As massive as the former Pritzlaff Hardware Co. complex, 305-333 N. Plankinton Ave., on the corner of Plankinton and St. Paul, seems now, consider the fact that just six of the 16 buildings currently survive.

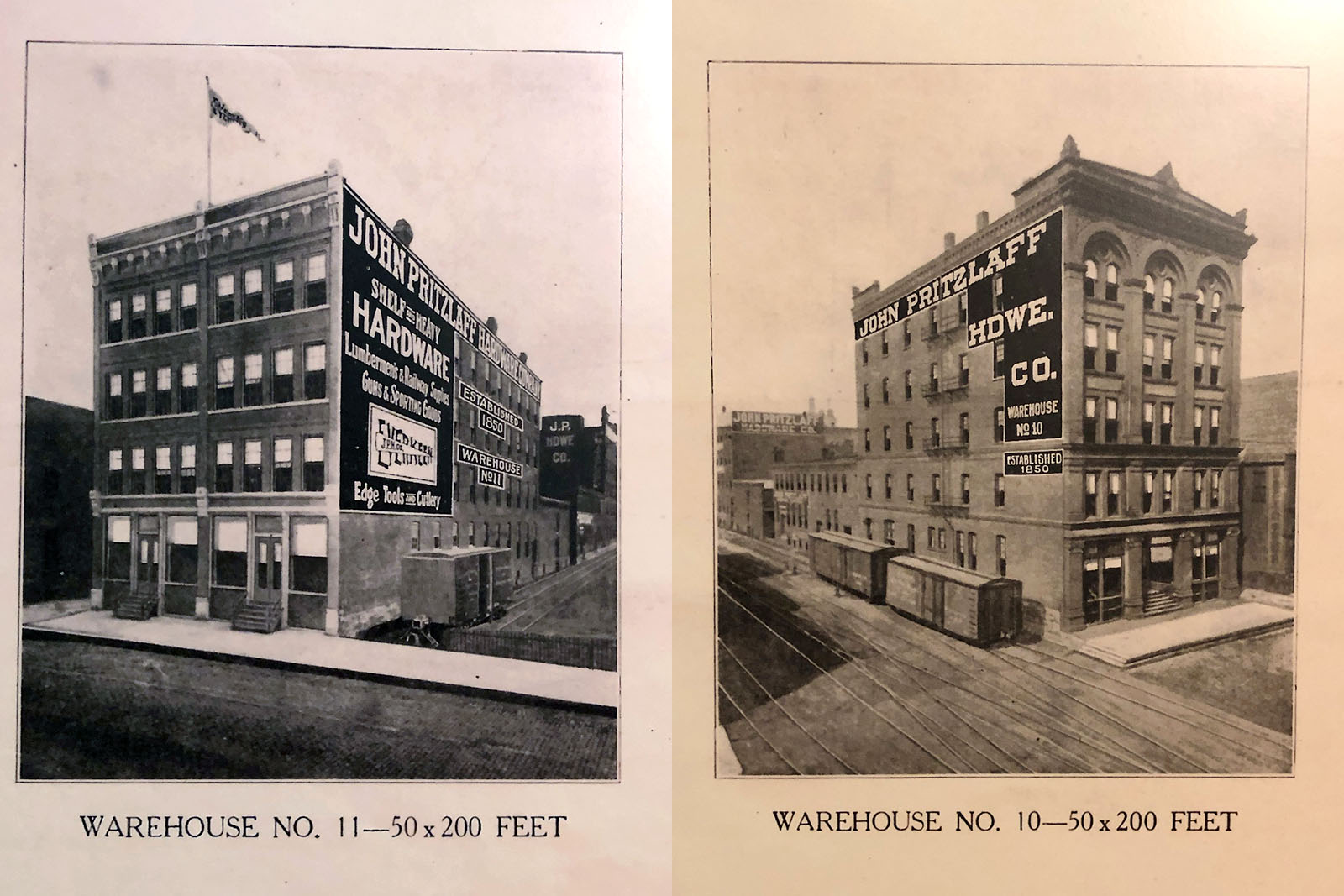

In fact, a century ago, Pritzlaff’s buildings also stood across St. Paul, flanking both sides of Plankinton Avenue.

