Reflections of a serial killer

25 years after Jeffrey Dahmer’s first headline

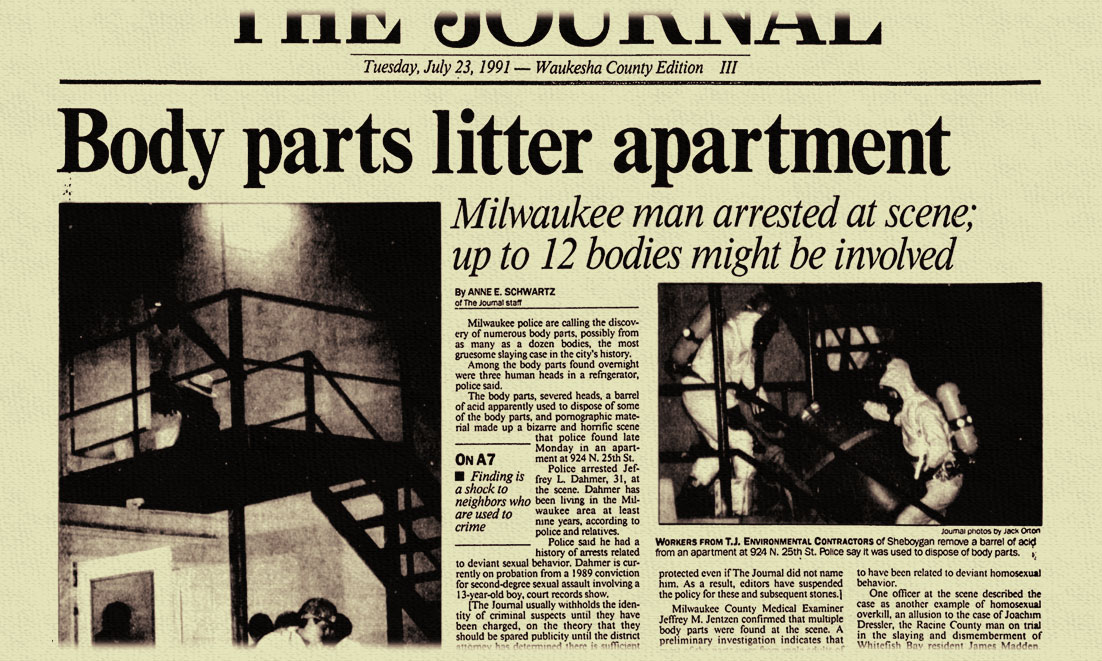

A real estate agent once declared I would never sell my house if I insisted on displaying in the foyer the enormous framed front page of the Milwaukee Journal from July 23, 1991 that welcomed guests to my home with the headline, "Body parts litter apartment," and my sole byline beneath it. Now, 25 years later, it is clear I wasn’t the only one with memories to conceal, or better yet, to discard from that horrible era.

As a parttime crime reporter for the former Milwaukee Journal (and part-time waitress, like every well-paid journalist), I received a tip from a police source just before midnight on July 22, 1991. Two Milwaukee Police Officers had made a gruesome discovery — a man had been keeping body parts in his apartment – including human heads in the refrigerator. That tip led me to an apartment building at North 25th Street & Kilbourn Avenue in Milwaukee. It was a tip that led me to inexorably be linked to one of the most famous serial killers of our time – even 25 years later.

The backstory

Jeffrey Dahmer, 31 when he was arrested in 1991, sexually assaulted, killed and dismembered 17 men and boys – 16 in West Allis and Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and one victim in Ohio – all between 1978 and 1991. His killings involved necrophilia, cannibalism and the preservation of body parts. The stories dominated the local headlines of the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel (Milwaukee was then a two-daily newspaper town) and were soon picked up by national and international media. His trial in 1992 was an event of circus-like proportions.

I covered the trial and wrote a book on the case, "The Man Who Could Not Kill Enough: The Secret Murders of Milwaukee’s Jeffrey Dahmer" — the only book written by a local reporter. There was a morbid curiosity to know the details, but it was more than that – there was a desire for people to read the facts and then to figure out how to ensure this never happened again. There were several so-called "quickie" books, along with a book authored by Dahmer’s father, Lionel Dahmer. There have been a few movies that featured re-enactments of the case with considerable artistic license. (Factoid: movie star Jeremy Renner portrayed Dahmer in one of the films.) There were comic books, trading cards and tasteless jokes, all featuring a city that, prior to 1991, was known for our proud German heritage and as the setting for the TV classic, "Happy Days" and "Laverne and Shirley."

The discovery that a serial killer had lived in our midst in the Milwaukee area for 10 years where he murdered 16 males set the city on its heels and remains a subject into which few want to delve in Milwaukee. I am welcome to discuss my work of 26 years as a crime reporter, and nearly a decade in law enforcement, including the most unsavory case details of crimes that made the headlines, but I am not welcome to discuss the Dahmer case. Not here.

