(NOTE: In June 2021, Malteurop announced it would idle the Milwaukee plant and lay off 28 workers. That story is here.)

The former Froedtert Malt Complex, just off Miller Park Way, at 38th and Grant Streets in West Milwaukee, looks – from a distance – like a small, second downtown, with a skyline profile of its own.

"I’ve lived in Milwaukee my entire life," says Malteurop's Marketing Specialist Gretchen Jones. "I remember driving by those iconic silos a thousand times and always wondered what was inside. I learned late that those towers held that malt that made the most well-known beer of all time! The beer that I drink today!"

In recent years, you could be forgiven for thinking the plant, now owned by Malteurop – which, based in Reims, France, got started in the 1960s as a farmer cooperative and and has five North American plants and many more across the waves – is idle. From the street, you can barely hear it or even really see the side where the action is.

But walk through the front gate and you can immediately smell it.

Some days its the grainy scent of raw barley. Other days the cucumber-forward perfume of the germinating barley takes over and still other days, the smell is smokier, roastier, thanks to the activity of the drying kilns.

Not only is the Milwaukee maltster not idle, the roughly 100 employees here produce tons of malt each year – all of it destined for beer, from craft brewers like Third Space to macro giants, and whiskey distillers across the country, including some in the heart of Kentucky bourbon country.

Recently, I had the chance to take a tour of the plant.

Some Froedtert history

As brewing and distilling boomed in mid-19th century Milwaukee – and boom they did – the demand for malt also ramped up. While some breweries – think Pabst and Schlitz – had their own malt houses, others, like William Gerlach, snapped up breweries and converted them into maltsters.

In 1875, brothers William and Jacob Froedtert, born in 1852 and 1845, respectively, in Nordheim, Germany, started the Froedtert Brothers Commission Co. at 510 Juneau Avenue, likely trading in grain, seed and feed – the products lines in which William had learned the trade as an apprentice.

William Froedtert. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Malteurop)

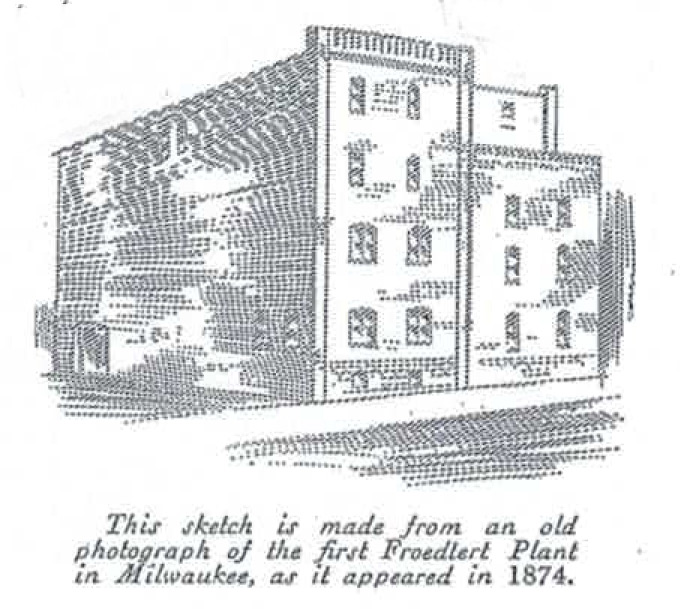

According to a 50th anniversary booklet printed in 1925, "A few years thereafter this company purchased a brewery, which due to a serious fire, had only a very small and extremely old-fashioned floor malt house remaining, and incorporated the firm Froedtert Grain & Malting Company with a total malting capacity of 50 bushels a day, operating about eight months in the year."

That brewery was founded in 1853 at 7th and Cherry Streets by John H. Senne, Joseph Hohl and John B. Maier in 1853 and was taken over by Hohl and Maier in 1855, according to brewing historian Leonard Jurgensen. By the late 1850s, the brewery named solely for Maier, a former brewmaster at Stoltz & Schneider, located east of the Milwaukee River on Ogden Street.

By 1860, the brewery was making about 2,000 barrels a year, which increased by 50 percent by 1867. In 1868 it was called Western Brewery.

Maier and his wife sold their shares to John Kargleder in 1870, according to Jurgensen, and took Frederick W. Manegold on as a partner a few months later.