At the dawn of the 1930s, the company – for a time the largest hardware dealer in the whole of the region – had nearly 500 employees working in its mini city in the heart of Downtown Milwaukee.

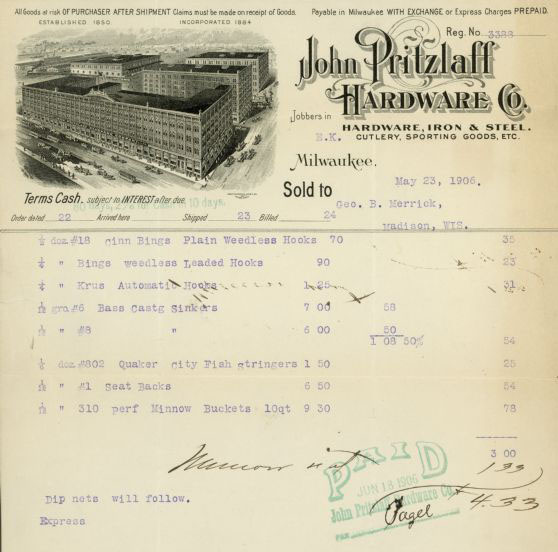

In its day, Pritzlaff sold just about everything, from stoves to sewing machines, coffee grinders, iron, toys and more to wholesale accounts and via catalogs.

The company’s catalog of available items was itself dense enough and large enough to almost be a construction material in itself.

But even the mighty can fall and Pritzlaff closed in 1958, replaced on the site by Hack’s Furniture, which closed in 1984, leaving the complex largely moribund for years.

But about a decade later, developers began to take interest in the site and, finally, Sunset Investors' Kendall Breunig bought the complex in 2005 and began exploring ideas for bringing its six buildings back to life.

Now, there are event spaces, offices, retail businesses, co-working spaces and nearly 100 apartments in the buildings, which – thanks to Breunig’s love of history – are still full of interesting details and many objects owned and/or sold by Pritzlaff Hardware Co.

Soon, local restaurateur Richard Kerhin opens a new eatery called Aperitivo, in the complex. (Check the website for updates.)

A little history

John Pritzlaff was born in Pomerania, in Prussia, on March 6, 1820. He arrived in America in 1839 and came to Milwaukee in 1841, where he worked as a teamster, a sawyer at Schlitz Park and as a cook in the galley of a merchant schooner. In 1843, he took a job with Shepardson & Farwell hardware, where he learned the business while working as a porter.

Portraits of Sophie and John Pritzlaff.

In 1850, he opened his own John Pritzlaff & Co. shop at 1037 N. 3rd St. with August Suelflohn and silent partner Henry Nazro (who had purchased Shepardson & Farwell during Pritzlaff’s time there), and business was so good that they built a new three-story place on the street in 1860-61 (a fourth floor was added to the building, which is now home to Oak Barrel, around 1890).

In 1853 Pritzlaff bought out Suelflohn and in 1866 Nazro withdrew, leaving Pritzlaff as sole proprietor of a large and rapidly growing business.

The hardware business continued to boom and even the new place proved unable to keep up, so Pritzlaff erected the first part of the current complex on Plankinton Avenue in 1875.

It’s easy to spot this part from the street. It’s the section with the name Pritzlaff and the date 1875 near the top, finials marking the endpoints of that original building, designed by John Rugee.

Born in Lubeck, Germany in 1827, Rugee came to America with his family in 1840, settling first in upstate New York and, in 1851, following his father to Milwaukee.

Working in construction supervising the erection of grain elevators and bridges for Stoddard Martin, Rugee entered into partnership with his boss adding architecture and the manufacture of sashes, doors and blinds to their construction work. In 1865, after Martin's death, Rugee partnered with Emil Durr, wholesaling and retailing lumber and shingles, all the while growing his reputation as an architect.

By the time, he was tapped by Pritzlaff, Rugee had worked on buildings for Best, Falk and Schlitz Brewing Companies.