I train law enforcement and prosecutors on communication strategies all over the world, and from Great Britain to Macedonia, during the question and answer portion of my presentation I inevitably have been called upon to answer all manner of questions on the story of Jeffrey Dahmer.

Consider that average age of the current class of police recruits is roughly 21 years old. To provide perspective on some of the biggest news stories in the country, those future police officers were 6 years old on 9/11. They weren’t even born when I broke the story of Milwaukee serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer 25 years ago this week.

Today’s headlines are rife with stories of attacks on police and a community that has drawn a blue line between those who support the police and those who view law enforcement with a skepticism and at its worst and most dangerous, cynicism and hate. As a career observer of law enforcement, I can’t recall a time when negativity toward police was as it is in 2016. But I do recall the climate in Milwaukee in 1991 in the weeks after the Dahmer case became a mainstay of daily news.

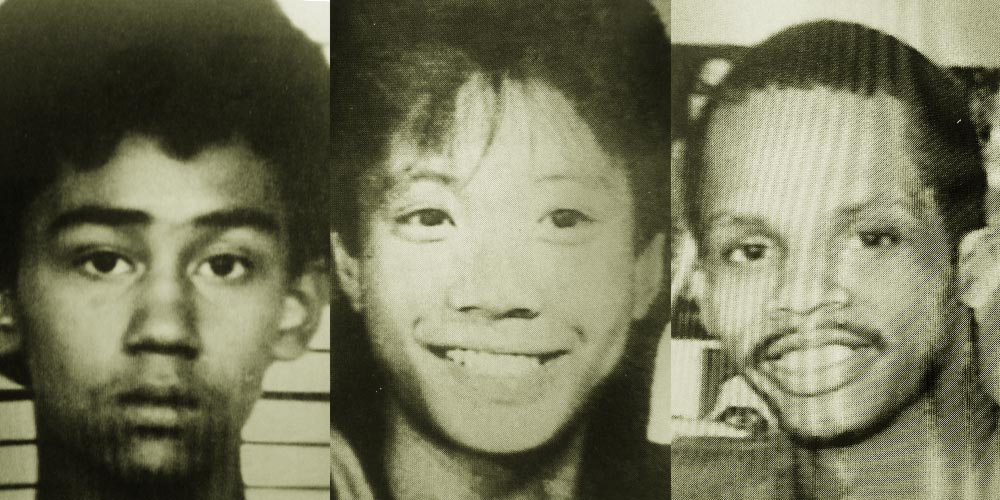

Two months before Dahmer was arrested, two Milwaukee police officers responded to a call in an alley next to Dahmer’s apartment on May 27, 1991 for a report of a "man down," a man who an anonymous caller said was "badly beaten." An ambulance had been sent. Officers Joseph Gabrish and John Balcerzak arrived at the scene to see what appeared to be a young man, naked and dazed wrapped in a blanket with Milwaukee Fire Department paramedics. Jeffrey Dahmer was standing at his side.

What appeared physically to be a young man was actually 14-year-old Konerak Sinthasomphone. Dahmer had met Konerak in the Grand Avenue Mall and offered him money to come home with him and pose for some pictures. He went willingly, as did all Dahmer’s victims. Dahmer took a few photos of Konerak and then the boy was given a drugged beverage. When Konerak passed out Dahmer left to get more beer from a nearby liquor store. With Dahmer gone, Konerak revived somewhat and fled the house, naked.

One of the traits of serial killers is that they are master manipulators – that’s how they often kill undetected for periods of time. Dahmer, a good-looking, well-spoken man, told the officers that Konerak was his 19-year-old houseguest and that he had "had a little too much to drink." Dahmer produced his own photo identification and the officers were satisfied this was a "domestic situation." Just to be sure, the officers escorted Konerak and Dahmer back to Dahmer’s apartment where there were no visible clues that this was a killer’s abattoir. The officers left Konerak with Dahmer. This was Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1991 and a crystal ball is most certainly something that didn’t come as general police issue. It still doesn’t.

Dahmer was caught and arrested on July 22, 1991. He pleaded guilty and was convicted of 15 of the 16 murders he committed in Wisconsin. He unsuccessfully argued that he suffered from a mental disease and was sentenced to 15 terms of life in prison. He was later sentenced to another term of life imprisonment for the first victim he killed in Ohio in 1978. On November 28, 1994, Jeffrey Dahmer was beaten to death by another inmate, Christopher Scarver, at the Columbia Correctional Institution in Portage, WI.

Where are they now?