By 1874, Western was churning out more than 18,000 barrels annually.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Malteurop)

In an interesting twist, in 1874, the facility became home to the Milwaukee Brewing Association, which was owned by Albert Blatz, elder brother of the better-known brewer Val Blatz.

When Albert Blatz died in 1881, says Jurgensen, "control and ownership of the (Milwaukee Brewing Association) was transferred to Emil Schandein, the(n) current vice president of the Best Brewery, which (would) soon become the Pabst Brewery, and Captain Frederick Pabst, who (were) now partners in the Milwaukee Brewing Association Brewery."

A fire in 1882 damaged brewery and it was bought by Charles Westhofen, who a month later sold half his interest to Jacob Froedtert, according to Jurgensen, and a malting company was established.

In 1884, Westhofen sold his half of the company to Jacob’s brother, William, and, thus, was the Froedtert Malting Company officially born.

When Jacob died at age 41 in 1886, William kept the business rolling.

Indeed, the company history notes that after Jacob died, "the entire responsibility rested on William Froedtert. His progressive and practical conceptions of business kept step with, and in some of its adaptations to new principles, advanced the scientific progress of the industry. This being his life’s center and hobby, slowly the business added buildings, increasing its capacity accordingly. His beauty of mind and character, lofty ideals of conduct, perfect fidelity to duty and all manly virtues, made his firm stand out as one of the best."

That progress was seems to have been anything but slow.

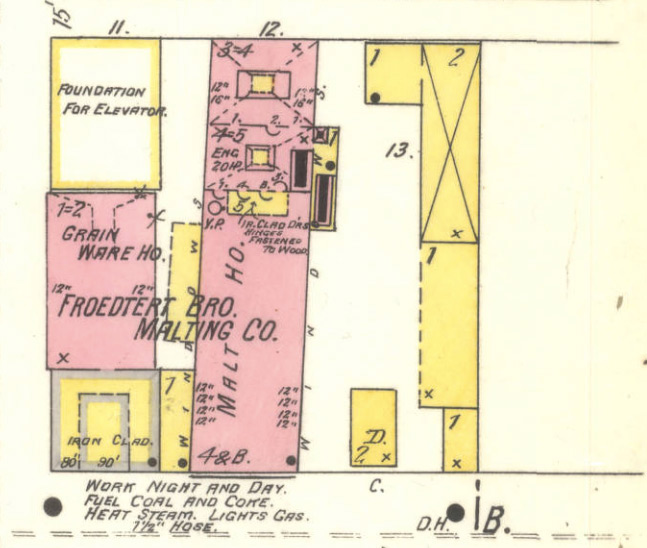

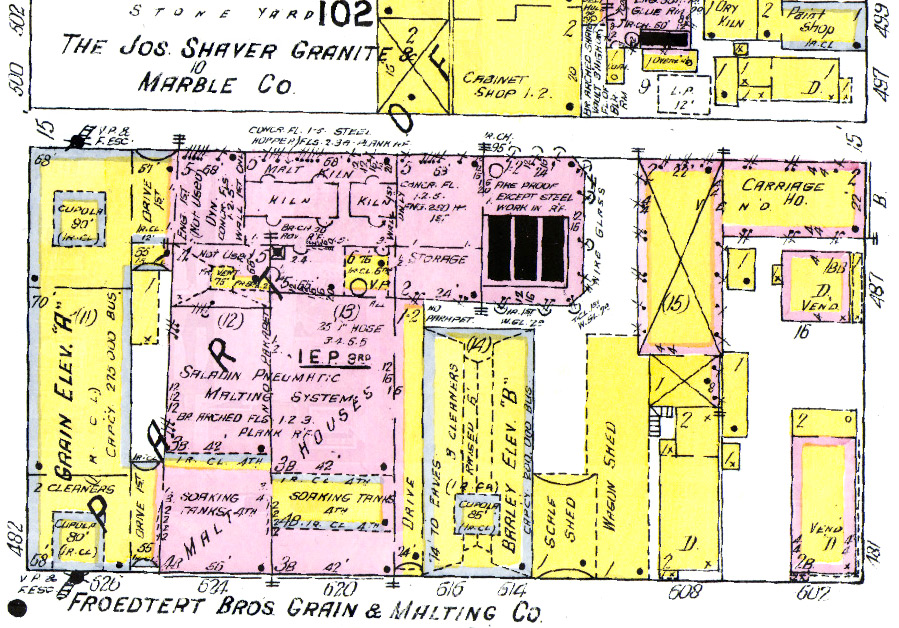

Comparing the 1894 (above) and 1910 (below) Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps shows Froedtert growing eastward to fill the entire block south of the alley with its ever-expanding facility.