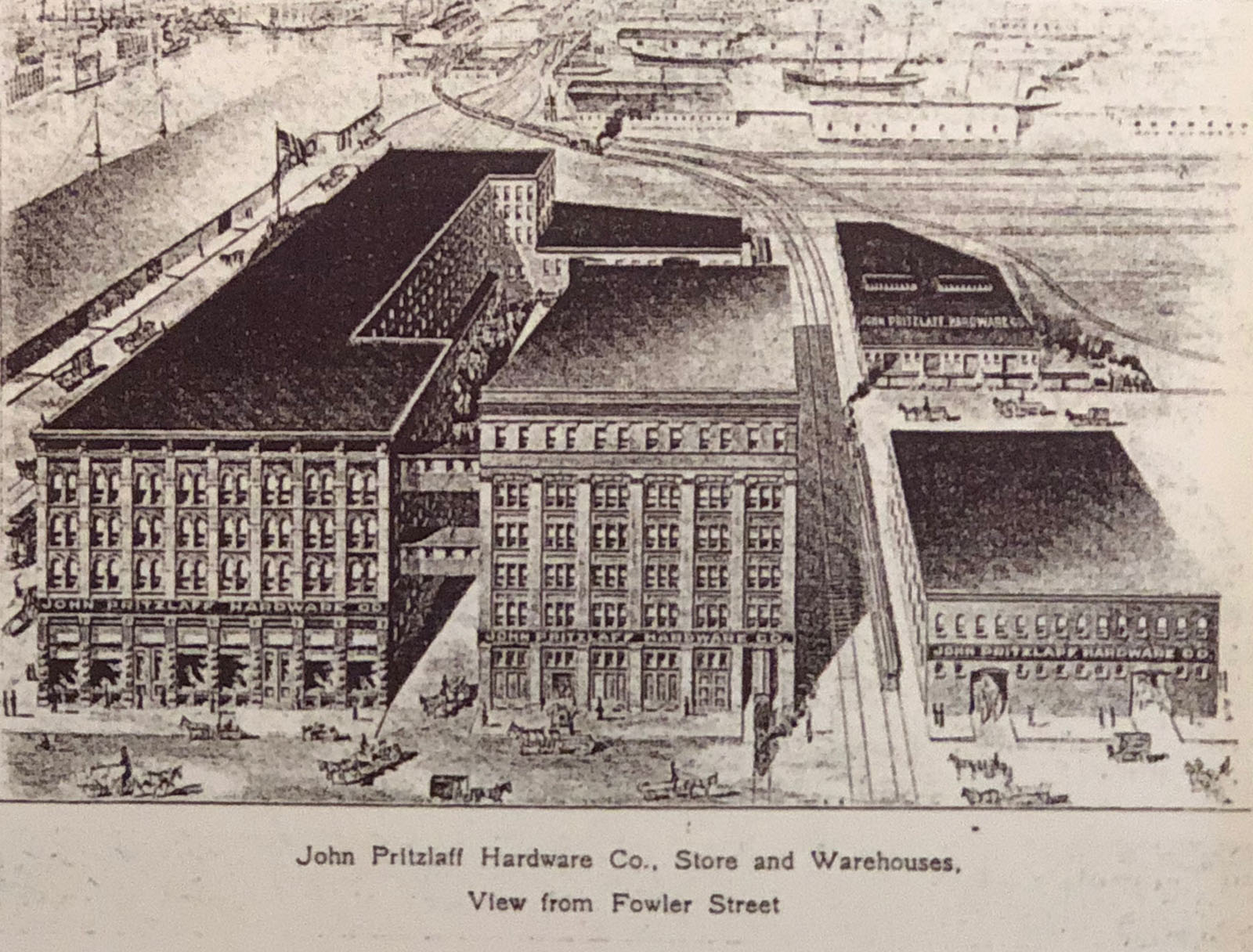

The complex in 1899 (above). (PHOTO: Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

Below, a view dating to 1907.

"The site was advantageous," noted the application for the property's addition to the National Register. "It was situated across the street from railroad freight houses and boat docks on the Milwaukee River, as well as adjoining the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad spur in the process of being built to their new depot."

In the new location, the business continued to expand. In 1881, Pritzlaff had 52 employees and in 1900, 250 worked there. In the second half of the 1870s, Pritzlaff – a devout Lutheran – donated the land on 9th and Highland for the construction of Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church, of which he was a founder and trustee.

In the 1880s, Pritzlaff and his son-in-law (and future mayor) John C. Koch donated land on 24th Place and McKinley Avenue for the construction of Bethlehem Lutheran Church, too.

