LOUISVILLE, Kentucky – There are places and there are PLACES ... spaces that just seem to embrace you and pull you close, or that make your chin drop and your eyes pop: like the glorious Sainte-Chappelle in Paris on a sunny afternoon, or inside Calatrava’s soaring oculus in New York.

For me, one of those places is the more intimate Rathskeller at Louisville’s historic Seelbach Hotel, 500 S. 4th St., which feels simultaneously comforting and astonishing.

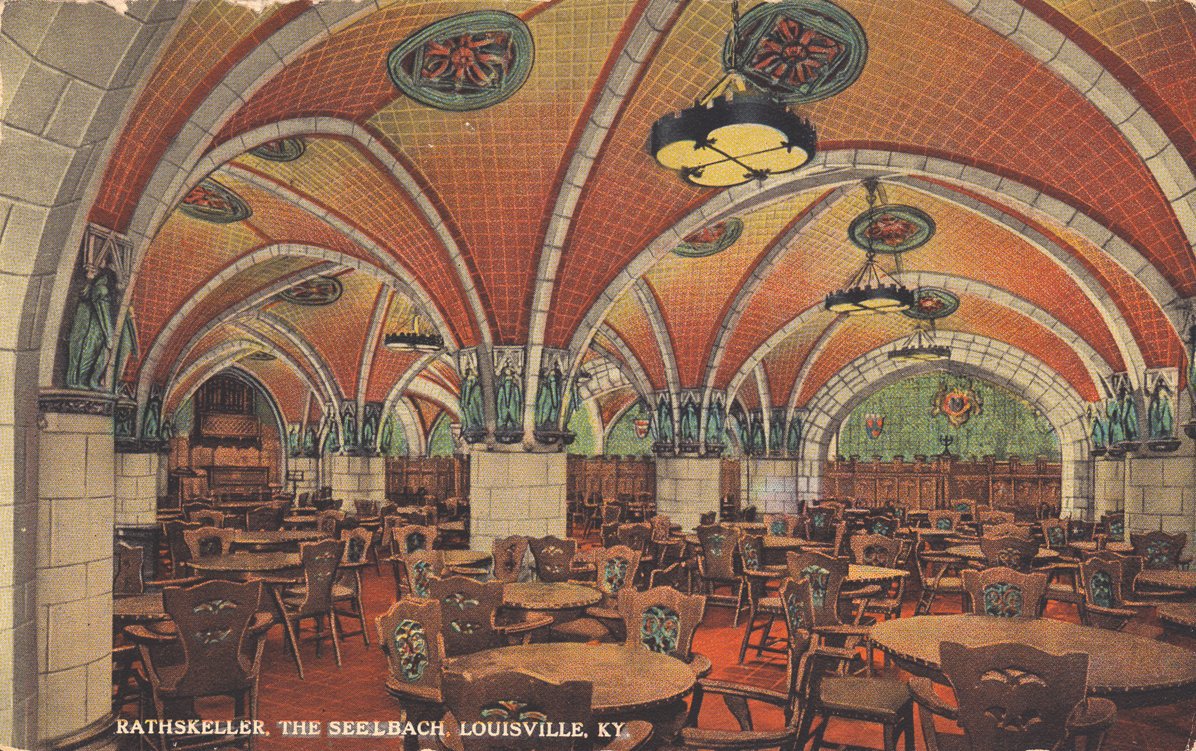

Descending the stairs – nearly hidden behind the lobby’s grand staircase – and entering, you find yourself transported to a German landscape rendered in gorgeous Rookwood Pottery faience tile, with tall and slender – perhaps ominous – pelicans gazing at you from every direction, their wings clamped close to their sides.

The room – used these days only for special events – has a storied past, and if you stand in the center of it and close your eyes, you can almost feel that history come alive.

But, frankly, you don’t have to think about much of anything to bask in the tenebrous space. Just walk around inside and admire the craftsmanship of the Cincinnati-made tile showing Rhenish castles and rolling landscapes, the hand-tooled leather ceiling depicting the signs of the zodiac, the hardwood wainscoting, the lovely stained glass window.

The hotel opened in 1905, built at a cost of just under a million dollars by Bavarian immigrant brothers Louis and Otto Seelbach. Louis had arrived in Louisville in 1869 and five years later opened a restaurant.

In 1891, he helped Otto immigrate, too, and they opened a hotel above the restaurant. Soon, they had visions of grandeur in the form of a hotel that would rival the great hostelries of Europe.

The brothers hired architects Frank Mills Andrews and William J. Dodd to draw them a Beaux Arts palace in the heart of downtown Louisville.

On opening day in 1905, more than 20,000 people showed up to see the new Seelbach Hotel.

A couple years later, the Rathskeller was opened, and drew immediate attention in Louisville and beyond.

"The new rathskeller of the Seelbach Hotel is perhaps the most notable use of decorative tile in this country, if not anywhere," wrote the The Mantel, Tile and Grate Monthly in its January 1908 issue, which paid special attention to the Rookwood clock at the entrance, which had been funded by the Seelbach Realty Co.’s President Charles C. Vogt, as a $10,000 gift.

"The room is low Gothic and the clock is in the quaint old spirit of the 13th century Gothic. The crude elongated figures were made with the thought of the sculpted figures of the Cathedral of Chartres in the mind of the artist, Mr. John D. Wareham: one holds the sun dial, the other the hour glass and around the dial are the signs of the zodiac in low relief. The whole is treated in quiet, low-toned mat glass, greys, grey greens, soft browns and yellows."