"As additional capacity was much needed, more buildings were added from time to time so that the malting capacity was increased to 3,000 bushels per day," the company booklet says.

In addition, by about 1910, the company also owned the Winona Malt & Grain plant in Winona, Minnesota.

After William Froedtert’s death in 1915, his son Kurtis, who he'd been grooming as a replacement, took over the company. A photo (courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society) taken that year by Milwaukee’s Kuhli Photo Service, depicts Froedtert seated behind a desk in his office draped in what looks like an animal hide and adorned with flowers, a taxidermied bird and other objects.

The younger Froedtert, born in 1887, reportedly in a basement near 6th and Vliet Streets, studied first at Milwaukee’s German-English Academy and then at the Michigan Military Academy, where he graduated in 1904 at the top of his class.

He had dreamed of becoming a doctor, according to Jurgensen, who notes, "Because of Kurtis Froedtert's interest in medicine and in science, he ... originally planned to attend medical school.

"He had received scholarships to three Ivy League colleges, as well as the University of Chicago Medical School. However, due to his father's continued health problems, he was forced to decline that opportunity and to stay close to home, working in the family business."

As was the case for its customers in brewing and distilling – as well as most everyone else in an era of wood-frame construction – Froedtert’s plant was susceptible to fire, thanks in part to the kilns used to dry the malted barley.

In 1921, a blaze destroyed the interior of Barley Elevator B, which stood smack dab in the middle of the complex, causing injury to some employees who were inside and failed to detect the fire in time.

The 50,000 bushels of barley in the elevator were damaged by smoke and water and, according to one news report, much of it "was swept down the street."

Froedtert also processed other grains. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Malteurop)

The move west

The fire, it seems, also swept Froedtert out of the central part of Milwaukee, to 38th and Grant Streets, in what was then wide open territory.

