By Bobby Tanzilo | Published: June 29, 2017 at 1:01pm

This special feature originally ran in 2017 – but in honor of Summerfest's opening day, we've brought it back out for an encore.

Milwaukee has been called America’s most German city, and even as times have changed, much of our culture has roots in Germany.

Think beer and Usinger’s sausages. Think Mader’s and beer gardens. And Summerfest.

Yes, though it might not look much like it today, the roots of the World’s Largest Music Festival lie in Munich and its annual Oktoberfest tradition.

While Milwaukee had summer festivals before — notably the Carnival around the Court of Honor on Wisconsin Avenue at the turn of the 20th century, and the Midsummer Festival that ran nearly a decade from 1933 — Summerfest sprang from something else.

Milwaukee County Historical Society Curator of Collections Ben Barbera, who helped put together the "Summerfest 50 Exhibit" currently on view, agrees. "We could go even further back and look at (Mayor Daniel) Hoan, and Volksfest, and all these festivals they were having in the ‘30s.

"And in the ‘50s there was some chatter about how they wanted to do another big lakefront festival, but it wasn’t until Mayor Henry Maier came along and really was the driving force behind it."

As Barbera says, in the late 1950s, city officials began to talk about launching a new summer festival, and upon being elected mayor in 1960, Maier eagerly adopted the idea, and decided to check out Munich’s Oktoberfest, to get ideas for a festival with an international theme.

"The port city of Milwaukee is known for its strong German heritage and strong brewing tradition," wrote Paul Andrew Johnson in a UW-Eau Claire history thesis called "The Big Gig: Summerfest’s Evolving Role in the City of Milwaukee."

"Maier wanted to celebrate this heritage in the world festival. Howard Meister, the chairman of the new planning committee was sent to Berlin and Munich to evaluate their heritage festivals. He reported the many great things he saw. Meister was amazed at the vast size of each event. ‘Imagine beer halls holding 5,000 people with a band in the middle … They drink beer from 40-ounce pitchers and waitresses carry 15 pitchers without a tray.’

"Meister was quick to point out that it would be foolish of the city of Milwaukee not to exploit their beer making abilities; in fact, it could be the center of attraction. Ultimately, those who traveled to Germany realized it was no use for Milwaukee to copy such events. The planning committee and Maier wanted something unique; something both German and American."

By 1964, the Milwaukee World Festival committee — whose members, interestingly, included the likes of Vince Lombardi, Schlitz president Robert Uiheiln, Pabst president James Windham and Marcus Theatres’ Ben Marcus — proposed a 10-day festival. Ideas for events to be included ran the gamut, from polka to jazz, folk traditions to film, sculpture and flower shows and even a series of lectures by noted intellectuals.

"Maier had these grandiose notions of a little Olympics, and having all these celebrities here, and having it be more than a music festival, or arts festival, but having it be this whole huge thing," says Barbera.

In 1966, the committee suggested the name Juli Spass, which means "July fun" in German, but it proved short-lived, as many preferred something less specific to a single ethnic group, and soon the name Summerfest won out and by November the board settled on a nine-day slate of entertainment events that would take place the following summer.

That initial Summerfest was a big success.

"Summerfest opened on July 20, 1968, to the thunder of aerial bombs," wrote Steven Korris in his article "The Summerfest Follies," which ran in Wisconsin Interest magazine in 2001. "Visitors crowded into the Arena for the National Folk Festival, and swirled among dozens of activities all over the city."

There was a National Polka Festival, a two-night Music Under the Stars concert, air shows, an international auto race at State Fair Park, a soccer game, a women’s conference at Cardinal Stritch, The National Ballet of Mexico performed at the Auditorium and Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba played in Washington Park.

At the lakefront, near an old Nike missile site, a youth festival was held. Events were hosted at 35 locations. It was not much like the Summerfest we’ve come to know today.

"If you look at the schedule from ‘68, they basically lumped in a whole bunch of different events, and called it Summerfest," says Barbera.

"So there’s a car race, there’s an air show, there’s all these other things going on in addition to music acts, and theater acts and stuff like that. Those early years are really interesting, we actually have some scrapbooks and stuff with a lot of the newspaper clippings from that era, so it’s kind of neat to see."

