Though we may often think of Eschweiler-designed buildings as the red brick buildings the firm designed for what is now UW-Milwaukee and the agricultural school out on the County Grounds (which later came to be called "The Eschweiler buildings"), the firm of Eschweiler & Eschweiler, by the 1930s, was drawing some fine Art Deco buildings in Milwaukee, too.

One thinks of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass enamel plant in Walker’s Point, of the original Gaenslen School in Riverwest, of Philipp Elementary in the Rufus King neighborhood, of the Mariner Building that currently houses Hotel Metro.

One of the best surviving examples of Eschweiler-drawn Moderne is Radio City, 720 E. Capitol Dr., the home of WTMJ television and radio stations and WKTI-FM.

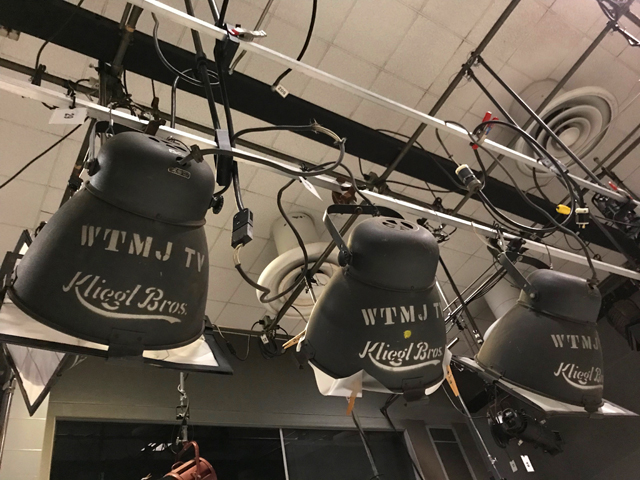

The building was begun in 1941 as a new home for WTMJ radio, which had been broadcasting out of the Milwaukee Journal building on 4th and State since it went on the air in 1927.

The WTMJ television station was launched in the new building – which claims to be the first to be purpose-built as both a radio and television studio – in December 1947 and it is currently celebrating its 70th anniversary.

In honor of that landmark birthday, Kent Aschenbrenner, the senior director of engineering for E.W. Scripps Co., which owns the station, invited me over to take a look.

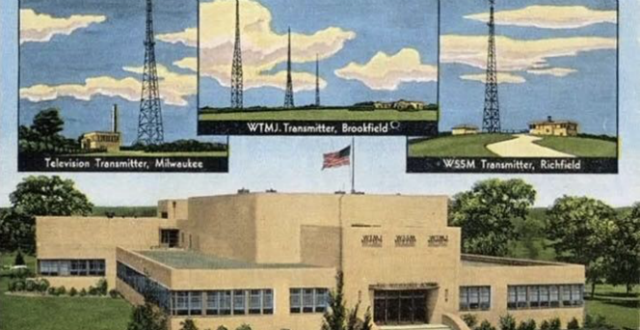

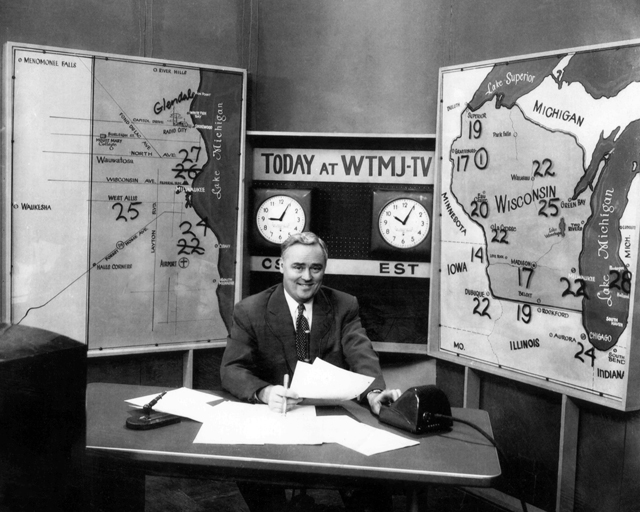

(PHOTO: Old Milwaukee Facebook)

I’ve always been enamored of the exterior of the place, with its central pavilion and emanating wings, its smooth walls, rounded corners (isn’t that an oxymoron?). There was an addition around the back in 1966 and another to the west in 1989.

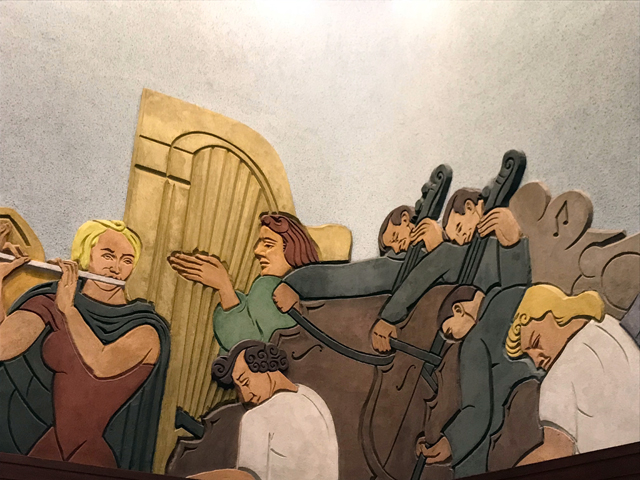

Stepping inside the lobby, one can’t help but notice the themed sgraffito (colored and etched plaster) murals on the upper parts of all four walls.