With the passing of 25 years since serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer’s crimes were exposed, we have an opportunity to take stock of what has come to pass since then in the media, in policing and in the lives of those forever linked to the case.

Media landscape

While writing the acknowledgements in my book, I thought I should probably thank the FedEx guy. He picked up my chapters in the weekly envelope and sent them off to my publisher New York. I practically burned sage over the box in his hands when I sent back the final approved manuscript. This is what officially defines me as a tribal elder in the world of print journalism. No pressing "send" on a computer the size of a notebook – and about as light. No tweeting from the scene "Guys in HAZMAT suits w/blue barrel, fridge. #apartmentofhorrors." No "Googling" to find information on Dahmer’s childhood in Bath, Ohio. Google was founded in 1998. I had to go to Ohio and search for his home, his high school friends, and even his prom date.

The World Wide Web wasn’t available to the public until mid-1991, although home computer use was becoming more common. The first blogging sites became popular around 1999; MySpace and LinkedIn entered the social media scene in the early 2000s and Facebook and Twitter became available worldwide by 2006.

When I say I "broke" the story, young people can’t understand that the details were first revealed seven hours after I arrived as the first reporter on the scene. That simply would not happen today in a world where supposition, rumor and first reports cross millions of cell phone screens within minutes.

Jeffrey Dahmer

Dahmer was sentenced to 16 consecutive life terms. He was incarcerated for two and one-half years at the Columbia Correctional Institution in Portage, Wisconsin before he was beaten to death by a fellow inmate, Christopher Scarver, in November 1994. He was cremated and following a court battle, his ashes were divided between his divorced parents, Lionel Dahmer and Joyce Flint. Dahmer had hoped to write a book and to divide the proceeds among his victims’ families but he never did.

Joyce Flint (Dahmer’s mother)

Joyce Flint moved to California after her divorce from Jeffrey Dahmer’s father, Lionel, in the late 1980s. She first managed a retirement residence before becoming a case manager for the Central Valley AIDS Team in 1991. She worked in the field of HIV and AIDS treatment in the Fresno area until her death from breast cancer in November 2000. Thanks to the generosity of Jeffrey Dahmer’s attorney, Gerald Boyle, Joyce was able to fly to Wisconsin several times to visit her son.

Lionel Dahmer (Dahmer’s father)

Lionel Dahmer still resides in Ohio. He wrote a book about his experience finding out that he had raised a serial killer entitled, "A Father’s Story."

David Dahmer (Dahmer’s brother)

After the case played out in international media, David, Jeffrey Dahmer’s younger brother, changed his name and lives in anonymity.

Officers John Balcerzak and Joseph Gabrish

The two police officers who returned Konerak Sinthasomphone to Dahmer two months before Dahmer’s crimes were discovered were fired by then-Police Chief Philip Arreola in September 1991. The Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission upheld the firings in November 1992, finding that the officers were guilty of gross negligence. The officers appealed and were ordered reinstated to the Milwaukee Police Department with back pay in April 1994 by Reserve Judge Robert Parins, who said their dismissals were "shocking to one’s sense of fairness." He acknowledged the officers had made mistakes but that it was unfair to judge them in hindsight.

Dahmer’s defense attorney, Gerald Boyle, agreed. "The second-guessers of this world wanted to hold those two officers responsible for what Dahmer did," Boyle told me this week. "And there is just no way you can say that."

Gabrish was hired by the village of Grafton, Wisconsin, as a police officer in 1993 and he did not return to the MPD. He has since been promoted to the rank of Captain and is second in command of the department. Additionally, he serves as the Chief of Police for the Town of Trenton in Wisconsin, an appointment he accepted because of his continued passion for policing and its importance to the community.

In a 1991 interview with the Milwaukee Journal, Gabrish said, "We're trained to be observant and spot things. There was just nothing that stood out, or we would have seen it. I've been doing this for a while, and usually if something stands out, you'll spot it. There just wasn't anything there."

Balcerzak continues to serve as a Milwaukee Police Officer. He was elected as president of the Milwaukee Police Association, the police union, from 2005-2009.

Philip Arreola (former Milwaukee Police Chief)

Arreola left Milwaukee in 1996 to become Chief of Police of the Tacoma, Washington, Police Department. He stepped down from that post in 1998. He most recently served as regional director for the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service in Denver, Colorado. He has returned to Milwaukee every year to attend the Wisconsin Hispanic Chamber of Commerce gala where a scholarship is awarded in his name.

Gerald Boyle (Dahmer’s defense attorney)

Boyle continues in the practice of law in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with "no intention of retiring," he told me this week as we discussed the 25-year mark of the case – the biggest in Boyle’s career.