Wrote Johnson in his thesis: "The Summerfest of 1968 intended to give all people of the city, no matter their social or economic place, a chance to experience a ‘kaleidoscope’ of new events and cultures. In fact, the events were spread throughout the city and only amounted to an average of a few per day during the nine-day festival.

"Many of the events, especially music concerts and venues by the lake, were free of charge. Generally the cost of an event did not exceed two dollars, making it feasible for most people and families to attend events. The location of the events made it accessible to many. … In conjuncture with the mayor’s goal to promote African-American culture, many events featured black performers. The Music Under the Stars concert series held in Washington Park, featured many ‘famous Negro entertainers from many parts of the country.’"

Because these were different times, Up With People! played three days during the first Summerfest and, Johnson noted, "drew thousands of people to each of their performances at County Stadium and Washington Park."

"If you had a picnic in your house with four people, you were part of Summerfest," quips longtime stage manager and board member Bob Milkovich, one of a select few to have been involved from Summerfest from 1968 until today. "Everything was Summerfest."

Although the festival didn’t finish with the financial surplus the committee had projected, 1.25 million people attended, so it was considered a success and it was believed the economic impact on the city was positive.

The following year, Summerfest followed the same format.

"The 1969 version of Summerfest was significantly bigger than the inaugural event," Johnson wrote. "The event coordinators kept several of the successful events the same from the previous year in hopes the events would be the anchor of the festival.

"The air show at General Mitchell Field was largely successful again, nearly a half-million people attended. Polka music remained in the spotlight as well. Legendary comedian Bob Hope headlined an event at Summerfest ‘69. The festival remained a local affair."

But big changes were on the horizon for Summerfest, which would soon return to the site of that 1968 Youth Festival — the former NIKE missile base along the lake — where it would go on to solidify its reputation as the Big Gig. And Milwaukee’s reputation as a city of festivals.

"Where else," says Milwaukee Department of City Development Commissioner Rocky Marcoux, "could you take a former Nike missile site and turn it into the world’s biggest music festival?"

Summerfest followed its big 1968 debut with an even larger — though still diffuse — schedule in ‘69.

Some things were reprised, like the popular polka events and the Mitchell Field air show, and others, like Bob Hope’s headlining gig, were new.

But the money didn’t follow and the festival ended deep in the red.

"Uncommon heat spoiled the fun and rain completely washed out the last day," noted Steven J. Korris in his article "The Summerfest Follies," published in 2001 in Wisconsin Interest magazine.

This speed bump, however, led to a major step in creating the festival that we know and love today.

"After the poor financial performance by the ‘69 festival, Summerfest was ready to move to a central location," wrote Paul Andrew Johnson in his UW-Eau Claire thesis, "‘The Big Gig’: Summerfest’s Evolving Role in the City of Milwaukee."

"If the festival was to be a ‘permanent attraction, it needed a permanent site.’ Summerfest truly became permanent in 1970."

That endurance would derive from its new home: a 15-acre former Nike missile site and airport on the lakefront, adjacent to the Third Ward and just south of Downtown.

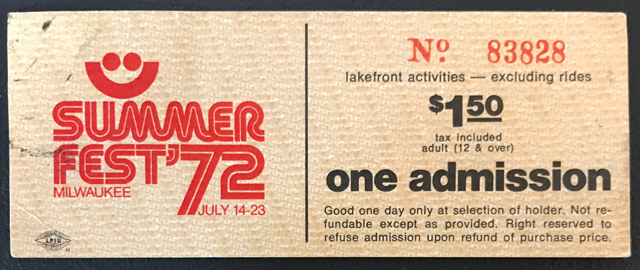

"(Mayor Henry) Maier and (board member John H.) Kelly … laid out a plan to bring the scattered events to the lakefront, charge an admission fee and shower corporate sponsors with publicity and free tickets."

There were other changes, too, that year. Former Packers standout Henry Jordan became the festival’s sales director — and, for some, its most public face — and Pabst, Schlitz and Miller all signed on as major stage sponsors.

For fans, 1970 was also the year that Noel Spangler and Richard Grant’s smiley face logo debuted and it was the first year for the Summerfest Pin promotion.

