Two years ago, the U.S. Census Bureau set out to count every person in the United States as mandated in the Constitution. But this time it did so as the nation grappled with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and other dynamics, including an effort to add a citizenship question, came into play.

The preliminary assessment: Post-count analysis showed that the 2020 census both overcounted and undercounted certain populations compared to data from 2010. Last month, the bureau released results from its post-enumeration survey and demographic analysis estimates.

African Americans were undercounted by 3.30% compared to 2.06% in 2010 and the Hispanic and Latino population faced an undercount of 4.99% compared to 1.54% in 2010.

Other undercounted groups included American Indians or Alaskan Natives living on reservations.

Meanwhile, non-Hispanic whites were overcounted by 1.64% versus .83% and Asian Americans were overcounted by 2.62% compared to 0%, according to the estimates.

Undercounts raise the specter of fewer federal dollars to local communities and less representation for undercounted groups in redistricting.

According to the latest figures from the Census Bureau, the City of Milwaukee’s population is 34% white (non-Hispanic or Latinx), 38.8% Black, 19.4% Latinx, 4.6% Asian and 0.5% Native American.

“There’s been a historical pattern of undercounts in Milwaukee, even dating back to the 1990s and 2000s,” said Sharon Robinson, the director of administration for the City of Milwaukee. She also served as the chairwoman of the Greater Milwaukee Complete Count Committee.

The city is reviewing census data and comparing it to its own data. If enough discrepancies are found, the city could challenge the results.

Robinson explained that in preparation of the census, the city updated its Local Update of Census Addresses Operation and added thousands of housing units since 2010.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s own population estimates from 2019 put the City of Milwaukee at over 590,000, but the 2020 data put Milwaukee’s population at 577,222.

“There’s many reasons we want to stand up for the residents of this community,” Robinson said. “A fair census is clearly a civil rights issue. We just can’t afford to get these numbers wrong.”

Why were certain populations undercounted?

Margo Anderson is a professor emerita of history and urban studies at UW-Milwaukee. She is an expert on the census and is currently on a panel under the National Academy of Sciences that evaluates why there was an undercount.

“We don’t have enough local data to say very much,” she said. “The big takeaway from the 2020 census is a combination of the controversy generated by Trump to put a citizenship question on the form and then the pandemic meant that the actual count was delayed.”

Even though the citizenship question didn’t go on the form, its possible immigrant communities didn’t respond to the census for fear of deportation, Anderson said, but nothing is known for certain.

The citizenship question was a threat to the mechanics of the count and American democracy, she said.

Donald Trump’s administration raised the possibility of the question amid already existing fears that the former president’s immigration policies and rhetoric would dampen participation in the count of undocumented citizens. The plain language of the Constitution requires an attempt to count every U.S. resident.

Trump’s administration also was hostile toward the undocumented population during its entire term, said Christine Neumann-Ortiz, the executive director of Voces de la Frontera, a nonprofit organization that advocates for immigrant rights. She said many immigrants feared that census information would be shared with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

Furthermore, the pandemic locked everything down when the most intense counting efforts were set to take place, Anderson said, and everything had to be restructured. The in-person counting phase was pushed back from spring to summer and places such as libraries that were meant to serve as census hubs were closed due to the pandemic.

Robinson added that Trump’s decision to end the count early may have stopped efforts made to reach hard-to-count populations such as the LGBTQ+ community.

Other demographics that are often undercounted include people who live in group quarters such as dorms and nursing homes. The data showed a significant drop in group quarters, Robinson said, noting that that number decreased from over 18,000 to just over 15,000.

Anderson noted that since college students were sent home they may have been counted twice or not at all, but there isn’t enough data to know.

In a statement, the U.S. Census Bureau acknowledged that it undercounted and overcounted the same population groups it has in the past.

What efforts were made to reach hard-to-count populations?

