For decades, passing 3rd and Wells has conjured, for me, the sound of the classic Miles Davis Quintet – featuring John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Paul Chambers, Wynton Kelly and Jimmy Cobb.

This seminal group was booked in March 1959 to play a week-long stint Izzy Pogrob’s Brass Rail, 744 N. 3rd St., and the gig has become legendary among Milwaukee jazz fans. I’d have loved to have been there, if only it had actually happened.

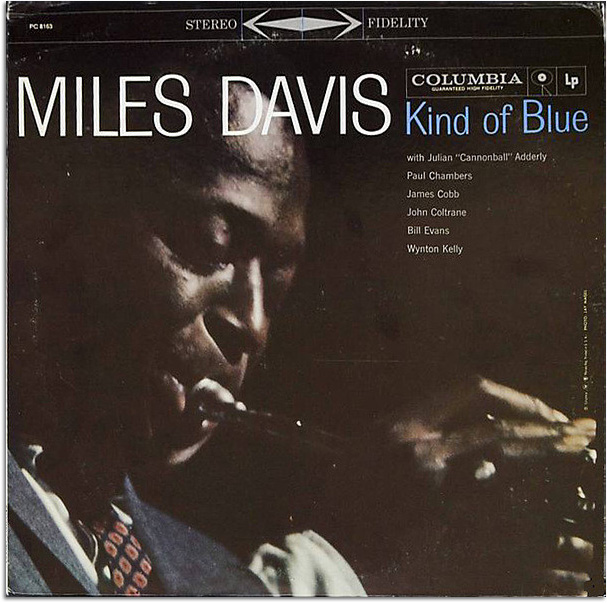

Think of it, Miles, Trane and company in Milwaukee, just a couple weeks after laying down side one of what would be released as "Kind of Blue" the following August, and about a month before recording side two of what is accepted as the greatest jazz album of all time.

But despite a newspaper advertisement that ran on March 23, declaring "OPENING TONIGHT, The Country’s Hottest Jazz Trumpet Player MILES DAVIS and His ALL-STAR QUINTET," the band did, in fact, not open that night, nor perform any other night, either.

Miles and Trane, 1959

It’s hard to say that Miles Davis was at the summit of his career at the dawn of 1959, because the trumpeter’s long career was more Himalayas than Everest – a series of many peaks – but he was certainly flying high, as the ball came down in Times Square to ring in 1959.

In addition to winning prestigious jazz awards, the handsome and dapper Davis was a box office draw – not just among jazz fans – a household name who had earned accolades that included invitations to teach at Harvard and to become musical director for a record label.

Though his most renowned works were still yet to come, Davis had already released a string of classic LPs.

His band was already recognized as something of a jazz university where promising young musicians arrived, only to graduate soon after as icons themselves. At the start of 1959, Davis’ band included not only Trane – who had come and gone from Miles’ company at least once before a few years earlier – but alto saxophone legend Cannonball Adderley, pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb – a hall of fame outfit if there ever was one.

This is the band that was booked to arrive in Milwaukee for a concert on Saturday, March 21 in the auditorium at Merrill Hall on the campus of Milwaukee-Downer College (now University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee).

After a day off, Miles and his "All-Star Quintet" were then to kick-off a week-long engagement at the Brass Rail, 744 N. 3rd St., Downtown.

Izzy & The Brass Rail

Isadore "Izzy" Pogrob opened the legendary Brass Rail in July 1956 next to the Princess Theater, and there was reportedly a secret passage connecting the two places at some point.

Previously the building had served as a tavern, and the Mint Saloon – which occupied it at one point early in the 20th century – was likely a Schlitz tied house, because the brewery owned the building until 1967.

Later, the building housed a string of clothing and shoe stores up until July 1955, when Tutz’s jazz club moved there from its location up the street at 734 N. 3rd St.

In its year-long engagement at 744 N. 3rd, Tutz’s hosted "the Greatest Living White Blues Pianist" Art Hodes, New Orleans trombone legend Kid Ory, Muggsy Spanier, trombonist Jack Teagarden and others. And 1956 looked set to open with a bang at Tutz’s as bookings with JJ Johnson & Kai Winding, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, and the Oscar Peterson Trio were all announced.

But, business must’ve been tight because by May all those engagements had been canceled, due to what co-owner Joseph Alioto called a "lack of response from the public."

For some reason, Pogrob must’ve thought he could make a go of jazz in the same room where Alioto and company failed. And it seemed like he did so for a while. While some say the place was actually owned by the mob, Pogrob made it his home. His brother said Izzy was at the Rail seven days a week.