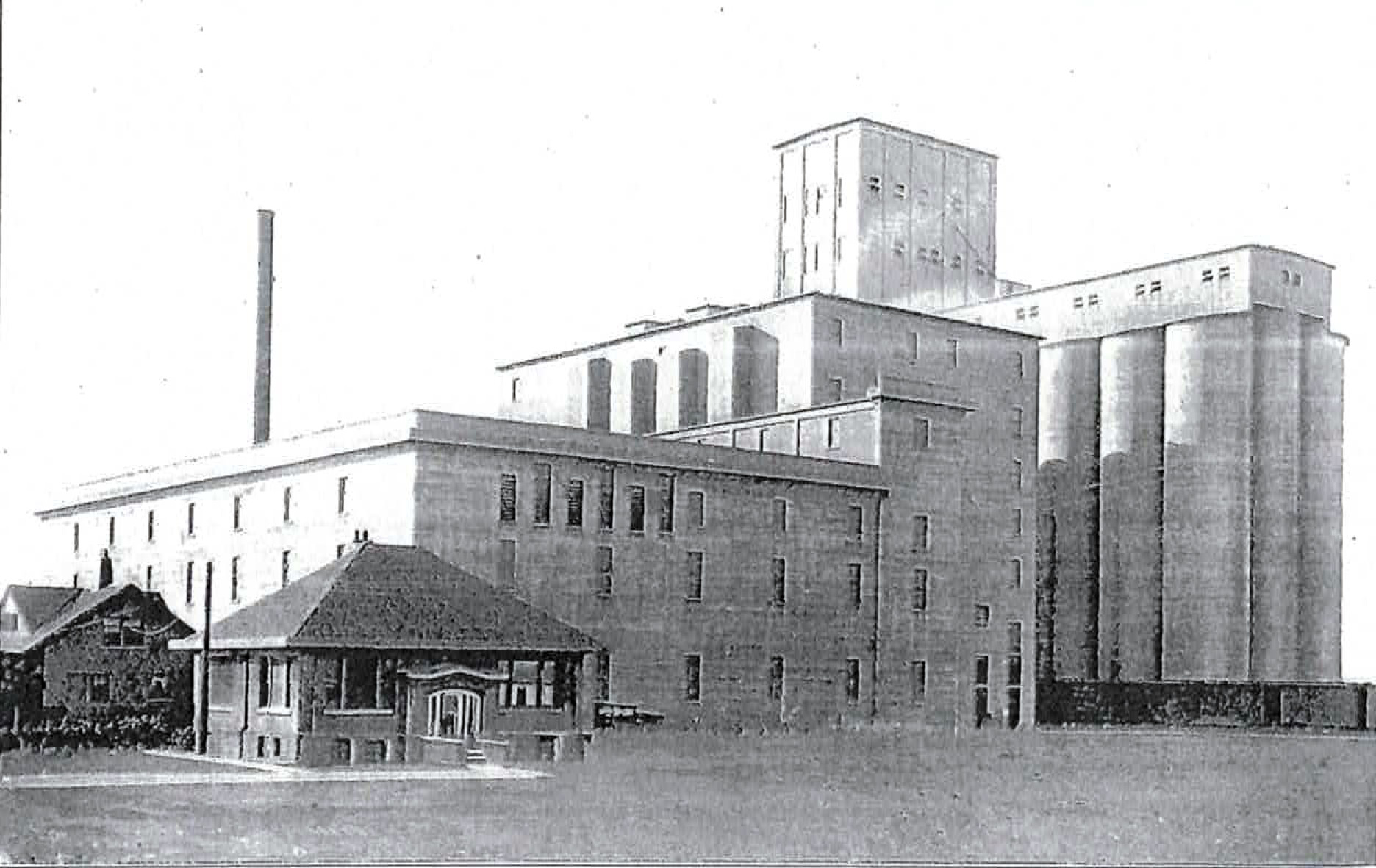

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Malteurop)

"A big reason for this building on this site was the fact that at the time there was nothing here it was just flat open field," says Malteurop’s Jones. "So there was a lot of space to build on, but they also had the transportation of the trains running right here so that really lent itself to facilitating transporting all over the country."

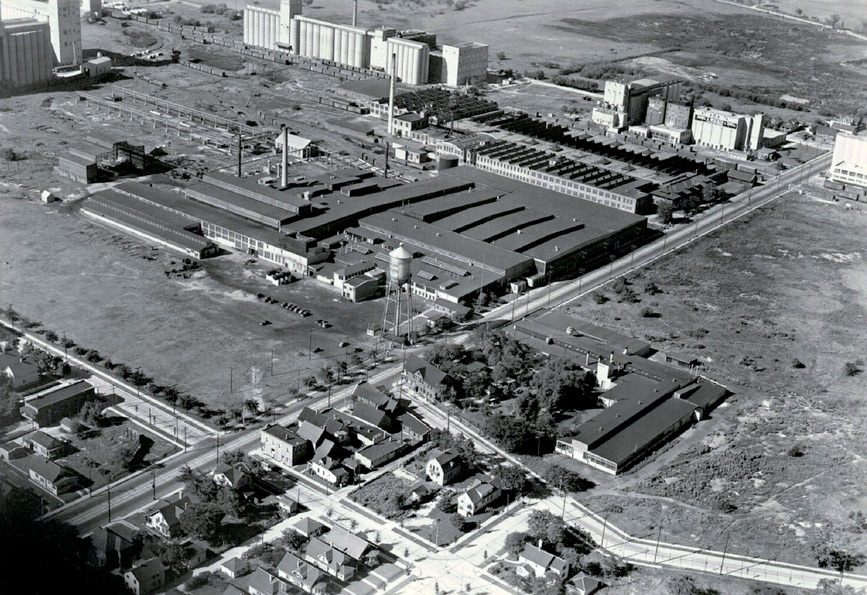

A 1930s WPA guide to the city, noted that the area – then in the Town of Greenfield – was one "of mammoth concrete grain elevators and malting and milling plants known as Milwaukee’s principal malting and milling district.

The plant in 1939. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Malteurop)

"Here, centering between West Lincoln Avenue and West Mitchell Street and extending from South 43rd Street to South 37th Street, are four large plants: the Froedtert Grain and Malting Company, the Kurth Malting Company, D.D. Weschler and Sons, Inc. and the Charles A. Krause Milling Company."

The 1925 company history boasts of the modernity of the West Milwaukee facility.

"The Milwaukee plant ... is the most modern and the largest malting plant in the world under one roof ... with an annual malting capacity of four million bushels ... 875,000 bushels of grain may be stored at the Milwaukee plant. The battery of 18 big concrete and steel tanks protects the carefully selected grain from all hazards. The immense storage capacity of our plants enable us to buy the best grain on a favorable market and thus protect our customers from price."