"(The grounds) still had that runway for small planes," remembers Bob Milkovich, one of the only people to be involved with Summerfest from 1968 to today, referring to the airport that had occupied the site.

"I think the new grounds took some getting used to, although I think what they liked was the location. It’s on the lakefront, perfect for sunny days, etc."

The result? More than a million people walked through the gates at Summerfest 1970, leading to a profit of more than $160,000, which meant there would indeed be a Summerfest 1971.

With growth comes growing pains, and crowd woes at shows by Sly & the Family Stone in 1970 and Humble Pie in 1973, as well as a controversial performance by (and arrest of) George Carlin, forced the Big Gig to reconsider its approach.

"One change that happened that was thought out was in the mid-‘70s, they made the very conscientious effort to transition from it being a rock ‘n’ roll show to being more family-friendly," says Ben Barbera, who curated the "Summerfest 50 Exhibition" at Milwaukee County Historical Society.

"And I think that was a big part of the lasting success. (With) some of the issues that went on, I think for Milwaukee, it would have been fatal. For this to be a centerpiece, and on the lakefront and all that, they had to make the change to it being a little more conservative, a little more family-friendly and a safer feel."

In ‘73, Milwaukee World Festival took over the Great Circus Parade and transformed it into the City of Festivals parade, foreshadowing the series of ethnic festivals that would begin setting up on the Summerfest grounds with the arrival of Festa Italiana in 1978.

That same year, Gooding’s Million Dollar Midway carnival opened on the south end and endured until it was displaced by the construction of the Marcus Amphitheater (now the American Family Insurance Amphitheater) in the mid-1980s.

The changes and the growth kept coming for the ever-Bigger Gig, and in 1974, the Schlitz Country Stage and the Pabst International Folk Festival Stage — run by Milkovich — were opened, joining the rock stage and the Miller Jazz Oasis. The Comedy Stage came the following year.

Also in ‘75, the festival invited area restaurants to come to Summerfest as food vendors, and the likes of Saz’s (who brought an annual T-shirt design along), Cedar Crest ice cream, Pitch’s, Wong’s Wok, Major Goolsby’s and Venice Club (mmmmm, deep-fried eggplant) all became popular fest noshes.

In 1977, Summerfest was hit by tragedy when Jordan — by then the festival’s executive director — died after suffering a heart attack after jogging. He was just 42.

However, 1977 was also the year Summerfest hired a figure who would become a defining part of the festival, a major player in its ongoing success, when it tapped Sheboygan native Bob Babisch as its new entertainment director.

"It happened so fast there was not time to think about it," Babisch told me. "I had been a stage manager at the Schlitz Country Stage the year before, and was working for a local promoting firm called the Edgewood Agency. It was April, and I got a call from the entertainment director of Summerfestm named Joel Gast, who said that the staff was leaving to start Chicagofest, and was I interested in his job.

"I went there the next day, and had a two-minute interview with the new executive director, whose name was Jim Butler. He handed me a one-year contract and said that I had until the next day to make a decision. The next day I said yes, and was there two weeks later. Because it was April, most of the acts were already booked for that year. The real nerves hit when I was responsible for the entire lineup the next year."

The lineup that Babisch booked for ‘78, which was also the festival’s 10th anniversary?

Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris, The O’Jays, Journey, Dolly Parton, Grateful Dead (whose show was canceled by inclement weather), The Bar-Kays and Cameo, Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, Bobby Vinton, Mac Davis and Boz Scaggs with the Little River Band.

A birthday preview party drew a whopping 25,000 people.

"The cleaner and quieter festival soon captured the public’s heart," Korris wrote of Summerfest in the ‘70s. "Attendance stayed above 500,000 a year, and the annual surplus grew. In 1979, under the leadership of board president John Schmitt, Summerfest made $423,034, bringing its cash balance to $1,101,385."

Summerfest was getting bigger and better. In the next decade, festival organizers would have to find ways to accommodate and build on that growth. A good problem for a festival to have.

