In 1921, when the raging epidemic called Packers Fever was in its Petri dish stage, a delirium of equal intensity was caused by a Milwaukee boxer who came within a second of becoming champion of the world 91 years ago this Saturday.

Even few Packers have been as idolized as Richie Mitchell in his time, or gave their fans a bigger thrill than the one Mitchell provided on Jan. 14, 1921.

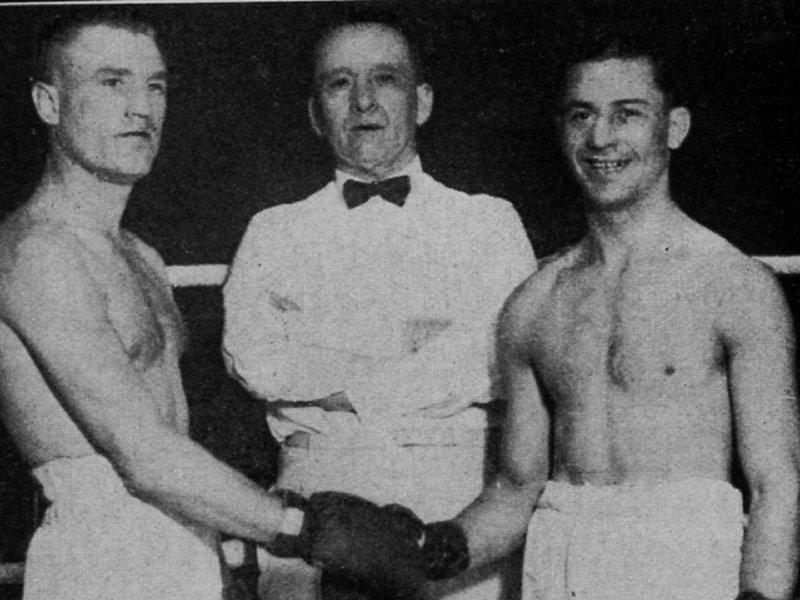

That's when he fought Benny Leonard for Leonard's world lightweight championship at Madison Square Garden in New York, was knocked down three times in a row in the first round and then got up and knocked Leonard down and almost out. The Ring magazine called it "as sensational a first round as the ring has known," and even though Mitchell went on to lose on a sixth round TKO, his incredible courage won him boxing immortality.

The small crowds who attend concerts and plays at the Milwaukee Theater nowadays have never raised the roof there the way Mitchell's fans did when it was the Milwaukee Auditorium and he fought Freddy Welsh, Johnny Kilbane, Benny Leonard and other great mitt stars of that era. Local fans were so crazy about the classy, handsome blond boxer that after Mitchell's 13th pro fight, a victory over Patsy Brannigan on Feb. 24, 1914, they carried him out of the ring and down the street to a restaurant for a celebration.

By the time Mitchell fought Johnny Dundee at the Auditorium on Aug. 30, 1915, it was a ritual of self-anointed "Mitchell Rooters" to parade around town behind a blaring brass band. "If you hear a bunch of noise on Thursday," warned the Journal the day before Mitchell fought Welsh on April 7, 1916, "it will not be anything but the Mitchell followers parading the downtown district."

Lightweight champion Welsh wasn't thrilled when the Rooters held a Mitchell pep rally outside his window at the Pfister Hotel the night before Welsh fought "The Milwaukee Marvel." He was even unhappier the next night when Mitchell clearly outpointed him in 10 rounds at the Auditorium (though Welsh kept his title because it was a no-decision fight. He lost it to Leonard in New York a year later).

Not long after the Welsh fight, Mitchell was watching a movie in a downtown theater when his car was stolen from the street out front. Some avid fans put an ad in the newspaper offering a $50 reward for "information that will lead to the return of Richie Mitchell's 1916 5-passenger Mitchell automobile." For a few days the city was downright unsafe for anyone driving an identical vehicle.