On the north wall, a large female figure with her arms open is meant to conjure broadcasting. To the left, a group of musicians performs on one side, depicting "sound," and to the right other figures represent dance and theater and represent television. The fourth panel, above the entrance, represents the audience receiving the signals from radio and television.

The works were created by Jefferson E. Greer, a Milwaukee-based artist – born in Texas in 1905 – that worked in a variety of media, including plaster and watercolor. Greer – who studied at the Layton School of Art and worked and taught in Milwaukee for a decade beginning in 1932 – did WPA work and was among a group of artists that created murals at post offices around Wisconsin in the 1930s.

Greer’s plaster relief mural, titled "Discovery of the Northern Waters of the Mississippi," was created for Prairie du Chien in 1938. But during the 1930s, for four months of each year, Greer would head out west to do his work as a pointer, transferring measurements from an artistic model to the side of a mountain, dangling from a rope 600 feet above the ground.

Greer was working to carve the faces of Washington and Roosevelt (and maybe Jefferson and Lincoln, too) on Mount Rushmore.

In 1941, Greer began work on the the WTMJ murals. According to a contemporary newspaper report, Greer spent six months on preparatory designs and 20 days doing the actual mural, which entailed a time-is-of-the-essence mix of carving and modeling with chisels and sharp knives.

"Greer is one of only a few artists now working in this medium, the revival of an art which goes back to the Renaissance, and in which he did an immense amount of research," according to the Journal.

"He explains that the basis of this art is color, with no attempt to imitate form literally, but rather to create planes so that they catch the light and give the impression of form. The murals tell an abstract story, based on broadcasting through sound and television. However, Greer says that their story telling quality is secondary to architectural decoration – in other words, at first viewing, you are supposed to enjoy their soft, earthy colors and rhythmic qualities before trying to read their story.

"Greer said it was his desire to show how the outflowing waves of radio bring education and entertainment to all people – to the crowded cities, the farm and even to the wilderness."

Inside, I meet Aschenbrenner and our mutual friend Rachael Glaszcz, a special projects producer at the station, and I can’t help but stop constantly to check out Art Deco bubblers, brass handrails and other details. Historical photos of the place line the walls, which also slows me down.

Aschenbrenner tells me about Radio City and his connection to it.

‘About 1941, the Journal wanted to build a facility to house the radio station, which was in existence from 1927 onward and get into the new technology of television, so this was started," he says. "The war came along, and halted the progression of television, because the tubes and some of the equipment needed for television was put into the war effort.

(PHOTOS: Courtesy of WTMJ-TV)

"We're standing in the original building right now," he says as we stop to look at some of those old photos. "If you look at the original building from a bird's eye view, it's symmetrical – one side was TV, one side was radio. The middle part here is where the auditorium was. There were a lot of radio shows, then eventually television shows out there (on the stage). I think there were 350 seats in the auditorium there."

The auditorium is now gone, replaced by radio studios and production rooms, as well as a radio newsroom and other spaces, but traces of it remain. When the auditorium was divided up into these spaces – around the time the ‘89 addition was built – the new rooms got dropped ceilings.

But upstairs, through a door, Aschenbrenner takes us out onto the structure that holds up those ceilings and we can see the top of the old stage, the decorative plaster ceiling and the top portion of the proscenium. Across the room, we can see the old booth that was opposite the stage.

Aschenbrenner knows this place inside and out. And he should, because he’s been there a long time.

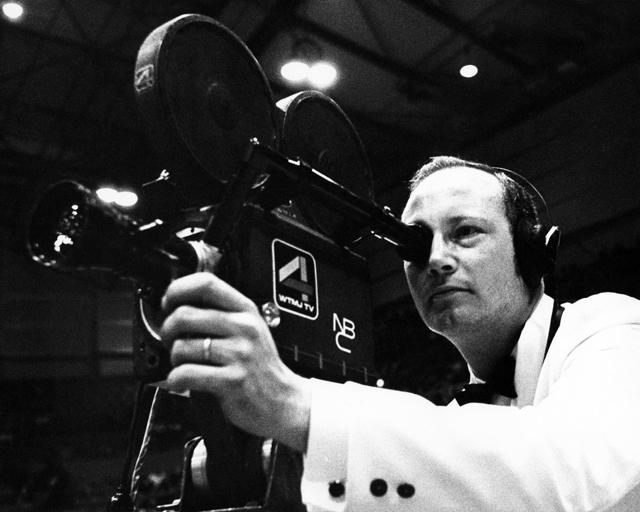

"I started in April of ‘77," he recalls. "I just was in my final semester at Milwaukee Area Technical College. They had a program there for electrical technology communications and we all were looking to get a job in broadcasting. And back then you needed a first class radiotelephone license to work in a facility and work with transmitters.