The Winona plant was second only in size to the Milwaukee facility, too, according to that history, and Froedtert had grain elevators in Fredonia ad Colgate, Wisconsin, and Marshall, Red Wing and Taunton, Minnesota, too.

In addition to sales offices across the country, there were also locations in Cuba, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Italy, Switzerland, England, France, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany and Belgium.

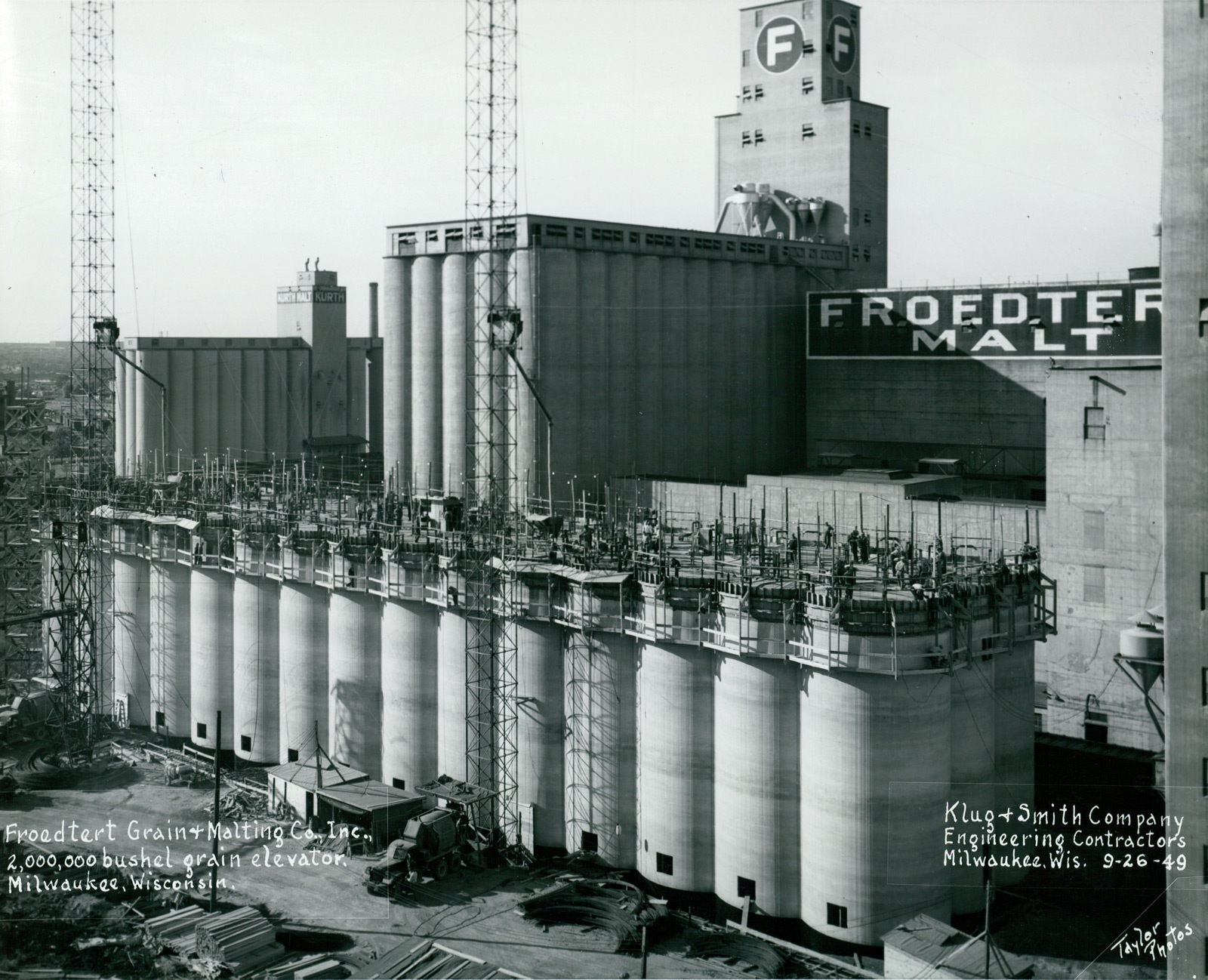

Photographs in the company archive show construction not only during the 1920s, but there are images of grain elevators and other buildings going up again in 1946 and again in 1949.