An 1878 Milwaukee Sentinel article offers a peek inside:

"The basement, which is light and airy, contains all the heavy stock, such as Zug & Co.’s sable nails from Pittsburgh, Pa., chains. Burden’s horse shoes and most of the materials in bulk incidental to this business. The first floor is divided into elegant offices and shipping department, and contains a great deal of stock in the shape of merchant iron and steel in bars, rounds and squares, nails, portable scales of various makes. Black Diamond steel, shelf hardware, and a full line of tin in bulk and tinners’ tools, and other commodities too numerous to mention. The second floor is devoted to a large stock of shelf hardware ... pressed tinware and iron-clad milk cans is an important feature in this section. One part of this floor is divided off into a special show or sample room, and most of the choice goods in the way of builders’ hardware, files, etc., are tastefully displayed on the stands. The third floor brings to view a large stock of rivets, machine bolts of every description, coach and other screws, spades, shovels, carriage and wagon springs, axles and other carriage materials, bellows, sledges, vises and blacksmiths’ tools generally, mice, rat and other vermin traps, wire of every description, telegraph, annealed copper, brass and plated, malleable iron castings of every description. On the fourth floor are found farm implements, T and other hinges, galvanized sheet-iron and other things too numerous to mention."

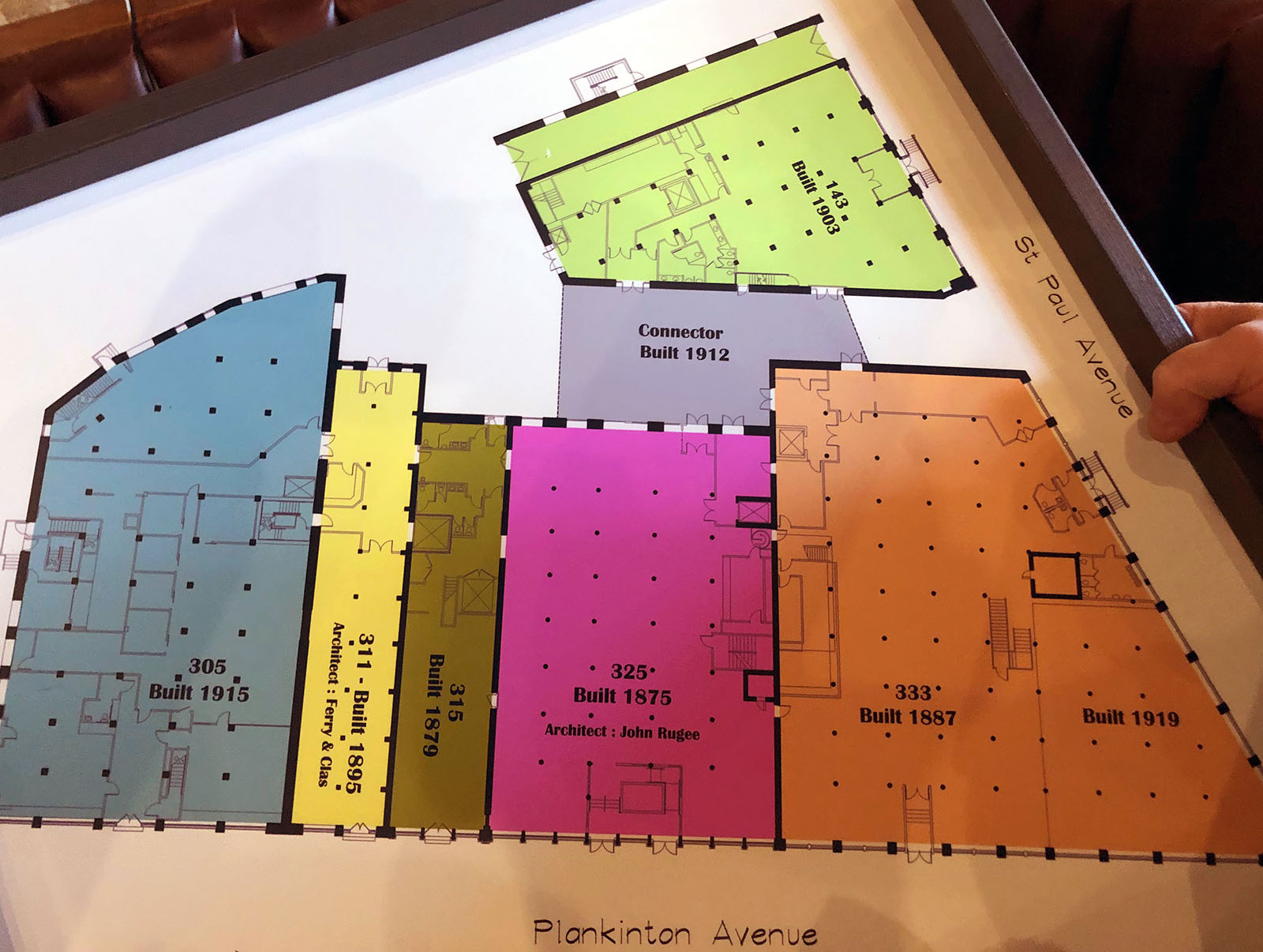

In the current complex, a small section to the south was added in 1879 and a much larger addition to the north followed in 1885. A long, narrow Ferry & Clas-designed addition to the south was added in 1895 and the building to the west, facing St. Paul Avenue, was put up in 1903.

The southernmost part of what we see today was erected in 1915 – three years after a connector joined the 1903 addition to the 1875 and 1887 buildings – and, finally, in 1919, a corner tavern was razed to make room for the final addition, which is at the point where St. Paul meets Plankinton.

The 1915 and 1919 additions were the work of architects Klug & Smith.