The clock is a herald of what’s to come upon entering the main Rathskeller space. The dial echoes the zodiac signs on the leather ceiling, the figures mimic the elongation of the pelicans and the pottery arcade along the top of the clock also ties in.

And the pelicans? Some sources claim they are a symbol of death – which would seem an odd decorative feature in a space like this – while others suggest they’re a symbol of good luck.

The stunning arched room – originally a banquet hall filled with Flemish-style furniture – was an enduring feature of attention for the hotel, too.

It was depicted in postcards by 1910 and in the 1912 edition of Louisville Today, which noted that the decoration cost $40,000 and was based on an actual Rathskeller in a German castle on the Rhine. The space included a drinking fountain that was said to be the largest single piece of pottery fired by Rookwood up to that time.

In 1915, the Industrial Refrigeration trade journal wrote, "The Seelbach Hotel, Louisville, Kentucky, is considered one of the most complete and modern hostelries in America. It is a marvel of the builders’ art, and shows in every line the hand of one who knows the interests of the hotel business.

"A most alluring rathskeller, which the boniface, Louis Seelbach, has provided, is, in a measure, a reproduction of the most famous rathskellers of Germany. The vaulted ceiling, flagged floor and heavy supporting columns, finished in Rookwood tile, give the room a quaint, medieval atmosphere. The design and arrangement has been largely copied by other famous hotels in this country."

And four years later, in its May 3, 1919 issue, The Hotel World: The Hotel and Travelers Journal, wrote, "Another Rookwood Room of the Fort Pitt type (referring to the The Norse Grill Room of Pittsburgh’s Fort Pitt Hotel) is the Rathskeller of the Hotel Seelbach. The wall spaces here requiring decorative treatment were not so large and were easily filled with symbolic devices such as coats of arms, conventional landscapes and castles. The flexibility of the potter’s clay in the hands of the artist modeler, supplemented by the varied palette (influenced) the variety of the results obtainable."

Numerous hotels around the country had Rathskeller-style spaces. In addition to the Fort Pitt, New York's Vanderbilt Hotel had the Della Robbia Room, the Hotel McAlpin in the same city had a tiled grill room and Cincinnati's Hotel Sinton boasted the Grand Cafe, to name but a few.

During World War I, the Rathskeller was transformed into a USO-style club for soldiers at nearby Camp Taylor, including a young F. Scott Fitzgerald, who would go on to feature the Seelbach in his legendary "The Great Gatsby." (Later, the hotel would also appear in the Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason billiards film, "The Hustler.)

Fitzgerald enjoyed himself so much in the Rathskeller that he was tossed out of the place no fewer than three times during his month-long stint at Camp Taylor.

As Prohibition arrived, the Rathskeller became a speakeasy and drew the usual suspects when they were in town.

Al Capone was known to play poker upstairs in the hotel’s Oak Room and to frequent the Rathskeller, too.

According to veteran Seelbach concierge Larry Johnson – who has also written a book on the hotel’s history – Capone would stop at the Seelbach during moonshine runs to Kentucky from Chicago.

"Whenever the police came into the lobby, somebody would step on the button and the doors going into the poker room would automatically close and he would know to get out," Johnson told Wave3 News.

"One of the doors went out and down to the street, and the other door went downstairs to the tunnels underneath the hotel. They would go down into the tunnels and he could go anywhere from a block to a mile away form the hotel without being seen."

Johnson said that Capone appreciated the Rathskeller’s arches, which helped transmit quiet conversations to other parts of the room.

"He liked to try to eavesdrop on the conversation going on around him, and that he was staying ahead of the game," Johnson told Wave3.

There’s a small room adjacent to the Rathskeller that has a stained glass window that opens into the subterranean space. While it looks like it could’ve had a secretive use, Johnson tells me that its life was likely more mundane.

"That was actually the manager of the Rathskeller's office," he says. "He could open up those stained glass windows and watch his people work. There might've been a poker game (in there), but nothing of any importance."

Across the decades, the hotel’s fate and the Rathskeller’s use changed.

"It was a speakeasy in the ‘20s, a beer garden in the ‘30s, a dinner club in the ‘60s, a jazz club in the ‘80s," Johnson says, as we stand in the compact but grandly decorated Seelbach lobby.

However, the survival of that grandeur and of the Rathskeller was anything but assured.

"The hotel was closed from 1975 to ‘82," Johnson says, adding, "there were several changes in ownership.

"The hotel was close to being torn down around 1976, '77. And Roger Davidson, a actor from Louisville, bought it in '78. And between him and Metropolitan Life Insurance, they put $28 million into restoring it. But since '82 when we reopened, we've been taken over, and sold and sold and sold. And the last owners just bought us (in 2017)."

In recent years, the new owners announced a plan to add an 11-story tower to the hotel with a rooftop bar and in March 2021 Kentucky lawmakers approved financial assistance for the project.

These days, the Rathskeller is used as a special event space. It’s a pretty amazing setting for nuptials and parties. After all, it’s likely the last all-Rookwood space of that magnitude that survives anywhere.

Maybe the pelicans really do bring good luck.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.

%20copy.jpg)