Driving past, the building that houses MPS’ Alliance High School, 850 W. Walnut St., doesn’t really look like much. But you get the sense that there’s more than meets the eye at this place that looks, from the side that we can see from the street, sort of like a school and sort of like an industrial building.

After years of wondering, I decided to find out more. When art teacher Jill Engel-Miller invited me in for a tour, I realized that simply approaching from the west already offers a whole new perspective. That was – and still is – the main entrance and the side everyone was meant to see when the building was erected in 1914 as the social center for the new Lapham Park.

At that time, North 9th Street was still open and the west facade was more elaborately decorated. What we see as the "front" now – that is, what we see from Walnut Street – is actually the side of the building.

But the original orientation and decoration is just a fraction of the interesting history I discovered about the building, which houses what Teen Vogue called one of the coolest high schools in the country a few years ago, writing:

"High school can be a tumultuous time for anyone (growing up will do that to you), but research shows that certain students feel the struggle more acutely: LGBTQ teens are more likely than their peers to suffer from depression and have thoughts of suicide. To tackle this issue head on, Alliance High School was founded in 2005 as a safe space for all teens – no matter what their sexual orientation may be.

The school's policy of acceptance for all and zero tolerance for bullying has made it a haven for students (gay or otherwise) who have faced harassment in more traditional school environments. Part of the Milwaukee Public School system, Alliance has expanded to serve middle schoolers as well as high schoolers, making it the first educational institution of its kind in the States."

For this one, I think we have to go way back. Trust me, it’s worth it and I promise the road will lead back to the building you see today.

Forty-Eighter Charles Quentin

Johann Christian Carl (aka Charles) Quentin was born in Bückeburg, a town in the Lower Saxony state of Germany in 1810, the son of a doctor. After studying law, he became a councillor in the Royal Government of Dusseldorf, where he worked in an office that oversaw state subsidies to business.

When an uprising hit Dusseldorf in 1848, however, Quentin and five of his colleagues sided with the revolutionaries in campaigning for democracy and civil rights, leading him to be disciplined and suspended when the government quelled the unrest.

So, in 1850 Johann left for America, where he traveled widely, visiting Wisconsin, New York, Illinois, Ohio, Missouri, Michigan, and some of the New England states, and wrote a book about it.

Interestingly, the city of Dusseldorf bestowed a gift and a letter of thanks to Quentin (and other so-called Forty-Eighters, named for the year of the uprising) upon his departure from Germany, where his travelogue, "Travel Pictures and Studies from the North of the United States of America," was published in 1851.

That same year, Quentin moved permanently to Milwaukee with his wife Charlotte. Here, they had three children and Johann, now Charles Quentin, entered the real estate game, purchasing property from pioneer Dutch settler Garrett Vliet, who had surveyed a large portion of the land that became the west side of Milwaukee.

Newspaper advertisements suggest that Quentin was especially active in real estate in the second half of the 1850s. In 1860, he was elected to the Wisconsin State Senate, where he served until his death in May 1862.

After his passing, Charlotte took the kids and returned permanently to Germany. Because Quentin had also served on the Board of School Commissioners from 1860 until 1862, the Ninth Ward Milwaukee public school was named in his honor.

In 1864, a big chunk of Quentin’s land – including his former homestead – became Quentin’s Park, which owners Wolf & Schuengel boasted was "a beautiful park with its magnificent altuation (sic), only eight blocks from the Chestnut Street bridge, will be open every day through the summer season. Refreshments of every kind ware also on hand."

The park opened with a much-ballyhooed dinner on June 2, 1864, one that was, thankfully, reviewed in the Sentinel two days later:

"About 150 invited guests assembled at Quentin’s Park on Thursday evening, to partake of a supper prepared by the gentlemanly proprietors, on the occasion of the formal opening of the park to the public. The supper was called an Asparagus Supper – so named because asparagus, prepared in the best manner possible, was the first dish served. After full justice had been done to the excellent repast prepared by mine hosts, Wold and Schnengel (sic), wine was brought on.

Then, of course, speeches were made, songs sung and there was good time generally. Quentin’s Park will hereafter be open to the public. It is the most beautiful spot in the city. From the crest of the knoll in the center of the park can be seen ‘the fair white city on the shores of the murmuring Michigan sea.’ Our city is a beautiful one, and a sight of it from such a point will repay the trouble of going to Quentin’s Park."

Schlitz buys the park

In the summer of 1879, Quentin’s Park was purchased by Schlitz Brewing Co. and transformed into Schlitz’s Park, a seven-acre playground with a pavilion, a pair of fountains, a concert hall and other amenities.

According to Frank Abial Flowers’ "History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: From Prehistoric Times to the Present Date …," published in 1881:

"In the center of the grounds is what is termed ‘Lookout Hill,’ an elevated plateau 40 feet high, and ascended by means of stairways at the north and south sides. It contains also a pavilion and seats of rustic beauty. … The main building, situated near the north of the park, 150x150 feet, is very attractive, and consists of three departments. The main floor, used for concerts, theaters and balls, has a seating capacity of 5,000. There are also a dining room and ice house. East of the main building is a pavilion, built in the Turkish style, used as a confectionery stand.