"Architecturally, its original 1875 building is an excellent and highly intact example of Italianate style commercial architecture," notes the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Architectural Inventory.

"Possessing characteristic features including a bracketed cornice and impressive brick window surrounds, the building is further embellished with a segmental, open bed pediment with date, dentils, carved stone trim, ornamental cast iron urns and company name in raised lettering. Constructed over a period of 44 years, the facility is also notable for its unique collection of storefront design with examples of decorative cast iron and carved stone columns."

Pritzlaff was located in what became something of a local hardware wholesaling hot spot, with Frankfurth Hardware located two blocks north on Plankinton, the Wholesale Hardware, Iron and Steel Company next door to Pritzlaff, to the south, and a block west on 2nd Street, John's old partner's company, Suelflohn & Seefeld Company.

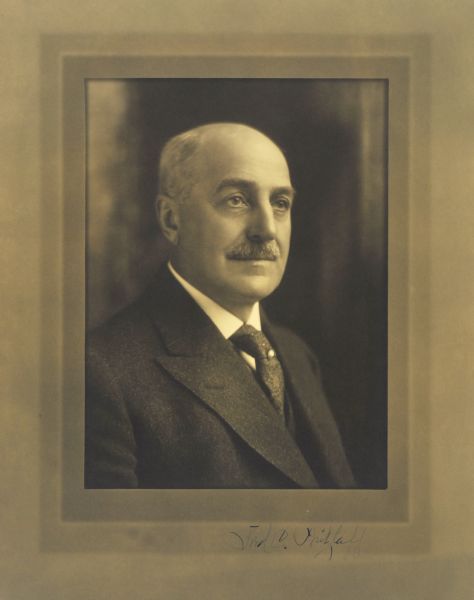

In 1900, Pritzlaff died – leaving behind a fortune estimated at between $500,000 and $1 million (or as much as $30.6 million when adjusted for inflation) – and his son Fred assumed control of the company, continuing to grow it until his own death in 1951.

Like his father, Fred (seen above in a 1921 photo, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society) was active in Lutheran philanthropy, and he also served on the boards of numerous familiar institutions, including First Wisconsin National Bank, Concordia College, the Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church and Northwestern Mutual Life, among numerous others.

In 1952, Fred’s son Edward became president of the company, serving almost until it closed six years later, and was also active outside the family business, serving as president of the National Hardware Association and on the boards of Concordia College, the War Memorial and First Wisconsin.

A 1950s-era photo. (PHOTO: The Pritzlaff Building)

In May 1958, the business was sold to Chicago’s Morrie Chaitlen for $1.7 million. A month earlier, Edward Pritzlaff had announced that the company was getting out of the general retail hardware business in order to focus its efforts on its industrial supply and floor-covering operations.