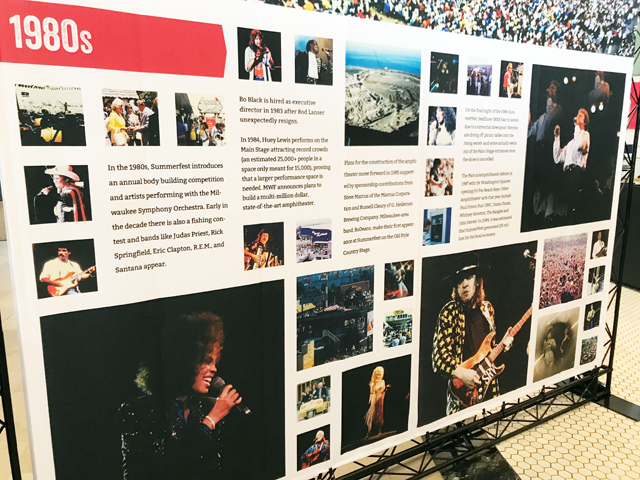

While Summerfest was in growth mode in the 1970s, the next decade brought the Big Gig to an entirely new level.

In the ‘70s, wrote Steven J. Korris in "The Summerfest Follies," his 2001 article in Wisconsin Interest magazine, "Attendance stayed above 500,000 a year, and the annual surplus grew. In 1979, under the leadership of board president John Schmitt, Summerfest made $423,034, bringing its cash balance to $1,101,385.

"Looking for ways to invest the hefty balance in continued growth," Korris continued, "he decided that a big amphitheater would attract the best possible shows. He convinced his board members, and they announced in 1983 that they would build it. They had spoken too soon, however."

At the same time, Summerfest Executive Director Rod Lanser — who replaced James Butler in 1979 — decided to call it quits, closing the door on one period and opening another for a new director who would become a star in her own right.

"Summerfest entered a new era in 1983 when Lanser unexpectedly resigned, citing job stress and health concerns," wrote Dave Tianen in his book, "Summerfest: Cooler by the Lake, 40 Years of Music and Memories."

"His replacement was a former (clothed) Playboy cover girl, NFL cheerleader, mayoral aide and professional fund-raiser named Elizabeth ‘Bo’ Black."

Taking over in 1984, Bo Black became not only the boss, but also the face of Summerfest for the next two decades. During her run, Summerfest and Bo Black became almost a single entity in the eyes of Milwaukee.

According to Tianen, Black was a superb fundraiser and a tireless promoter of the festival.

(On a personal note, the 1980s are when I met Summerfest for the first time. Just days before the 1983 festival, I moved to Milwaukee, where I knew no one. I spent a lot of time at the old Rock Stage on the south end of the grounds, seeing a young Stevie Ray Vaughan with Double Trouble, R.E.M., and locals like Violent Femmes, Colour Radio and Dark Facade. Thanks to invitations from my brother, I also experienced the old Main Stage for the first time, seeing Eric Clapton and Kool & the Gang.)

Black began her tenure when Summerfest needed to re-up its soon-to-expire lease and sign a long-term deal if Lanser’s dream of an amphitheater were to become reality.

Negotiations with the Board of Harbor Commissioners went on, literally, for years, but a deal was ultimately struck and the 23,000-seat amphitheater would be built on the south end of the grounds.

And not a minute too soon for the festival, which was already feeling the pain of its outdated main stage, according to Summerfest Entertainment Director Bob Babisch.

"Around the time the amp finally got built, we were already in the process of losing big shows," Babisch told me. "Not only because we did not have the capacity — the old main stage could only hold 16,000 people — but because we could not put the production in that touring acts were starting to bring on the road.

"The last roof on the old Main Stage had a pipe running across the middle of the stage about 15 feet above the ground. The pipe was part of the infrastructure of the stage. Because bands were taking out lighting rigs that needed a height of 20 to 25 feet minimum, we started to lose shows. We also could not put much weight on the roof, so we could not ‘fly’ (hang) sound cabinets.

"With other buildings and venues having more capacity — anywhere from 18,000 to 30,000 — we were losing the names that are needed to be called a first class event."

This situation was made woefully apparent at the 1984 festival, when more than 25,000 people turned out to see Huey Lewis & the News perform at the 14,000-seat Main Stage.

The new venue, with covered seating sloping up from the stage — which faced the lake — and a grassy, uncovered seating area, was much like a number of similar venues constructed around the country at the time.