Construction in 1946 (above) and 1949 (below). (PHOTOS: Courtesy of Malteurop)

These photos also show an on-side residence – complete with chicken coop – where the master maltster lived with his family, amid the roar of the kilns and the clatter of trains rattling in and out of the plant, carrying barley to Froedtert and finished malt to customers.

One such former residence still survives at the plant.

In the late 1930s, according to the WPA guide, Froedtert was the world’s largest commercial malting company and its campus boasted, "six rectangular brick, steel and concrete buildings of varying heights and 70 towering cyclindrical concrete bins that look like overgrown silos. The combined malt storage facilities, including a recently completed addition of 750,000 bushel capacity, aggregate 6,300,000 bushels.

"It has expanded rapidly in recent years, keeping pace with the growing brewery industry it serves. The company buys 13 million bushels of barley annually and produces about 12 million bushels of malt each year; it employs 250 persons."

Unlike his father, Kurtis Froedert – who can be seen – had hobbies outside the barley business, including breeding prize milking goats.

Froedtert – who in the early 1920s, as the 18th Amendment was surely cutting into his business, penned a booklet called "What Has Prohibition Accomplished?" – was also active in real estate and had an early hand in the development of a number of malls in the Milwaukee area, including Southgate and Westgate, which was later renamed Mayfair, and Northgate, which became Capitol Court.

"The Milwaukee shopper will be able to make a single, free parking stop at the S. 27th St. center and do all of her day’s shopping, comfortably and conveniently, without worrying about her car, the weather outside or carrying her purchases around with her," John Gurda quotes Froedtert as saying in 1949 when he unveiled plans for the malls.

Upon his death in 1951, Kurtis Froedtert – who had amassed an impressive fortune – left $11 million to Milwaukee in trust to fund the creation of the hospital that still bears his family name, using a fortune built on beer to create an important local health care facility.

At that point, the company’s annual sales had surpassed $35 million, which, adjusted for inflation, is about 10 times that amount today.

New buildings on a new site with new technologies could reduce the risk of fire, but, as a 1962 malt elevator explosion proved, the business – as as in distilling and brewing – comes with some danger.

According to Fire Engineering magazine, "An explosion and flash fire, involving malt and residue in 39 tanks, swept through Elevator No. 3 at the Froedtert Malt Corporation, West Grant Street, West Milwaukee, on July 12. Causing damage estimated at $1 million, the fire gave the local department one of its toughest workers in years, with the last line shut down four days after the first alarm was received."

Elevator 3 – which was 145 feel tall, 65 feet wide and 280 feet long – was built in 1949 with 45 separate storage bins that were 135 feet tall and 24 feet in diameter. At the time of the blast, the tanks held about 1,425,827 bushels of finished malt.

Some buildings, including grain elevators, at what had been dubbed the "west plant" were closed in 2003 and demolished not long after, the land sold for development along Lincoln Avenue and Miller Park Way.

In 2008, Malteurop purchased Froedtert. Before that, Froedtert was part of Lesaffre, which, in 1998, merged with Archer Daniels Midland.

Inside the plant

(PHOTOS: Malteurop)