By mid-July, most everyone at the top had resigned or been fired – some of them going off to start their own businesses to fill gaps left by Pritzlaff’s scaling back – and though Chaitlen was tight-lipped about his plans, newspapers recalled that he’d purchased the Wisconsin Chair Co. of Port Washington five years previous and liquidated it in 1954.

On July 30, Boston Store announced that it had purchased Pritzlaff’s inventory of items like garden tools, cookware and cutlery, barbecue grills and other consumer goods. Liquidation ads following in August and by October, the Pritzlaff buildings were listed for sale.

Just like that, an astronomically successful 110-year-old business was gone.

According to Breunig, part of the problem for the company was that its great railroad advantage – train cars could practically pull right into the buildings – and riverfront location became moot as trucks replaced rail and rivers as main modes of transporting goods.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of the Pritzlaff Building)

Fortunately, Hack’s Furniture bought the complex and used much of it for its retail store – with large showrooms (many carpeted in deep, bright-hued shag that remained in place until recently) – and warehousing.

The buildings across St. Paul Avenue (two of which are pictured below) were, with one exception that survived at least into the 1980s, were razed in the 1960s for the construction of I-794.

When it closed, however, the buildings – more than 300,000 square feet of space – sat mostly vacant, its cream city brick exterior nearly black as pitch from a century of grime.

A new life

Ken Breunig, whose Sunset Investors has been involved in numerous projects around town, including the Plankinton Arcade building, initially intended to occupy the buildings with restaurants and retail stores, but the recession of 2008 put paid to that idea. However, some events with Wild Space Dance Company and others led to the creation of two large first-floor event spaces that proved popular.

Those spaces were enhanced and expanded to include a wedding chapel (below) and support space upstairs.

Then the apartments were built out and leasing began in 2017. Over the last year or so, the apartments have had a 100 percent occupancy rate. A multi-story parking structure with about 300 spaces opened in 2018.

Offices were also added and walking through the building one is amazed by the vibrancy of life on the upper floors, where residents come and go and commercial spaces buzz with activity.

Add the nightlife that comes with the event spaces and the Pritzlaff building is likely livelier than it’s been since the hardware business was thrumming full-throttle.

And a tour with Breunig offers some interesting sights for anyone who appreciates vintage construction and historical elements.