It cost $12 million and was funded by bond sales and donations of $2 million from the G. Heileman Brewing Co. and $1 million from the Marcus family, whose name was attached to the facility until this year.

The new stage surely helped Summerfest continue to grow. According to Korris, attendance at the Big Gig jumped from 671,412 in 1986 — the year before the amphitheater opened — to 873,235 in 1996 — a 30 percent boost.

According to Summerfest, it was estimated in 1989 that the festival generated $35 million for the local economy.

In its first year, the Marcus Amphitheater hosted the Beach Boys, The Bangles, Dolly Parton, Paul Simon, Run-DMC, Duran Duran, Jimmy Buffett, Chicago, Bruce Hornsby & The Range, John Denver with the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, and Whitney Houston.

Before the ‘80s were over, Stevie Wonder, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart, Sting and others would perform there.

Once again the start of a new Summerfest chapter would coincide with the end of another.

"The 1987 celebration also marked the final bow of the man acknowledged as the Father of Summerfest, Mayor Henry Maier," wrote Tianen in his book. "The retiring mayor visited the grounds and led a sing-along that included two songs of his own composition, ‘The Milwaukee Summerfest Polka’ and ‘Mayor Maier’s Farewell,’ written specifically for the occasion.

"For his farewell visit, the mayor repeated his often-stated view of the Summerfest mission: ‘The ordinary guy in Milwaukee and outside of Milwaukee, who did not have a membership in a country club or didn’t have a country home on a lake, needed a place to go and things to do in the summertime’."

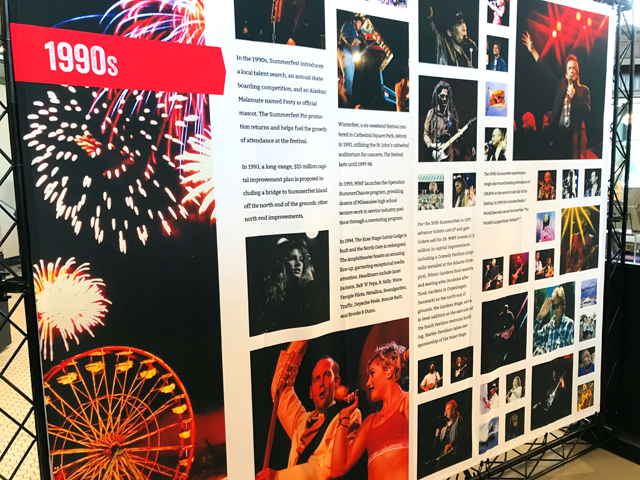

While Summerfest was finding its legs in the 1970s and growing bigger and bigger in the 1980s, the following decade was more one of building on the success of the Big Gig, entrenching it deeper into the Milwaukee psyche and lore.

At the beginning of the decade, for the 1990 festival, Summerfest brought back its popular pin promotion, which had debuted at the 1970 and later been discontinued.

The pins allowed purchasers to enter the festival for free every weekday afternoon. They also became beloved collector’s items.

"I have all the pins," says Denise Tanzilo, my sister-in-law, and devoted Summerfest pin collector. "I have doubles of most — I got some doubles from friends and sales. I keep one pristine set and I wear the others. I display them on a lanyard that I wear only during Summerfest.

"My favorite is the old snorkel one. My second fave is the 1990 sunglasses guy. I never used to wear the gold ones. I just saved them, but that wasn’t fun, so now I wear them, too."

The pins also helped Summerfest continue to bolster its revenues, according to Dave Tianen, who wrote in his book, "Summerfest: Cooler by the Lake, 40 Years of Music and Memories:"

"Since the pins were sold in the weeks before the festival opened, they also provided Summerfest with a revenue buffer against the potential of lower attendance because of bad weather."

The program ended again in 2003.

"I was sad when they stopped," says Tanzilo. "They should start again. I have suggestions."

Promotions were a big boost for the Big Gig in the 1990s. In 1997, Tianen wrote, "a survey found that 21 percent of Summerfest attendees used some kind of discount to purchase their admission."

Later in the decade, in 1998, the festival set a single-day attendance record on the penultimate day of Summerfest as 138,854 people passed through the gates. That led the Guinness Book of World Records to name Summerfest the World’s Largest Music Festival the following year. It’s a sobriquet that the festival has used ever since.