Musicians felt welcome there and he booked top names like Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughan, Chet Baker, Lionel Hampton, Shelly Manne, Dave Brubeck, Gene Krupa and Teddy Wilson, among others, as well as local talent like Manty Ellis, Bunky Green and a young Al Jarreau.

Pogrob weighed 320 pounds and cut an imposing figure, but he was often remembered by musicians for the way he welcomed them.

Green credits his time at the Rail for his ability to emigrate to the happening New York jazz scene in 1960.

"I was working at the Brass Rail playing strip shows," Green told the Milwaukee Journal later, "and I had just saved up enough money to get away from town. I always believed in planning a little bit, so I took a year and a half to get some money together. Then I just up and left. There was really nothing left for me here."

In spring 1959, Pogrob was apparently losing money at the Brass Rail and decided to bring in strippers. Among them, over the years, was local legend – and tavern owner – Satin Doll, as well as a stripper who reportedly owned a lion that she drove around in her car, the jungle cat chained to the steering column. An ad from 1972, even announces a run by Zana, a fire-eating stripper.

The legendary show that wasn’t

One of the most anticipated gigs Pogrob booked was Miles Davis and his All-Star Quintet in March of 1959. The gig would fall right between the two recording dates that resulted in Davis’ "Kind of Blue" album, arguably the greatest jazz LP of all time.

But it was not to be, though the question why remains a mystery.

There is no doubt that Adderley had been ill around this time and he even took a break from the band for a few months to recuperate. But a Milwaukee Journal notice announcing the same-day cancellation of the Downer College gig claimed that Miles Davis himself was ill and still in New York City.

Davis biographer Ian Carr wrote in his "Miles Davis" The Definitive Biography," that: "Coltrane also fell ill, and although Miles had signed a contract to play a Milwaukee night club, he canceled the booking, thus risking legal proceedings and a fine. This gives some indication of how highly he rated his two saxophonists; if either of them had been fit, he would certainly have fulfilled his part of the contract and played at the club."

The problem is that during the week that the Davis group was slated to play at The Brass Rail, most of its members – Coltrane included – were hale enough to partake in recording sessions in New York City.

Wynton Kelly recorded material with Abbey Lincoln for her "Abbey Is Blue" LP on March 23 and 26, and recorded tracks for the "Much Brass" record with Cannonball’s brother Nat Adderley on March 27.

Trane and Paul Chambers were in Atlantic Studios on March 26 recording first takes of "Naima," "Giant Steps" and "Like Sonny" — tunes that would ultimately end up on Coltrane’s milestone "Giant Steps" LP, albeit from takes recorded at later sessions. (The March 26 sessions later emerged on 1975’s "Alternate Takes" set.)

Milwaukee jazz critic Kevin Lynch has some ideas, too. Miles and company played in New York, Chicago and San Francisco around the same time, he notes.

"They are all larger cities than Milwaukee – San Francisco, scene-wise, for sure – and Miles might have just canceled the Brass Rail date as perhaps as not lucrative enough. He enjoyed having the money for the finer things in life.

"He may also have been prepping for the April 2 (filming of the) TV show (‘The Sound of Miles Davis’ aired on April 11), rehearsing and recording with the Gil Evans Orchestra. Miles perhaps did not inform the Brass Rail in time to cancel the advertisement on the date. It was probably messy."

And, thus, perhaps the most anticipated and fabled jazz gig in Milwaukee never actually happened.

Speaking of messy, less than a year after the Davis’ group’s cancellation at the Brass Rail – for whatever reason – Izzy Pogrob turned up dead in a ditch next to a country road in Mequon, with nine gunshot wounds to the head.

Jazz fizzled at the Brass Rail, which Pogrob’s brother Irvin ran as a strip club until 1968, when it was taken over by Rudoph Porchetta. In the 1970s it morphed into a pizza place – though it served food much earlier – and tavern and finally closed in 1982.

In 1984, according to the Milwaukee Journal, the city’s Redevelopment Authority bought the Brass Rail building from its owner, attorney Joseph Balistrieri, for $125,755 and then purchased the Princess – by then a porn palace – and tore them both down. The idea to build a hotel on the site never materialized and the land remains vacant to this day.

Miles ahead

Unsurprisingly, Miles Davis had been to Milwaukee to perform on other occasions before 1959.

On Nov. 22, 1948, he performed on what the Journal called "an unusual bill at the Pabst Theater," with Max Roach, jazz tenor man Allen Eager – who participated in LSD tests and raced cars (presumably not at the same time) – singer and guitarist Jackie Parris, Baltimore jazz singer Delores Bell and Chicago disk jockey, concert promoter and record label owner Al Benson "and a group of his entertainers."