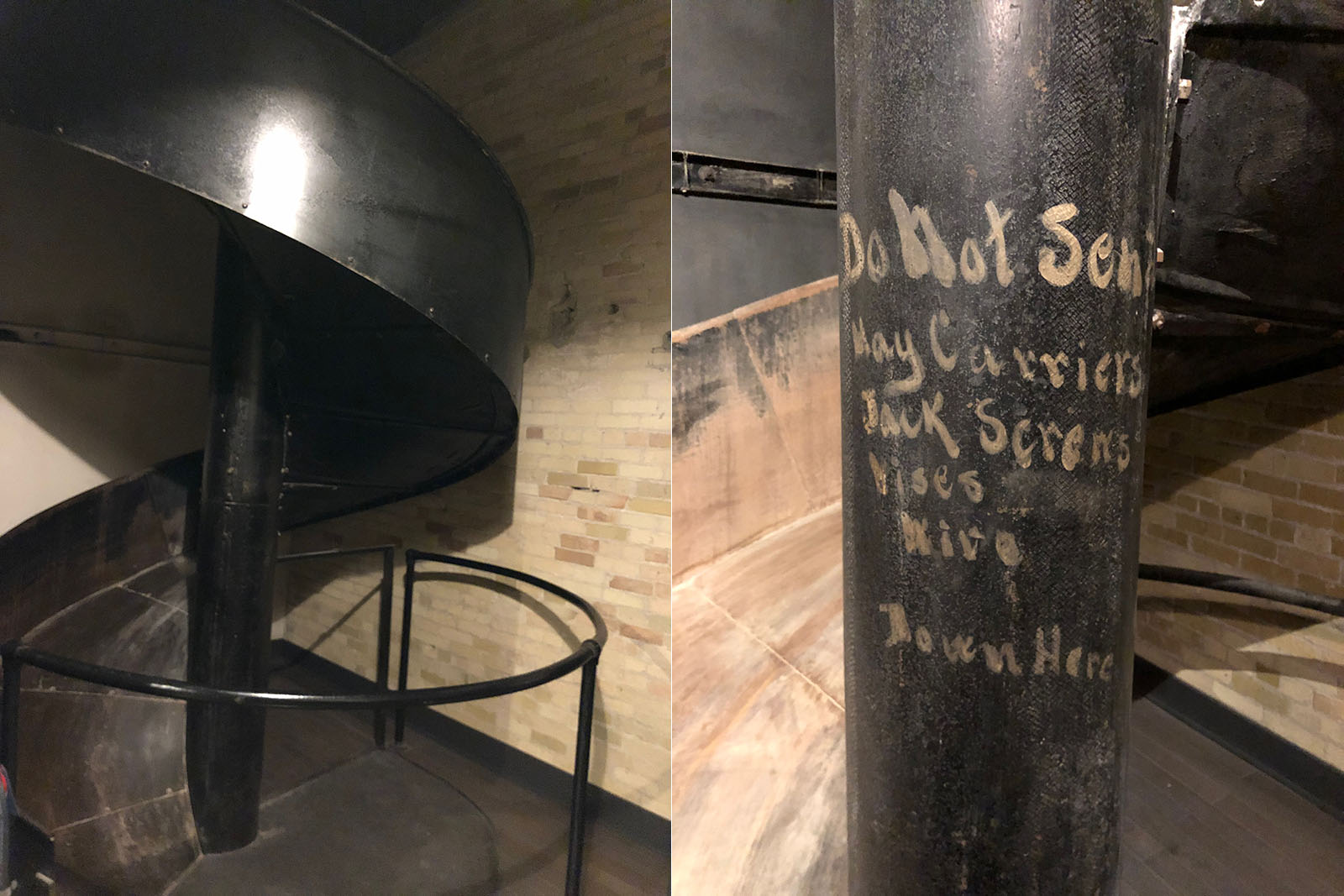

In the basement, we get to see the massive construction elements, like single-piece wood beams that measure a foot by two feet.

"We counted the rings in one of them that had to be removed," says Breunig, "and there were at least 250. And that is just the heart wood, not even the entire tree."

We also peek down into an opening in the floor to check to make sure the water level is sufficient to preserve the wood pilings that support the building.

There’s also the remnant of an old scale down there beneath the 1903 building. Keen-eyed folks at events held in the space above can spot the scale.

On the upper floors, there are hardwood floors worn from more than a century of use. There are old sliding fire doors and, in the connector, the old windows and look were preserved. On multiple floors you can see the old box slide (pictured below), too, which was used to send product down from upper levels.

And, again, there’s vintage Pritzlaff memorabilia everywhere, from framed enlargements of advertisements, catalog pages and vintage photographs, to a Pritzlaff-branded Singer sewing machine to a Door County apple sorting machine.

Perched atop benches and side tables – often constructed of wood from the building itself – are Pritzlaff catalogs that Breunig picks up periodically from a variety of sources, including eBay.

The same sources provide the commemorative Pritzlaff 100th anniversary plates – in at least three colors – that adorn the walls.

"I’ve probably got at least 60 of those," says Breunig, and you believe it, because you can plainly see how much he’s invested in this building, not only in money, but in blood, sweat and tears.

He can – and will – tell you about how he sealed the original floors in order to be able to preserve and keep them. He will show you the features he’s preserved outside – like the train tunnel (pictured below) that allowed box cars to practically enter the building for loading and unloading.

He’ll walk you into the variety of large safes in the 1887 building – some with elaborately painted doors – and explain how they’re constructed.

He knows the place inside and out and loves it so much that he keeps an apartment here.

And his enthusiasm is a big draw for some, like Kerhin.

"I was attracted to the Pritzlaff for a few reasons," the restaurateur says. "First is the quality of the building, the sturdy massiveness, the abundance of wood and brick. Secondly, the location. It's mere steps from a very population dense area of the city, yet it's almost an island: train tracks and river on the south and east, freeway to the north, post office to the west.

"The final reason is Kendall Breunig. He's committed to preservation when possible, but unafraid to put the time and money into doing it the right way when preservation isn't possible. Without him, this project wouldn't exist."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.