On the ground are gymnastic apparatus for the various societies, and seats for 1,000 people. … To the right of the entrance is the Schlitz’s Park menagerie, containing various wild animals.The Schlitz’s Park Hotel, a large establishment near the main gate, is run in connection with the park by Mr. Otto Osthoff, who is also manager of the park. Its cost, including buildings and improvements, is estimated at $150,000 (note: about $3.7 million in 2018 dollars) and during the summer months the park is frequented by all classes of people. Schlitz’s Park has accommodations for 20,000 people."

By 1909, the city was in talks with Joseph Uihlein to buy the park and the idea of changing the name to honor Increase Lapham was already being floated, according to an article in the afternoon paper that summer:

"The name of Schlitz Park will be changed if the city buys it. The city officials do not believe the city owes anything to the name Schlitz in this connection, and will immediately wipe out the name. If the park was a gift, Ald. Smith says the name Schlitz would not only be retained, but a granite monument would be erected in the park. He also suggests the name Lapham as a name for the park, but would also be pleased with Jefferson or Jackson. He thinks I.A. Lapham, the Wisconsin scientist, ought to be honored in naming one of the new public parks.

A considerable portion of Mitchell Park was a gift to the city, so the name was retained. Mrs. Gordon have so large a portion of her interest in Gordon Place that that name is also likely to be retained. Since the building committee of the council visited Schlitz Park and called upon Joseph Uihlein, obtaining from his the lowest price at which he will dispose of the park to the city, Chairman Strachota has called no meeting of the committee and no vote has been taken on the subject. So no report was ready for the common council Monday, and the matter goes over for two weeks."

Lapham Park and the Social Center movement

The purchase was made soon after and by the following January, the Journal reported that the name had officially been changed to Lapham Park. In 1915, 30 of Lapham’s friends – members of The Old Settlers Club of Milwaukee County" – chipped in from $2 to $25 to raise $420 to commission a bronze plaque in honor of their old chum and mount it on a 40,000-pound granite boulder that was set in the park. The rock was moved to a site next to Lapham Hall on the UW-Milwaukee campus in 1965.

By 1914, the social center movement had been underway already for a few years, boosted by a 1911 speech in Madison by then-future President Woodrow Wilson, who said, "The object of the (social center) movement is to make the schoolhouse the civic center of the community, at any rate in such communities as are supplied with no other place of common resort. … What you do is to open the schoolhouse and light it in the evening and say: 'Here is a place where you are welcome to come and do anything that it occurs to you to do.'"

Milwaukee Public Schools had already gotten on board and kept the lights on at a number of schoolhouses – dubbed, appropriately, "Lighted Schoolhouses" – in the evenings as neighbors were welcomed for a variety of classes, activities and clubs. One of the social center movement's earliest proponents here was Robert Witt, who, as assistant principal, had embraced the program at Fourth Street (now Golda Meir) School.

"About 24 years ago, when I procured permission to make use of the Fourth Street School for the benefit of the neighborhood, the teachers were aroused," wrote Isador Horwitz in a letter to the Journal after Witt’s passing years later. "They felt that THEIR classrooms were being desecrated. However, it was Mr. Witt, then vice principal of the school, who became the revolutionist. He agreed to my assertions that a teacher is a servant of the public and that he or she is a mere part time custodian of the building, which at all times during the 24 hours of the day belongs to the neighborhood. Mr. Witt helped greatly in the development of the social center movement."

When MPS’ recreation extension department was created in 1912, Witt was a natural and was – along with Dorothy Enderis and a few others – named an assistant to director Harold Berg. And when a dedicated social center was created at the new Lapham Park – which over the years has been home to numerous schools, including Lapham Park Open Air School, Ninth Street School, Roosevelt Junior High/Middle School and Elm Creative Arts – Witt became its director.

The building, designed by Van Ryn & DeGelleke, who did much work for Milwaukee Public Schools in the first couple decades of the young century, was erected, facing 9th Street, which then still ran past. That’s why the main entrance now appears to face away from the street – not because the building has been moved, but because its street is no longer there.

The building looked much like a school, with two entrances, finely decorated, at either end and an engraved "Lapham Park" nameplate in the center. Though the south entrance and the nameplate survive, a much later addition has obscured the north entrance. However, the decoration from the old entrance was saved and installed on the entrance to that stairway addition.

In 1925, the building was expanded to the east, with the addition of the gym. A tunnel connects the building to Roosevelt Middle School nearby, as that school’s heating plant also warms the social center.

Thanks for current school board member Larry Miller, who was lead teacher at Metropolitan High School – which occupied the building from 1996 until 2009 – there are copious photos of the activities at the social center from across the years. Miller led a student project that collected photos and memories of the center and the Bronzeville neighborhood.

Now, one can see children shooting marbles out front, having costume parties and staging performances inside; playing basketball and other sports in the gym, where banquets and other functions were also held; getting immunizations from white-coated doctors.