With growth came the need for improvements on the grounds, too, and the 1990s found a number of big changes at the Henry Maier Festival Park.

A $15 million capital improvements plan was proposed and four years later, Summerfest got a new North Gate, a permanent stage was built for the Koss Stage/Leinie Lodge and the Potawatomi Bingo Casino/V100 Soul Stage was launched.

In 1997, Summerfest added the Comedy Pavilion, which it shipped up from its former home at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, the Gardens Stage and the Ethnic Gardens food and seating area near the north end.

The same year, Harley-Davidson began its sponsorship of the former Pabst Stage.

But the biggest change was just offshore.

In 1991, a new 17-acre island was created by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, along with the City’s Board of Harbor Commissioners using limestone and granular fill from the deep tunnel project.

The new island offered a safe harbor for small boats just off the Summerfest rocks and also helped prevent erosion along the festival grounds. It also provided a great place from which to launch fireworks displays.

In 2007, it became one of two urban state parks in Milwaukee (along with Havenwoods) that has proved popular with bikers, walkers, joggers and others. It was the first new state park since 1978.

Some other interesting moments and facts from Summerfest in the 1990s…

If Bo Black was a big part of the story of Summerfest in the 1980s and ‘90s, her departure was one of the early landmarks of the first decade of the new millennium.

According to Dave Tianen’s book, "Summerfest: Cooler by the Lake, 40 Years of Music and Memories," tensions that arose during negotiations of a new lease for the Henry Maier Festival Grounds were the beginning of the end of a 20-year relationship between Black and the Big Gig.

"The (new) lease agreement revealed tensions within the Summerfest family that undermined Bo Black’s once unassailable position as executive director," he wrote, pointing out that once the deal was done, Black — who had been feuding with then-Mayor John Norquist already — publicly criticized the lease.

"Signs that Black’s position had dramatically eroded were evident when the board declined to take up the matter of her contract extension at its December 2002 meeting. In September 2003, the Summerfest board voted to dismiss Black."

And so ended the longest run by a Summerfest executive director in the history of the festival so far.

Black left a few recent highlights behind when she departed. In 2001, Summerfest broke the 1 million mark in attendance for the first time. The Emerging Artist Series was launched at the U.S. Cellular Connection stage at the 2004 festival, the planning for which began while Black was still at the helm

In 2003, a number of improvements were made to the grounds.

A new permanent rock stage was erected on the north end, along with a north gate ticket office and new restrooms. A new mid-gate was constructed, too with ticket windows, food vendor buildings, a second floor seating area in the nearby Harley-Davidson Roadhouse and, best of all, the mid-gate pavilion area with its immediately popular splash pad.

On the south end, the carnival rides were removed and replaced with a new M&I Bank-sponsored stage.

But even more dramatic changes to the grounds would follow when new executive director Don Smiley took over in 2004.

A Racine native, Smiley — who had been working in Florida as executive director of the PGA Tour’s Honda Classic — was hired by businessman Wayne Huizenga to help grow Blockbuster Video, which he did, taking it from just 10 video rental outlets to more than 3,000 worldwide.

"Right at the tail end of that, we had thrown our hat in the ring to pursue a national east Major League Baseball franchise for South Florida," Smiley recalls. "There were eight other cities that were vying for a team, and I headed up the effort for him along with three or four other folks, and we were granted a team in July of ‘91. We threw out the first pitch in April of 1993, and we won the World Series in October of 1997."

At the same time, the Marlins stadium was also hosting big concerts by the likes of Billy Joel, Elton John and the Rolling Stones, giving Smiley an intro to the concert business. But that’s not how he came to Summerfest.

After Huizenga sold the Marlins and Smiley left, he moved to North Carolina.

"I was playing golf one day with a recruiter from New York, and he took a phone call in the golf cart, and they started talking about Summerfest," Smiley says. "I could hear one side of the conversation, and I said, ‘you’re talking about Summerfest.’ He said, ‘Yeah, how do you know about that? Oh, yeah, you’re from Racine!’

"He put two and two together, and couple of holes later he said, "You know, I have the assignment to find a president and CEO for that organization, would you be interested? I said, ‘Jeez, I don’t know, I’ve never thought about it, you know?’ And so I said, ‘Give me some information, let me look at it.’