Most notable on the bill was Billie Holiday, who was making her Milwaukee debut that night.

(It should be noted parenthetically, that there is some doubt cast upon this appearance, too, as Ken Vail, in his book, "Miles’ Diary: The Life of Miles Davis 1947-61," suggests Davis was performing at the Three Deuces club in New York City Nov. 3-24.)

Davis was back in town nine years later – to the month – as part of the Jazz For Moderns Fall Tour that was making its way around the country, with George Shearing’s sextet – which headlined – Gerry Mulligan’s quintet, Chico Hamilton’s quintet, Helen Merrill and the Australian Jazz Quintet. Jazz critic Leonard Feather was the emcee.

But when Davis’ quintet hit the stage at the Auditorium’s Bruce Hall on Nov. 9, 1957, Bobby Jaspar – not Trane – was on tenor. Though Trane had done his first stint with Miles beginning in 1955, the two had parted ways in ‘56 and wouldn’t reunite until 1958.

Express Trane

In the early 1960s, there was a brief glimmer of hope that Trane would arrive in Milwaukee, according to "The John Coltrane Reference," a detailed work compiled by Lewis Porter, Chris DeVito, David Wild, Yasuhiro Fujioka and Wolf Schmaler.

They wrote, "A Milwaukee promoter attempted to engage the John Coltrane Quartet for a theater date in Milwaukee around this time (August 1962), but evidently was unable to do so. There are no listings in the Milwaukee Journal for a Coltrane concert around this time (Aug.-Sept. 1962); Coltrane went to Washington, D.C., immediately after Chicago, so it appears the concert didn’t happen."

The authors quote an article from the September/October 1962 edition of "Jazz Report," that said, "Independent promoter here trying to bring John Coltrane in for a big theater bash after McKies date in Chicago. People here not making room available, some thought of outdoor set but this offers many problems."

Coltrane died of liver cancer in Huntington, New York, on July 17, 1967.

Did Coltrane never play in Milwaukee?

Not so fast.

Like a number of other notable jazz musicians, young John Coltrane got his first real break thanks to bebop trumpet pioneer Dizzy Gillespie, whose band he joined in 1949.

"We went to Milwaukee in January 1950, where we played at the Riverside Theater" wrote Coltrane’s friend, fellow saxophonist and Dizzy Gillespie bandmate Jimmy Heath in his book, "I Walked With Giants: The Autobiography of Jimmy Heath."

"We got into town on the closing night of the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra. Coltrane and I went to the theater because Dorsey was quite a famous alto saxophone player, and they let us backstage because we were opening the next day with Dizzy. Jimmy was so drunk. When you admire a person as a hero, you don’t always realize that they are human. I was a young man and thought Dorsey was larger than life. I had seen both Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey at the Earle Theater (in Philadelphia, Heath’s hometown. -ed.) when I used to go hear the bands. At that point in Milwaukee, I realized that Jimmy Dorsey was an alcoholic, and it was a surprise to me.

"When we opened the next day and played for a week, Paul Gonsalves was on tenor, with Trane and me playing altos. Dizzy had arrangements that featured the tenor, and Trane and I didn’t get many solos during theater performances. If we played a dance, we would have a couple of solos each; for the most part, though, the tenor was featured at theater performances, which were more condensed. This was when I realized that the tenor sound was more important to the audience, more appealing. All the young ladies who came backstage didn’t care about me or Coltrane. They wanted Gonsalves: ‘Where’s Paul? Where’s Paul?’ Paul was the guy. It could have been based on his appearance; he was part Portuguese. It could also have been just the way he sounded – he had this breathy tenor sound that was very beautiful – or simply because he was featured and we weren’t.

"Trane and I eventually switched to tenor because that was the instrument of choice, especially following the war."

Saxophonist Bunky Green remembered seeing one of the performances at the Riverside.

"I saw the Gillespie band in Milwaukee in 1950, playing at a local ballroom," he recalled in a memory shared in J.C. Thomas’ book "Chasin’ the Trane: The Music and Mystique of John Coltrane."

"John Coltrane and Jimmy Heath were the two altoists,but what they did offstage caught my attention more. During intermission, they were standing in a corner, playing Charlie Parker solos note for note. One would play a line, and the other would counter with a complementary line. What they were really doing, I guess, was playing Bird duets with each other."

So, it turns out that while the legendary tenor man John Coltrane never played in Milwaukee, a younger, alto-wielding version did make a stop here almost a decade earlier.