Even after Dahmer was incarcerated and his father had retained other counsel, Boyle continued to visit with Dahmer privately. While some had cried out for Dahmer to be sent to prison, Boyle feels strongly to this day that Dahmer belonged in the Mendota Mental Health Institute, a Madison, Wisconsin psychiatric hospital, where he could be studied. "God knows what we could have learned," Boyle told me. "If we could have gotten him to Mendota, we might have found out about how to help all these other adolescents with mental health problems who are committing terrible crimes."

Tracy Edwards (Dahmer’s would-be 18th victim who led police to the killer)

Once hailed as the "hero" of the Dahmer discovery for leading police to killer’s apartment after he escaped, Edwards’ life took a violent turn – this time with him as the suspect.

Within a year after Edwards’ escape - and the fame and cash that he sought discussing it – he was arrested after appearing on a national talk show when police in Mississippi saw him not as a survivor, but as a suspect they sought in connection with the sexual assault of a 14-year-old girl there.

In 2011, nearly 20 years to the day he escaped Dahmer, the homeless Edwards was arrested for helping another homeless man throw a third off a Milwaukee bridge to his death. He served one and a half years in prison for his role in the crime. He is no longer on state supervision, and at last reports, remains homeless in Milwaukee.

Christopher Scarver (inmate who killed Dahmer in prison)

Scarver already was in prison for killing another man when he killed Dahmer and inmate Jesse Anderson while the two were cleaning a bathroom at Columbia Correctional Institution in 1994. Anderson was serving time for the murder of his wife after he stabbed her to death in Milwaukee’s Northridge Mall parking lot, telling police "two black guys did it." It was later determined that Anderson made up the story.

Scarver is now serving two life terms at a Colorado federal prison where he provided a jailhouse interview to a New York Post reporter in 2015. Scarver’s account of Dahmer’s prison behavior is at odds with those who knew Dahmer’s prison demeanor well and had kept in contact with him.

A governor’s commission, which included Boyle, determined that corrections officers at Columbia were not at fault in the events that led to the two inmates’ deaths. As a part of his work for the commission, Boyle met with Scarver and none of the narrative Scarver provided in his story to the New York Post was ever mentioned.

Other players

There were other players involved in the case of Jeffrey Dahmer who have since died:

Glenda Cleveland, Dahmer’s neighbor who notified police that her daughter saw a naked young man in the alley, died in 2010;

Patrick Kennedy, the Milwaukee police detective who together with his partner, Dennis Murphy, befriended Dahmer and skillfully extracted Dahmer’s confession over the days and weeks following his arrest, died in 2013. Dahmer confessed to murders that might never have been discovered but for his comfort level and desire to share every detail with those two detectives.

Milwaukee real estate developer and millionaire Joseph Zilber died in 2010. Zilber was appalled when he heard that Dahmer’s personal property was to be sold. Zilber raised $407,225 — mostly his own money — to buy Dahmer’s possessions and had the lot of it hauled away before dawn to be destroyed in an Illinois landfill. The money went to the families of Dahmer’s victims.

The Oxford Apartment building at 924 N. 25th Street where Dahmer lived and committed 12 of the murders, was razed in November 1992. The property remains overgrown and surrounded by a tall, rusted chain link fence. Efforts to morph the property into everything from a memorial to a playground have failed.

"Cream City Cannibal Walking Tour"

While many in Milwaukee don’t relish the idea of keeping the Dahmer story alive – admittedly even for a 25-year retrospective – some have tried to monetize it.

One company proposes for $25 to give takers a "walk in the footsteps of the predator" on "the exact streets where cannibalistic serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer picked up" his victims. Groupon banned the tour from advertising to its users.

The area of South 2nd Street, formerly a haven for gay bars, bathhouses, and not much else has experienced a resurgence as a district for diverse entertainment venues, craft beer breweries and tony restaurants. Known as Walker’s Point, it is a destination for all the positive reasons business owners there hope for.

Adam Walsh connection

In 2015, one book author posed a theory that Dahmer was responsible for kidnapping and killing 6-year-old Adam Walsh in 1981. Those who studied the serial killer, those who knew him and even Adam’s father, John Walsh himself, have debunked the idea. In December 2008, police named Ottis Toole as the boy’s killer.

Ambrosia Chocolate Factory

The chocolate factory received unwanted attention as Dahmer’s workplace. Dahmer revealed to investigators that he had kept a skull in his locker there as a keepsake of one of his murders. In 1992, Ambrosia moved its operations to another location in Milwaukee for reasons unrelated to the case.

Room for rent

In April 2016, a website for rental properties during the Republican National Convention turned up an unlikely offering – Dahmer’s childhood home in Bath, Ohio where he killed his first victim in 1978. For $8,000, interested parties could rent the three-bedroom, two-bath property during the RNC when housing could be hard to come by. No returned calls to the query about whether the house had any takers for last week’s festivities.