You can’t miss it. The soaring Victorian Gothic bell tower of St. Michael’s Catholic Church, 1445 N. 24th St., while only briefly the tallest in town, is definitely the tallest in its surrounding neighborhoods, where it can be seen from all around.

And, if you pay attention to such things, you can’t miss that it’s a Schnetzky & Liebert-designed church, either. Those four small turret-like, cross-topped octagons on the corners of the bell tower are a dead giveaway.

You can see variations – some cylindrical, others not – on the Bronzeville church the duo designed, on their St. John's Evangelical Lutheran Church in Two Rivers. On Herman Schnetky’s 1887 St. Martini Lutheran Church – before he partnered with Eugene Liebert – those are pointed little canopied spires, quadriform not round. But at St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran and St. Lucas in Bay View, built soon after – when Liebert was a draftsman in Schnetzky’s office – variations on the turrets are there.

As a fan of the work of Schnetzky & Liebert, exploring St. Michael’s has long been on my wish list. Recently, in advance of the 175th anniversary celebrations – slated for November, details are here – of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, I got that chance.

St. Michael’s Parish

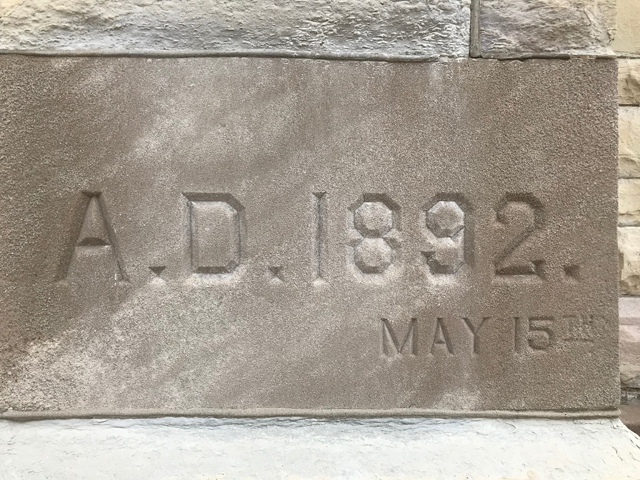

The St. Michael’s congregation dates to 1883 to help accommodate the rapidly growing West Side neighborhoods in the city. It was the fifth German-language Catholic parish in the area. A series of buildings was erected, including a parsonage and a combination church and school, though only the 1885 School Sisters of Notre Dame convent (facing Vliet Street) still survives. (Later school buildings face North 24th Place and there’s a 1920s rectory next to the church.)

The parish was a big one and, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society, by the 1920s there were roughly 12,000 members and sometimes as many as 11 worship services on Sunday. English replaced German in the church and school around World War I.

Interestingly, the church is a pilgrimage site for the Schoenstatt Apostolic Movement and each year pilgrims come from around the world to visit.

The movement was founded in Germany by Pallottine priest Father Joseph Kentenich in an old chapel dedicated to St. Michael and based on what he called a "Covenant of Love" with the Virgin Mary.

During World War II, Kententich’s opposition to fascism landed him in Dachau, where he founded two more Schoenstatt branches. But, afterward, opposition to the movement led to Kentenich being dubbed an agitator by some and he was banished to Milwaukee, where he landed at St. Michael’s and held services in the basement of the church, which is adorned with stained glass windows.

By the mid-1960s, Pope Paul VI paved the way for Kentenich’s return to Germany, but the movement continued in the Milwaukee area – there’s a retreat center in Waukesha which has the altar upon which Kentenich preached during his time at St. Michael’s – and Schoenstatt faithful from around the world still revere the Milwaukee church for its connection to the priest.

Meanwhile, in 1970, Father James Groppi was transferred to St. Michael’s in 1970, where he stayed for six years.

Also in 1970, the St. Michael’s school closed and a few years later the building became home to Urban Day School. Currently it houses the Penfield Montessori School.

The building

The Wisconsin Historical Society called St. Michael's, "an excellent example of late 19th century churches. The wall finish is of rockfaced, ashlar limestone. Its design is influenced by the German Gothic as practiced by many of the local architects."

