and otherwise altered – still remain, most notably the gym's broad arches (pictured above).

Especially exciting is that a few years ago, Nordeen, sensing something was up with the floor in the sub-basement, did a little cutting and spelunking himself and discovered the MAC’s old pool.

When I visited, we climbed down a makeshift staircase he opened up into the long-forgotten space and we could see the riveted structure of the pool, it's sloping floor and its tile.

Stepping down into this hidden bit of Brew City history was like wading into the city's forgotten past ... in a building that's wired for Milwaukee's future.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.