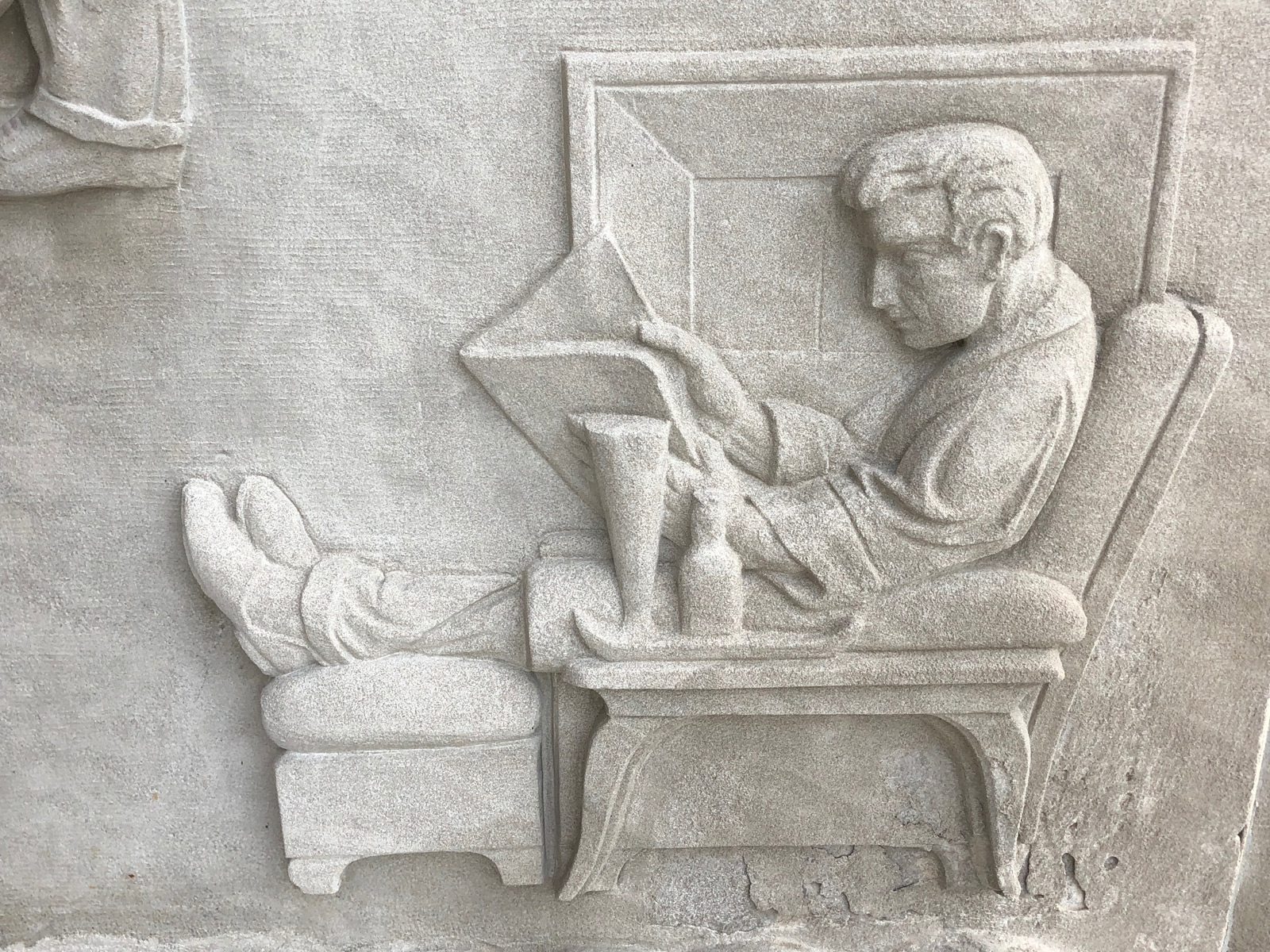

The 1950 headquarters and production offices and labs are hidden gems, tucked away on a back street. The entrance to the HQ building is framed by a stone frieze that conjures socialist realist works tracing barley from the farm to the maltster to the brewer to the consumer.

The frieze was designed and executed by Milwaukee Dick Wiken. Meanwhile, Bohemian-born sculptor and medalist Gustav Bohland created three statues – Bird and Fish, The Sower and The Reaper – that are also here.

Inside, the original board room has a lovely recessed ceiling, wood paneling adorned with still more art and, in true "Mad Men" style, an adjacent wet bar.

In the production building next store, there are labs for testing the barley when it arrives to make sure it will properly germinate, and offices for staff. Along one corridor wall there is a tantalizing selection of photos from the company archive, including a couple great ones showing a train car tilter, which lifted a box car first one way and then toward the side to empty the barley upon arrival.

Malteurop’s Plant Manager Bob Wright says that the tilter is still there but is no longer used. Sadly, it’s not something we’ll see on our visit. But that’s OK, because what we will see is super interesting to a beer and whiskey geek like me.

Before we head into the malt house, Wright gives me some background.

"We make a little over 100,000 metric tons of malt a year," he says, out of a total of 2.2 million tons across Malteurop’s 27 facilities in 14 countries.

"A number of the structures you see onsite are no longer operating, two of the grain elevators are operating and one of the malt houses. Elevator 3 over here is all malt, and there's another barley elevator in back."