Soon after, Smiley — whose name would seem to have made him a shoo-in for the job at the festival with the smiley face logo — was in Milwaukee as Summerfest’s new executive director.

The affable Smiley says he didn’t know much about Bo Black and wasn’t at all intimidated by her public stature in Milwaukee.

"I never really looked at it that way, I mean I don’t look at myself that way, I don’t operate that way," he says. "The event is the celebrity. No one person is. Celebrities are Brewers players and Packers and Bucks. I really don’t know much about that whole situation prior to me getting here, what she was or what she wasn’t. I didn’t really focus on that, I really focused on the job that I wanted to get done.

"And, you know, I just came off winning the World Series. I didn’t need to be out there more when I got here. I had just gone through that. I was very experienced with the media, but I never searched it out."

By the time he got here in 2004, Smiley says the festival was already planned, so he spent his first Big Gig exploring, taking notes, learning and formulating a plan for the future. And that plan focused heavily on the grounds and facilities.

"To be brutally honest, I mean, the grounds were just a mess," Smiley says. "They were just tattered and torn. The south gate … There was a temporary stage in the south end known as the Classic Rock Stage. The Briggs and Stratton stage was in tough shape, the Harley stage was in tough shape, the Miller stage was in tough shape. Basically, every single one of the stages needed to be demolished and rebuilt.

"It was a little bit of a daunting task, because, you know it’d be one thing if there was just one stage that needed to be redone. But the whole place needed work. They hired me to come in here and improve things. So I did. And I ended up, along with many others, coming up with a plan to rebuild this place."

Smiley felt that there was too much emphasis placed on attendance numbers; on hitting that 1 million mark. He was going to take a different approach.

"There seemed to be an inordinate amount of weight given to this attendance number and very little weight to the actual physical property that Summerfest operates on," he says. "You’re running all these people through your property, and your buildings aren’t really in very good shape, whether it’s bathrooms, restaurants, stages, whatever.

"So, I just flipped that around and said, "look, we’re going to take the emphasis off of attendance, and we’re going to think about quality. We’re gonna think about fan-facing elements of this festival, that a fan touches, sees, interacts with, that is additive to their experience at a concert or festival’."

So, he set about the work, focusing first on the Miller Oasis, which was revamped for 2006. Then came the Harley Roadhouse in 2008. And the work has continued apace ever since. So much so, that this year, the Miller Oasis has gotten the second massive makeover of Smiley’s 14-year tenure.

The next decade would find Smiley continuing to improve the guest experience on the Henry Maier Festival Grounds. Next week, while the Big Gig is taking place at the lakefront, we’ll look at the 2010s in this Summerfest decade by decade series.

As soon as he arrived as Summerfest’s new executive director in 2004, Don Smiley set about improving the grounds and facilities as a means for improving the guest experience at the Big Gig.

"I don’t know what folks focused on in the past, but I was going to focus on the property," Smiley recalls. "Because if something wasn’t done pretty quickly, you know, they would’ve started losing stages. I mean literally falling apart.

"I looked at the structures, and the buildings, and the land, and how are we going to make this a more pleasant experience for the fans versus just a 12-hour frat party, 11 days a week."

That work continued, full steam ahead, in the second decade of the new millennium.

In 2010, a number of improvements arrived, including a new South Gate entrance and box office, a new Briggs & Stratton Big Backyard Stage with a raised viewing deck, additional restrooms, new restaurant buildings and upgrades to the Summerfest parking lots.

Two years later, the most exciting development in years arrived as Summerfest opened the BMO Harris Pavilion, a covered stage with fixed seating, state of the art sound, lighting and video screens.

"When you have temporary stages they can be dangerous in high winds, and, you know, God forbid a tornado comes through or something. So I really wanted to get away from anything temporary. Or really minimize it. And that’s why we ended up building the BMO Harris Pavilion, with a roof on top and so on."

In addition to allowing the Big Gig to book acts a little too big for grounds stages but perhaps not quite Amphitheater-ready, the BMO Harris Pavilion has served as a place where Summerfest can host concerts outside the 11 days of the festival.