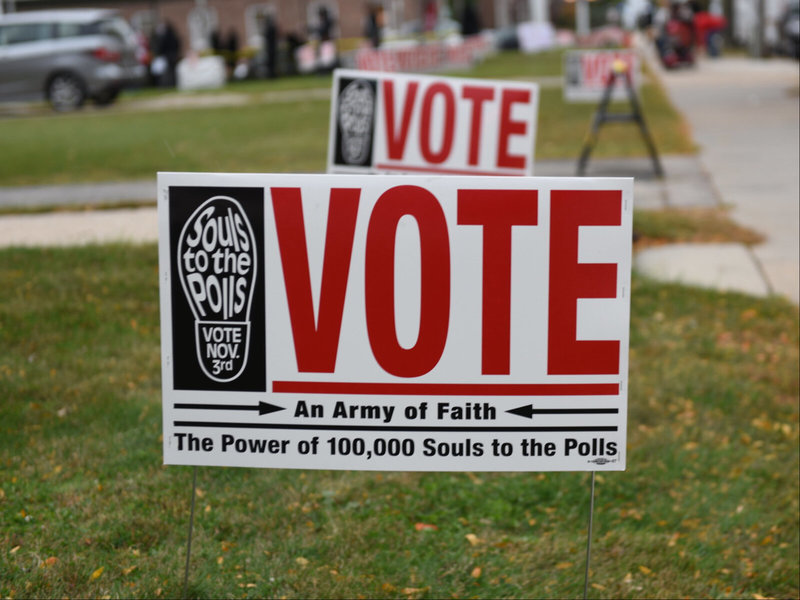

Grassroot organizations and other entities made various efforts to reach residents.

Voces de la Frontera, for example, worked with its members and activated its network, Voceros por el Voto, which first launched in 2018. It also worked with younger people to spread the knowledge.

The Complete Count Committee worked at COVID testing sites, food centers and grocery stores to spread the word. Methods included sharing information through the mail in partnership with other organizations such as the Housing Authority and working with schools to hand out census coloring books.

“One of our major challenges was that we were actually restricted from doing the door knocking due to restrictions related to COVID,” Robinson said. “I think this hurt us in many ways.”

The U.S. Census Bureau noted that it established 152 statewide Complete Count Committees and its staff called, texted and emailed nonresponsive households.

“In the case of the Latinx community, we also worked hard to educate people that the citizenship question was not included on the census form, but we acknowledge that the conversation and litigation around its inclusion may have created confusion,” Census Bureau leaders said in a statement. “We believe those efforts were beneficial but not could not fully overcome the unprecedented challenges of 2020.”

What potential impact will this have on Milwaukee?

“The census data is used to determine the distribution of more than $675 billion in federal funds to cities and counties and states,” Robinson said. “That’s funding for schools, hospitals, housing, jobs training and so many vital programs. If we don’t get our numbers right, each resident that goes uncounted is going to suffer.”

According to the George Washington Institute of Public Policy, each resident could lose about $1,584 in funding every year, Robinson said.

The data also determines the districts of the state Legislature and the number of seats Wisconsin gets in Congress. States that gain population also gain congressional seats, and population losses can result in fewer congressional districts for states.

In a prepared statement on the 2020 census, Robert L. Santos, the director of the U.S. Census Bureau, said, “We believe that the 2020 census data are fit for many decision-making as well as painting a vivid portrait of our nation’s people.”

Santos acknowledged that there are areas of concern that the bureau will be looking into. But Anderson said local officials should wait for the data to be available before raising concerns. “We don’t know if those counting problems were specific to certain parts of the country,” she said.

Why should people care?

“If we don’t get our numbers right, it affects every resident’s voice in government,” Robinson said. “The Constitution even says that every single person that lives in the United States has the civil right to be counted in the census and no one should be left uncounted.”

She said unfair policies that prevent someone from participating in the census should never be allowed to occur, because it is a violation of civil rights, she said. “For every resident that goes uncounted, we all lose,” Robinson said.

What efforts can be done to ensure a more accurate count in the future?

Robinson believes some of the changes can start with the terminology such as “hard to count.”

“We all need to do a better job,” she said. “They are not hard to count, we just need to find other methods to reach people who are marginalized by U.S. political life and civic life. It’s a problem we should all own instead of saying people are hard to count.”

Part of this work includes creating an environment in which people have more trust in the government, Robinson said. There are a lot of misperceptions, she said, and using local groups and residents to champion for the census could increase participation.

In the future, there needs to be more investment in the work, Neumann-Ortiz said, particularly “those key organizations that are really a hub for community engagement, that have networks in the community, that are rooted in the community and are trusted.”