He also explains the basics of the process, which despite technological changes that have made some of the work easy – mostly computers that help track parameters and recipes, etc. – it’s a process that hasn’t changed much over the centuries.

Making malt

"We take the barley in by rail, 99.9 percent of it," he says, noting that the remainder is trucked down from a farm near Green Bay that provides Wisconsin-grown barley destined for Badger State craft brewers. "We test the grain before it comes so that we know that it will germinate. We clean the barley and put it into storage, transfer it over to the malt house, and we put it into the process, which is pretty simple: you soak it, you grow it and you dry it.

"We call it an eight-day process, but really it's eight abbreviated days, like a 21-hour day, that's our current cycle. We steep the barley for two of those days, soak it in water, alternating with air rest."

The steeping room looks a lot like a space you’d see in a brewery or distillery, with giant open tanks full of what looks at first like thin barley soup, but over time starts to look less wet.

"At the end of the steeping process it's sampled and evaluated for growth ... you can actually see the growth starting develops a little nub of rootlets. Then we put it in great big germination boxes, where we level these piles, put more moisture in there, keep it in a cool humid environment for four days.

In the germination room, there are great big "boxes" for lack of a better word, full of the already-steeped grain. In here, the cucumber scent is strong, and the visual of the almost endless landscape of tan barley is equally striking.

At the end of each box – the sides of which are notched like gears, there’s a machine that agitates the barley to make sure it germinates evenly. The same machine can also add moisture as necessary and is used to move the barley into the boxes in the first place.

"You'll see rootlets on the head a sprout or acrospire growing and that's what the maltsters look at, they evaluate the length of that sprout during the process to see whether they need to put more water on or extend the cycle to develop the final product that we need," says Wright.

Wright explains, “Distillers like a high enzyme package because corn doesn’t have them so the malt enzymes have to convert all of the corn starches. The additional growth required for higher enzymes tends to generate a lot of rootlets, thus the hairier appearance.”

A craft brewer needs less of that growth for a good brew, and, says Wright, a macro brewer is looking for something in the middle.

Here we taste the barley and it’s got a familiar barley flavor but with a greenness still present.

Next, we head into the kiln – which looks much like the germination area, though darker and a heck of a lot warmer – where the temperature reaches 165 degrees and holes in the ceiling help maltsters re-use the rising heat to get the next batches get going upstairs.

"It’s one of our ways of conserving energy," Wright says.

"In the kiln area we dry it down and arrest the growth," says Wright, "and that's where we're developing the flavor compounds and some color as well as we dry it down. That takes roughly two short days, and then it goes into the elevator where it's cleaned and goes into storage then we clean it again and put it in rail cars, trucks or bags."

Again, we sample a few kernels and most of the green flavor is gone, replaced with a sublime nuttiness that also fills the air in this space.

The malt is cleaned with a big vibrating screen with different-sized holes, which allow the dust, husks and rootlets to fall through, leaving pure, clean malted barley.

The plant runs 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

Other than the grain obtained from the Green Bay-area farmer, most of the barley is grown somewhat more distantly, says Wright.

"There's very little barley grown in the Midwest other than the Dakotas now, so we bring in some Dakota barleys, from the inner mountain region out west and up into Canada, as well ... Saskatchewan, Manitoba, those areas grow a lot of barley."

While some of the other North American Malteurop plants provide malt to food producers, for things like granola bars, baked goods and breakfast cereal, the Milwaukee plant does not. Every bit of grain that leaves the maltster here is destined for beer or whiskey.

Of course, there are lots of variables and Malteurop uses about a dozen barley varieties to create about a dozen different final malt products.

"We make a couple primary classes of malt and then there's all the varieties within them as well. Elevator management gets a little complex," he says with a smile. "The varietal (of barley) has a big play in (the final product) but really it's the science and art of malting that generates the final result. A brewers malt for a craft brewer is different from a brewers malt for a big brewer, and way different from a distilling malt. It's all just how they manage the process."

Malteurop also has its own barley breeding program via which it creates barley varieties to suit its customers’ needs and wants.

(PHOTO: Malteurop)

In the past, nearly everything left the plant in train cars, but nowadays, with the craft beer boom, much of it leaves in 55-pound bags that come off the bag line that was installed a few years ago.

Next time you pop open a can of Wisconsin beer or American whiskey, you may be tasting barley that was malted in Milwaukee, further cementing the city’s reputation as Brew City.

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.