"I started working on the news studio crew with (on-air talent) John McCullough and Paul Joseph and Hank Stoddard. (We were) wearing lab coats (pictured above), and there were probably 45, 50 engineers here working maintenance and supporting the radio and TV facilities. I started out in news production, so camera.

"It's where everybody started. And then you advanced on to audio for news or switching or what's called camera control to adjust the light levels and colors and all of that stuff. I went to school for electronics and I was more intrigued by the guys who were in maintenance fixing the stuff. So in between news shows I would hang out with the maintenance guys and one guy took me under his wing, George Kasdorf, who was here December 1947 when they put the station on the air. He's still alive today. He took me under his wing and taught me troubleshooting skills and maintenance and so I spent probably 16, 18 years maintaining equipment."

Aschenbrenner rose through the ranks and now, in addition, to running Radio City, he oversees 34 Scripps-owned radio stations across the country.

As we walk around the building, it becomes quite clear that Aschenbrenner is intimately involved with the place. When he lifts us a floor panel to show us a complex web of dozens and dozens of color-coded cable, he tells us about the years he spent cleaning out these cable runs, pulling up old unused stuff and running new wires.

He shows us Studio D, where television went live in Milwaukee and where the classic newscasts were always hosted. It’s where he got his start as a cameraman. He shows us the tiny storage room behind the room where Reitman and Mueller had their studio (pictured below).

We nose around in tape and film archive areas and he remembers working on the stories noted on the tape boxes. In a room full of moribund technology awaiting recycling, he knows the brands and model numbers of the equipment and you suspect that he could tell you more than you’d ever want to know about the capacitors and resistors that made them tick.

We take the tunnel over to the transmitter building – where I get a dramatic look at the cables running out through the wall and over to the soaring tower just to the east – and Aschenbrenner shows me some equipment that’s been sitting in the racks since before he started there in 1977.

It’s a fascinating and humbling experience to meet someone so deeply invested in and knowledgeable about their craft.

But, fortunately, Aschenbrenner isn’t a dull tech-head. He takes the time to show us the crawl space in an unexcavated area beneath the building and tell us funny stories about the wild west days long ago.

He shows us the weird old shower – complete with an extra pair of jeans hanging on a hook nearby – in the basement.

Aschenbrenner knows what each room was used for in its previous incarnation and, in some cases, in a previous previous incarnation. A lot of spaces have gone through changes because over the past 70 years, the business has changed dramatically.

"When I wore that blue lab coat," Aschenbrenner says, "the news was shooting in 16 millimeter film. We had a photo lab downstairs where we had somebody developing film. And they would run it up. (For) the really late breaking news, the film would still be dripping from the chemicals.

"We started getting the electronic cameras that we could record to three-quarter-inch tape probably ‘79, ‘80. And then we went through a number of formats of videotape and now to where we are where you have a card in the camera and electronically send it back.

"A lot of changes. From tube-based equipment to solid state and now everything's computers. We do not have a tape machine in the technical area of the plant. If you were to take a picture walking into the studio in 1977 to today, the light levels are significantly lower because the camera technology is so much better. Back then you had to pour on the lights. There were people standing behind the cameras. Now it's all robotically controlled.

"(Weatherman) Paul Joseph would write on a big plexiglass board with markers and (now there are) the computer graphic systems that you have today. More and more, automated functions are doing these tasks or those tasks."

That really hits home when we stop in the WKTI studio, which is broadcasting, but there’s no one around. It’s on auto-pilot. Though it bears saying that the music is programmed locally, here in Milwaukee, according to local tastes.

There are more people on hand when we stop in to watch the taping of a segment for "The Morning Blend." Host Molly Fay is interviewing a chef and there is a producer, a director and a staffer running the teleprompter. But that’s all.

"It's a tough business to be in," says Aschenbrenner. "Forty years ago if you wanted to watch local news it was channel 4, channel 6, channel 12 and there was not even a 58. Now the consumer has so many more options. That affects revenue and therefore it demands that we do things more efficiently here. Where you had three people standing behind the camera, now two of those are gone because only one person drives all the cameras."

I ask Aschenbrenner is he sees a time in the future when there’s almost no one here running Radio City.

"It's an evolutionary process and, but it's always looking for ways to take care of processes that can be automated," he says. "But there's a lot that still require that human touch and that contribution, the news editors and all of those folks that have to create that story in a very short amount of time and just you know, you’ve got to have human eyeballs."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.