Mitchell joined the U.S. Navy during World War I, and when he left for Fort Sill, Okla., a crowd turned out at the local railroad station to see him off. He wept as he told his fans, "I'm going to do my best, and serve my country to the best of my ability."

More than a thousand people were at the downtown depot when Mitchell left to fight Leonard for the title, and later a chartered train called "The Mitchell Special" carted hundreds of Milwaukee fans to New York City for what The Ring called "the night boxing crossed over from 'the other side of the tracks' – when rugged Tenth Avenue mingled with fashionable Park Avenue, and the Gas House District met up with Newport and the Hamptons. Bankers, brokers and political bigwigs blended with longshoremen, clerks, truck drivers and barbers in one happy gathering." The fight was co-promoted by Tex Rickard and Anne Morgan, daughter of financier J.P. Morgan, to raise money to rebuild France after the Great War.

"I never seed nuthin' like it!" said Rickard, agog at the tuxedoed, begowned crowd at the Garden. Columnist Rube Goldberg of the New York Mail wrote: "It was simply wonderful, that's all. Old case-hardened, leathery-skinned, grimy-bearded sports, who have been going to sports since the aquarium had only one fish, were enthralled and speechless."

Milwaukee fans gathered in front of Morgenroth's saloon on what's now North Plankinton Avenue near West Kilbourn Avenue, to hear reports telegraphed from ringside. They groaned when the news came that Mitchell had been knocked down three times; and when the next report said that Leonard was down, most figured the telegraph operator had gotten mixed up in his excitement.

But it was true. Years later, Leonard would recollect: "I can still see Mitchell, his one eye badly bruised and with a large lump under it; I can see how he wobbled as he came up after his last knockdown and how I motioned for him to come at me for my last punch. Then, suddenly, I recall how from nowhere a punch went through the air, landing on my jaw and sending me to the canvas...

"I was goofy, not only for the rest of the first round but for four rounds after that. Honestly, I did not regain my bearings until the sixth, in which I finally battered Richie so hard that the referee stepped between us and stopped the war."

Boxing Hall of Fame inductee Leonard said more than once, "Always remember to put the name of Richie Mitchell first when listing the great lightweights of my time." After their fight it came out that Leonard had bet Gotham gambler-in-chief Arnold Rothstein $10,000 that he would knock Mitchell out in the first round. But Mitchell's fans blamed his three knockdowns on a "first-round jinx." He was often knocked down in the opening round of important fights, and Journal reporter Sam Levy said the problem was Mitchell's popularity and his desire to please his fans:

"Mitchell has countless friends. These friends have been a worry to him. He enters the ring thinking of his moral supporters. He is in there to satisfy their wishes. Being of a nervous temperament, it has required several rounds for him to get well started. His first round disasters may be attributed to this. He worries too much, and is too anxious to make a flying start so his friends will not be disappointed in him."

Some even suggested that Mitchell's handlers have Richie spar a few rounds in his dressing room before a fight so that when he got in the ring what would be the first round for the other guy would be the fourth or fifth round for him.

In later bouts at the Auditorium, fans stood on the chairs, tossed their hats into the air and screamed themselves hoarse when the bell rang to end the first round with the local hero still on his feet, because "Richie the Lion-Hearted" – another popular Mitchell nickname – had survived the jinx.

Four months after the Leonard fight, when Mitchell stepped into the ring just to work in the corner of a preliminary fighter, the Auditorium crowd gave him a thundering ovation that went on for five minutes. His trainer, Fred Saddy, told me it took Mitchell a half hour to walk two blocks along Wisconsin Avenue downtown because the stores would empty as people rushed out to greet him.

After he died at 53 of a burst appendix on June 26, 1949, Journal sports editor R.G. Lynch wrote, "No one who came to Milwaukee since Mitchell's fighting days can appreciate what an idol he was."

Not many have walked in his footsteps since, though Mitchell's nephews, Jerry and Tommy Shannon, literally did in 1950 when they won local high school boxing titles wearing their famous uncle's boxing shoes.