"We’re do co-promoted ventures with (The Pabst Theater Group’s) Gary Witt at the BMO building," says Smiley. "Some we do on our own, some we do with Gary. I just think we’re to the point where we’re getting to a nice trajectory, and we can do more. Yeah, I see more of that. It’s fun working with Gary and his company, he has very experienced people. And we do good things together. If he wasn’t a good operator, with honesty and integrity, we wouldn’t be interested, but he’s just the opposite, so we will do more."

The same year, Summerfest launched another extra-festival event, the Summerfest Rock ‘n Sole Run, which includes a 5K, and quarter- and half-marathon races — in addition to a kids’ race — which provide runners a route with a view, as the courses go over the Hoan Bridge above the Henry Maier Festival Grounds.

"It really came down to we have all this talent around here, so let’s do more events," says Smiley. "So we started with the race. There weren’t many half-marathons, and quarter-marathons, when we started. Now there’s, I don’t know, six, seven or eight of them? We also do the Big Gig Dress Rehearsal on Saturday night (before Summerfest). That’s to kick off the entire week of Summerfest."

In 2014, Summerfest brought back a Ferris wheel, setting it up on the north end of the grounds, where it not only offers great skyline and lake views to riders, it serves as a beacon for folks to see the festival taking place.

While Dave Matthews Band’s 2014 Amp show holds the record for most tickets sold for a Summerfest headliner (22,358), the next two years offered what have surely been the most anticipated and exciting performers in the Big Gig’s history.

In 2015, The Rolling Stones rocked the Amphitheater and in 2016 Paul McCartney played to an adoring crowd.

That left Summerfest in the unenviable position of finding a way to top those shows for its big 50th anniversary celebration. But Smiley is undaunted.

"How do you top it," he asks aloud. "There’s plenty of big supergroups out there yet, and we’ll get our chance at several of them over the years, but you know, to have a back to back deal like we did with the Rolling Stones and McCartney …

"If you look at our lineup (for 2017), we’re selling more tickets than we did last year as a whole, for all 11 days, which attests to a very balanced lineup. We have something for everyone, and tickets are really selling well. People ask us all the time about Adele, and they ask us about U2, they ask us about Taylor Swift, you know, Justin Timberlake. And you know, these are deals that we work on. But sometimes these deals, especially the mega-deals, they just take time."

As for time, it has flown by for Don Smiley, who can hardly believe he’s now been in the driver’s seat at Summerfest for 14 years. And he’s showing no signs of slowing down, either.

"It just has been a blink of an eye," he says. "When I look back on all the shows that we’ve done, and all the artists that have come through here, and all the productions that we’ve done, it’s just amazing to me how fast this time has gone here.

"I really don’t think about (leaving). You know, as long as I feel good, which I do, and as long as I’m challenged, and I am, and as long as I enjoy the people I work with, which I do. I’ve had outstanding boards, to work with, board of directors, over my time, they really let me do my job. So all of that is just excellent, it’s just a plus. I’ve met so many good friends here in Milwaukee."

Smiley’s commitment to the infrastructure of the Henry Maier Festival Park and how it affects the Summerfest patron’s experience remains a driver for him.

"By the time I’m finished it will definitely be rebuilt," he says, "including the new amphitheater. I don’t think about legacies, I just think about contributions. Contributions that may have been made on my watch by a large team of people, not just me, I ask, ‘did the fans really benefit from those changes?’ And I think they do, and I think they like it. And I think they’ve grown to expect it.

"We’re going to be busy. Now we’re going to open the Miller Lite Oasis, and after this festival season, we will demolish the U.S. Cellular stage and rebuild that entire footprint, and we’ll open that stage for Summerfest 2018. After that stage is completed, then we will demolish the American Family Insurance Amphitheater in the fall of 2019, rebuild it over the winter and open it by Summerfest ‘20."

A new North Gate and plaza will also debut in 2018. In fact, since Smiley’s arrival, Milwaukee World Festival has invested more than $70 million in the Henry Maier Festival Park, including a new administrative building in 2015.

"We really have our plate full, I mean not only are we, you know, getting prepared to open for the 50th edition of Summerfest, we have, our plate is overflowing with things to do in ‘18, ‘19 and ‘20."