There are strapping lads lifting weights, dainty old ladies sewing and teens playing table tennis. In one room – "Newsies" fans alert! – the "Newsboys Republic" can be seen holding a "congress." There’s a portrait, like a class photo, of a billiards team, each man holding a cue, and a shot of an elderly couple apparently selling snacks at a small stand.

A man plays an upright piano, in another shot, as a group of boys gathers around to listen. Local jazz musicians like guitarist Manty Ellis and internationally acclaimed singer Al Jarreau have recalled playing music at the Lapham Park Social Center, which had its own bands as far back as the 1920s.

Another image shows a boy reaching first base at the same time as the ball lands in the opponent’s mitt. One photo depicts a group of ballerinas.

Clearly, the social center served many needs of countless children and adults over the years.

Witt, however, would not be around for long to see it. According to Horwitz, Witt had struggled with his health.

"Mr. Witt, who came from a healthy, robust farm family, was broken physically while a mere young man, having served his master, the public," he wrote in his letter. "And the tragic part of it was that when he became full-time social center director he had to resign as a regular teacher and lost all rights and claims to pension, sick and other benefits. By will and economic necessity, Mr. Witt worked like a trojan until his health failed him completely."

In 1931, Witt died and was buried at Wanderers’ Rest cemetery. But his efforts were not soon forgotten.

Post-Witt

Immediately, plans were afoot to raise money for bust in his honor and for a portrait to be painted and presented to his widow, Ida Harwitz Witt. A committee was organized to collect funds for a plaque for the center. Harwitz Witt was named her husband's successor and ran it for 10 years.

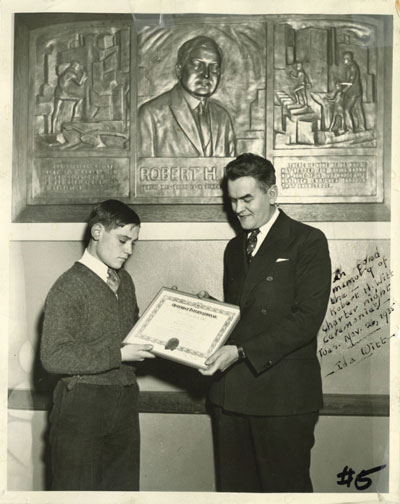

In early 1933, the three-panel plaque, created by George Dietrich of the Layton Art School, was ready, and the newspaper noted, "three panels show a likeness of Mr. Witt and symbolical studies typifying his pioneer work in education through recreation. The pennies of school children and the dollars of former pupils, instructors and friends went into the fund."

The plaque is still mounted on the wall in a prominent location on the first floor of the building. On the left, the image of a man with a plow bears the inscription, "The supreme achievement of a human life is the culture of a soul, is the development of a character."

Opposite, a man can be seen walking children up a staircase. "There is none of us who is not better for having known him, none of us but whose life has been enriched through that knowledge."

In the center, a portrait of Witt, with the dates of his birth (1872) and death (1931) and the inscription, "Robert H. Witt. There was – there is – no finer – manlier man"

For years later, the center held an annual oratory contest that bore Witt’s name, as did the medals presented annually for outstanding community service in the Lapham Park district.

The Alliance era

The activities of the center continued unabated after Witt’s passing right up into the last decade of the 20th century, when it closed and was replaced with Metropolitan High School of the Arts and Technology, which focused on information and communication technology as well as photography, video and audio recording.

In 2009, the program moved to the North Division High School building but it did not last much longer.

In the meantime, Alliance launched in what is now Golda Meir’s upper campus, at that time called the Milwaukee Education Center, in the former Schlitz Brewery, as the first school in the country started with a mission to put a stop to bullying.

When Metro High moved out of the social center – which continued to be called Lapham Park Social Center long after the park was renamed in honor of George Washington Carver in the 1950s – Alliance moved in and it continues to operate there. (The northernmost portion of the park was renamed in 2013 in honor of James Beckum, who founded the Little League program that bears his name.)

"The school opened in 2005 with the goal of providing a safe and accepting environment for all students," reads the program’s website. "The Alliance School is a place where it’s okay to be black, white, LGBTQ, straight, gothic, Buddhist, Christian, or just plain unique!"

The gym looks unchanged from the earliest photos I’ve seen. And when Alliance moved in, teachers found banners from over the many years that the social center operated and they hung them in the gym in celebration of the building’s history.

The former billiards room is now an art classroom, the top floor performance space appears to still have its original stage – and, oddly, an array of taxidermied animal heads. The kitchen is intact and each of the row of drawers of the built-in cabinets has the name of a sport penciled in it. Old ticket booths also survive, though they’re now used as closets.

The basement still has its water-resistant enameled bricks even though the boys and girls shower rooms and adjacent locker rooms have been removed, converted into offices, closets and bathrooms.

And, yes, the tunnel is still there, as is the connection to the Roosevelt heating plant. Like the building itself – now more than a century old – the tunnel still gets a lot of use. As we walk through, I ask the engineer if she ever uses it.

"I come through here every day," she says.

Want more?

Listen to the Urban Spelunking episode on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee.