If you like this article, read more about Milwaukee-area history and architecture in the hundreds of other similar articles in the Urban Spelunking series here.

Can you imagine Milwaukee without The Pabst Mansion?

Somehow we manage to move forward each day without the Elizabeth Plankinton mansion on Wisconsin Avenue, without the Heineman home on Prospect Avenue and without countless other grand Milwaukee mansions erected in the 19th and early 20th century.

"Gone is gone," says executive director of The Pabst Mansion, John Eastberg (pictured below), "And I am a lifelong preservationist, but when something is gone, I even start to struggle – 'okay, what was in that corner?' Once it's gone, it's gone, and I think out of sight, out of mind."

It’s hard to believe that Milwaukee would’ve forgotten about The Pabst Mansion, 2000 W. Wisconsin Ave., had it – like most of its contemporaries – met with the wrecking ball. But, that was a real possibility in the mid-1970s, when, under a new owner for the first time in decades, The Pabst was slated to fall.

On Sunday, the staff of the mansion – which celebrated its 125th birthday last year – observed the 40th anniversary of the preservation of the grand home of Capt. Frederick Pabst, one of the city’s most legendary figures.

In 1908, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee bought the house from the Pabst family, and used it as a residence for the archbishop and others in the church’s local hierarchy. It is for that reason that the home survived as long as it did, says Eastberg.

"Archbishop William Cousins was the last archbishop to live in the house," Eastberg says.

"He moved in in 1959, and the whole house was, essentially, his. There were Sisters of St. Francis that were the staff, the housekeepers and the cooks. There were others here, but he he was using the sitting room as a sitting room, he was using the dining room, he was using the study as his study, he was using the master suite as his suite, he was the new Captain.

"The house just kind of settled into this organization in 1908 essentially the way it had started out in 1892, and so it continued to function. You still had the staff running it, and that's why everything was still polished beautifully, you know, and it just went on."

The same was not true for the other grand mansions of Grand Avenue, which, says Eastberg, enjoyed a glorious era that was much shorter than many of us think.

"Zoning changed (from single-family residential to commercial and multi-family residential) in this neighborhood in 1927, and there were just so many buildings that came down in '27, '28, because then they could build commercially up here full-throttle.

"So Mrs. Pabst's house, which was 40,000 square feet, that came down in '27. Mrs. Pabst's niece's house, where they built the Ambassador Hotel, came down '27. The Eagles Club was built in '27, '28, so you know, you start putting all these dates together and you're like, ‘Wow, this was happening a lot earlier than people think.’"

As Milwaukee’s rich and powerful moved up to new mansions on Prospect Avenue, on Terrace Avenue, on Wahl Avenue, the complexion of Wisconsin Avenue changed immensely. Now, you can count the survivors more or less on your fingers.

Interestingly, even in the 1930s, the importance of the Pabst home was clear, as is evidenced from its entry in the 1940 WPA guide to the city that was only recently published as "Milwaukee in the 1930s" ...

"The house still remains one of Milwaukee's most conspicuous examples of elaborate architecture," the book's authors noted.

"If the Archdiocese hadn't purchased it in 1908," says Eastberg, "I can guarantee it wouldn't have been here. I think the Pabst family was always happy that the Archdiocese had purchased it, because they could see that was a way to preserve the house."

The Pabst was blessed to have a function. Until, that is, the Archdiocese decided to sell The Pabst Mansion and move to Brookfield.

"It was becoming, I think, kind of a burden as far as the maintenance was concerned," says Eastberg.

That put the house – designed by George Ferry and Alfred Clas – in the crosshairs of developers, and especially of one in particular.

"(In 1974), the Archdiocese wanted to sell, and our organization was being put together right around the same time," says Eastberg. "Actually, if you line up the dates, our organization officially starts after the house has already been sold to Nathan Rakita who owned the Coach House (hotel) next door."

Luckily, H. Russell Zimmermann was working hard at this point to raise awareness of historic preservation via his columns in the daily newspaper, one of which, in March 1975, focused on The Pabst Mansion.