The steeple soars 230 feet above the sidewalk and it was the tallest in Milwaukee for about a year, when it was surpassed by the 250-foot peak at Catholic Church of the Gesu, designed by Henry C. Koch, in whose office both Schnetzky and Liebert had previously worked. Gesu and St. Michael’s remain the two tallest in Milwaukee.

The choice of the limestone facing really ties St. Michael’s to the West Side of Milwaukee, which as it grew – especially in the 1930s and ‘40s, further west – began to have more and more homes, churches and other buildings faced with this stone, often quarried nearby.

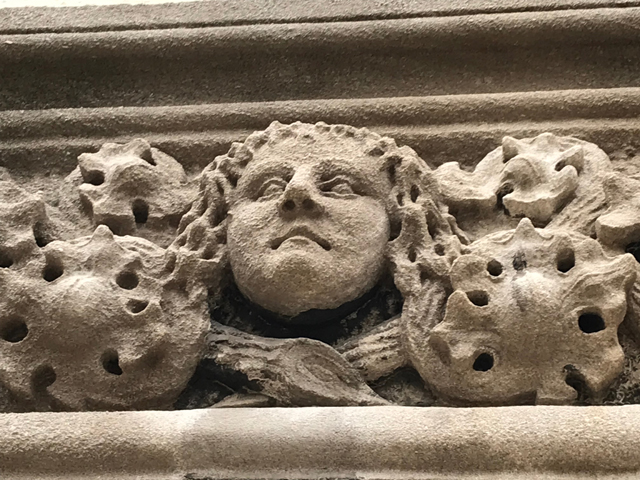

Inside, the cruciform church is a beautiful one, with painted detail – likely the work of Paul N. Klose & Sons, executed in 1924, based on a sign painted just inside a second-story door to the clocktower – and interesting capitals laced with grapes and vines. (When you're outside be sure to check out the grapevines on the facade, too, as well as the faces lurking above the doors.)

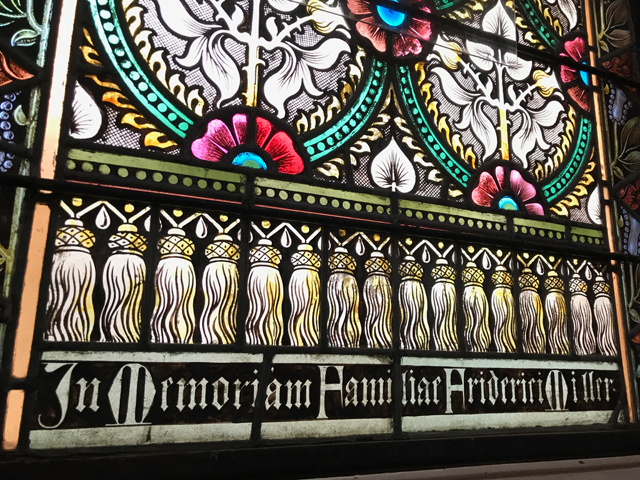

The windows in the nave were made by Tyrolese Art Glass Company in Innsbruck, Austria, and one of them, on the north side of the sanctuary, is dedicated to a Frederick Miller, perhaps of the eponymous brewery not far from here.

The windows, which were beginning to bow, were entirely re-leaded by Enterprise Art Glass a few years ago, thanks to a donation from a parishioner.

Though at the church I heard the imposing wooden altars and screen were shipped from Germany, the Wisconsin Historical Society attributes them to Milwaukee architect Erhard Brielmaier, who did copious work for the Archdiocese, including designed the Basilica of St. Josaphat.

When the altar was, well, altered, the carved wooden communion rail was removed, but was saved and reinstalled at the back of the church along the back of the last row of pews.

These days, a series of flags depicting the many different ethnic groups that worship at St. Michael’s adorn the piers of the sanctuary.

Though the choir loft lacks the gorgeous contour of ones Schnetzky and Liebert installed in some of their churches of the period, St. Michael’s is a beautiful place and if you get a chance to visit, try and get up into the loft not only for a sweeping view of the sanctuary from above but also for a close-up look at that painted border and the grapevines on the capitals.

