A lot of people have been working hard since last May to bring back Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church, 1046 N. 9th St., after the blaze that threatened the 1878 building’s very existence.

From the dozens of firefighters who battled the May 15 fire, to the folks who rescued precious objects the following day, to the Paul Davis crews who toiled to clear out muck four feet deep, to the engineers and Triad Construction crews who shored up the exterior walls and installed a temporary roof to allow reconstruction to begin – and beyond – hundreds have chipped in.

But two important team members have worked in quiet solitude, a pot of hot water for tea on the stove, in Wauwatosa to restore more than two dozen works of art that hung in the church and will be displayed there once again thanks to their skills and effort.

In late May, Monica Mull, who owns Art CPR conservation, preservation and restoration, received 25 works damaged in the fire and has since been working to restore them with the help of her assistant, Kelsey Soya.

Now, work on those objects – mostly photographs and prints, but also one plaster relief – is complete and Mull has returned them to Trinity, where they will hang in the recently re-opened offices until the church restoration is complete.

Before and after. (PHOTOS: Art CPR)

"I've been doing work for Paul Davis Restorations for about 18 years now," says Mull when we meet in her studio, located in a lovely Irish cottage-style house where she also lives. "I got the work through them. There are likely a number of other companies working on (objects from) the church, too."

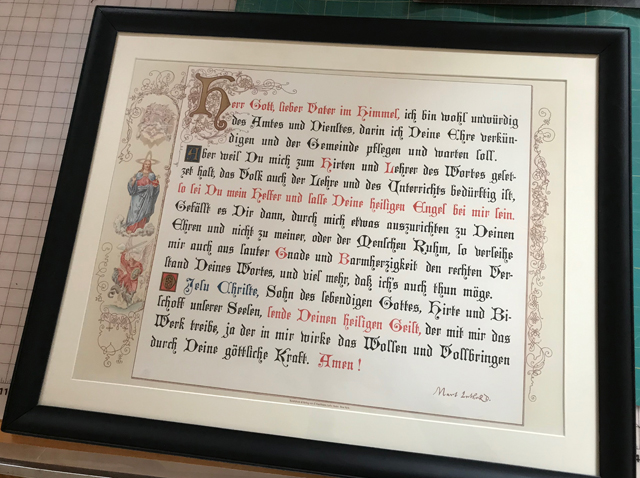

Among the works Art CPR received are photographs of the earliest pastors of the church, as well as yardlongs showing various groups. There is a print of a text in German and one showing the church choir members, which includes headshots of well-known Milwaukeeans with well-known surnames like Gettelman.

Mull received the works 12 days after the fire, at which point they (only one is unframed) were still in their frames.

"When I got them in they were soaking wet," she says. "Typically in fire damage you have plaster, insulation and gunk on the artwork that comes in. Water running down the front of the glass. The before pictures are kind of gory."

Those before pictures show various levels of water damage, mostly. You can see stains, especially along the lower portions of the works, because as you'd expect, Mull says, water tends to pool along the bottoms of the frames.

The dampness also caused many of the works on paper to warp and, in some cases, photographs that were unmatted in their frames became stuck to the glass. In one case, there was mold to battle.

"Normally I would just look at these and give an estimate and then wait for the insurance company to say go ahead," says Mull. "When it's a severe water damage, you kind of have to treat it like a triage situation and just stop what you're doing, get things out of the frames.

"I got these in at 4 in the afternoon and we just stayed up all night taking everything out of the frame and getting it dry. If we hadn't, all the photographs would have been stuck to the glass. All the pieces would have been moldy. I don't know how mold hadn't been growing already.

"Since we had everything opened up at once we were running fans just to start the drying process."

And then the real work began. Mull used a heat press to dry and flatten some of the works and water baths to remove stains. Damaged spots were touched up. Mats were re-cut. Frames and their glass were cleaned.

Some works required even more specialized techniques.

Like the silver gelatin photographic prints. In at least one case the gelatin that had gotten wet had adhered to the glass.

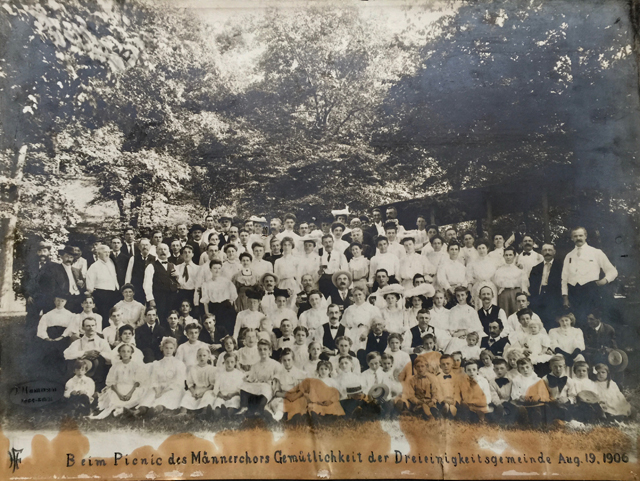

One of these 19th century photos, of a large group at a picnic, was beyond repair. In addition to being torn from top to bottom, it was heavily water damaged.

"It just couldn't be cleaned," says Mull. "It was a silver gelatin print and those can't be washed. The stain can't be removed. We had to restore it digitally. I had someone do the Photoshop, then we had to reprint it."

(PHOTO: Art CPR)

The digital version was cleaned up, printed and framed with the original photograph – which Mull stabilized as best as possible – mounted face-out in the back of the frame for anyone who wants to see it.

"That was the only one we just couldn't save," says Mull.

One of the most interesting works, and one in which Soya invested a lot of time, is a collage of headshots created by cutting the figures out of each original photo and mounting them into a single oval-shaped image (you can see it on the easel in the main photo above).

Whoever did the original work – which has no text to identify either the group or its members – also used ink to add highlights and contour to features on some of the individuals: slashes to define beards, curving lines to highlight a shoulder line, marks to add detail to washed out facial features, etc.

The plaster relief depicting the last supper was the only work that was not a photograph or print.

"There was a big chunk missing," Soya says. "We filled it. We painted different spots in with watercolor. Once we were done touching up, you can't tell."

Watercolor paints are used, adds Mull, because, "everything conservation should be reversible. That way in another 100 years or something when it's cleaned, they can take it off and redo it."

Mull is clearly enamored of her work, despite the fact that it typically results from tragedy, as she does a lot of restoration of objects damaged by fire.

"It's pretty constant work," she says. "There's always fires and floods. Sometimes I'll go out to the sites and see, or work on something there."

She hasn’t been inside the damaged Trinity, but she has seen many photographs of it.

"It's fairly interesting to see after a fire happens. The last one I went out to was a stove fire. I got to see the kitchen and the stove and everything all blackened. It's kind of scary. It makes me be safer out here. I don't leave things plugged in. I make sure the stove is off."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.