"If this landmark of landmarks is not capable of generating the interest and money necessary to save it from the wrecking ball," Zimmermann wrote, "it is doubtful that anything in Milwaukee can be called 'permanent.'"

Taking up that challenge, Wisconsin Heritage (WHI), the group that would ultimately save and now runs The Pabst, was founded by Fox Point interior designer Florence Schroeder in April 1975 and attempted to raise the money to buy the home.

When those efforts fell short, John Conlan, a Milwaukee businessman with a passion for preservation, stepped in an worked out a deal with Rakita.

In the two photos above: The house as it appeared in 1978.

(PHOTOS: Courtesy of The Pabst Mansion)

Conlan bought the mansion and its property, except for the northernmost section. Rakita retained that piece, tearing down the carriage house to create parking for his hotel next door.

In the meantime, WHI continued to raise money and, at the same time, struggled to get a mortgage. Until, that is, a local association stepped in.

"Finally, somebody came up with the idea of putting out an idea to the Savings and Loan Council of Milwaukee County, and I think there were 30 members of that council, and 23 of those banks each wrote a $10,000 mortgage to WHI in order to buy the house," Eastberg says.

WHI bought the house from Conlan for $330,000 on April 29, 1978.

Signing the papers on April 29, 1978. (PHOTO: Courtesy of The Pabst Mansion)

And the rest, as they say, is history. Now, we can’t imagine Milwaukee without The Pabst Mansion, which draws around 35,000 visitors each year.

"By the mid-’80s, people were regarding it highly as a major destination," says Eastberg. "It's pretty remarkable that, after all that time, it's completely self-sustaining. Being our own private nonprofit that's completely self-sustaining has actually worked out very well for us."

Visitors line up to see The Pabst Mansion in 1984. (PHOTO: Courtesy of The Pabst Mansion)

While it’s true that when something is gone, it’s gone, that doesn’t mean the loss doesn’t make us poorer as a community, whether we realize it or not.

"It would have been a tragedy," says Eastberg of the potential loss of the Pabst. "I think if we're saving – and I think that's your big goal in a community, to save the prime things, the prime jewels of a community – The Pabst Mansion, built for Milwaukeeans, by Milwaukee architects, Milwaukee craftsmen, really is what Milwaukee could produce in the 1890s. It is the highest example of something that could be built.

"We have a great name, so it's iconic in that sense, in that it's an internationally recognized name of somebody that lived here, so that helps. Architecturally, it reflects what we think of Milwaukee, with the Flemish step gables."

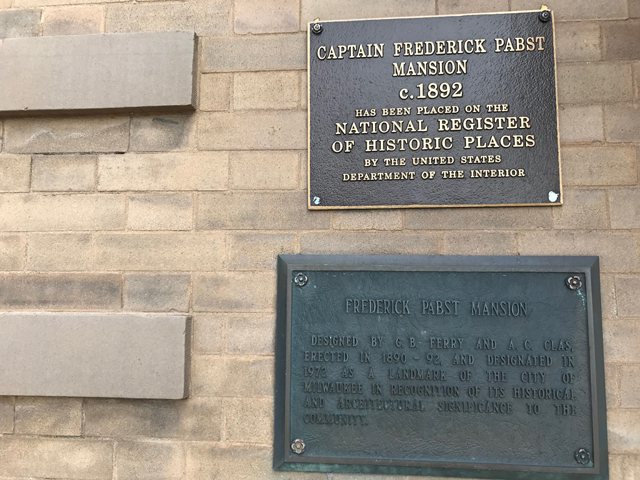

The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is locally landmarked, too.

There are still challenges, of course, like the ailing entrance pavilion, for which a plan has been detailed and fundraising is underway. But, now, The Pabst is here to stay, we hope, for at least another 125 years.

If you want to learn more about the history of this classic Milwaukee home, Eastberg will give a talk on the subject on May 10. Admission is $15. Please call (414) 931-0808 to RSVP.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.

.jpg)