The organ here is apparently nothing special, though the pipes appear impressive. There is no plate that I could fine attributing the pipes or their case to any specific maker.

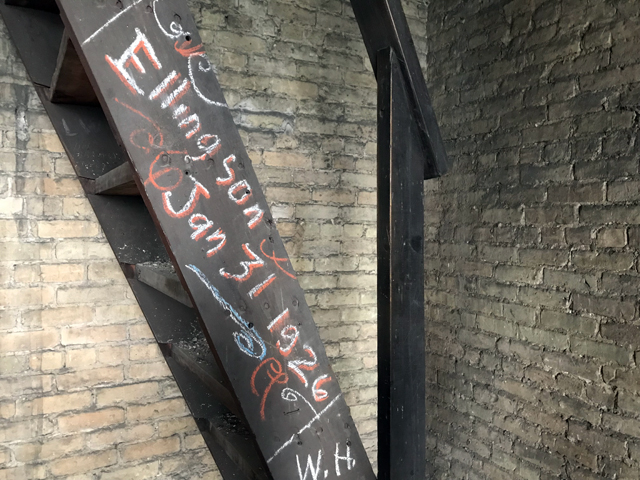

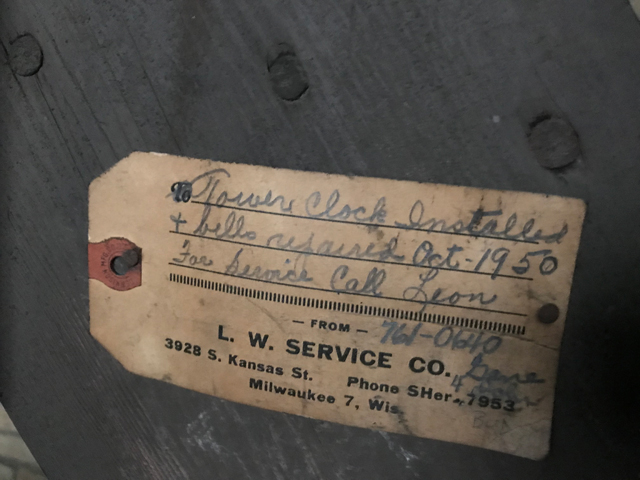

I was lucky enough to get to climb the tower, where there’s amazing graffiti dating back at least to the 1920s and cords to ring the bells – there are four, named 1884, Anna, Maria and Michael – which normally don’t ring anymore, though you can be sure they pealed when I was there!

Making it as far as the top of a steep staircase – almost a ladder, really – I pushed opened the scuttle hatch that accesses the belfry, managing just to spy the bottoms of a couple bells before the flapping of bat wings sent me back down from whence I climbed.

Up here there’s also access to the catwalk above the sanctuary, which offers a close-up view of how these marvels were erected in the days before motorized cranes and other equipment.

A crude ladder built along a rafter high above the top of the sanctuary ceiling below is a reminder of the (hopefully) death-defying work laborers faced on a daily basis back then. Church employees still come up here to change the light bulbs that illuminate the sanctuary.

A changing church

The German community on the West Side has long since dispersed to other parts of the area and their church has changed, though many still come from their "new" neighborhoods to worship at St. Michael’s, which all these decades later, remains an immigrant church, and a place of worship that reflects its neighborhood.

Because of the growth of a Puerto Rican community within the church, Spanish language services were added in 1970. African-Americans also began to come to St. Michael’s to worship and in the 1980s, they were joined by Hmong refugees from Laos. Then groups from Myanmar arrived, too.

Nowadays, the congregation numbers around 1,800 and the church is typically full on Sundays.

"We have a 9 a.m. multilingual mass. We have eight different languages represented; 10 different cultural groups," says Paris Pastor, Rev. Rafael Rodriguez.

"As you can see on the flags," he adds, pointing to the banners that hang above us, "we have the different angels dressed in different typical dress of every culture here."

The church even has choirs that sing in each of the different languages.

"I’m usually seated at the piano and the best thing is looking out and seeing all the different faces," says Barbara Tracey, who has served as director of liturgy and music at St. Michael’s since 1993, "seeing all the different cultures coming together here."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.