Senators John McCain and Harry Reid don’t agree on much, but they do agree that a presidential pardon for Jack Johnson is way overdue.

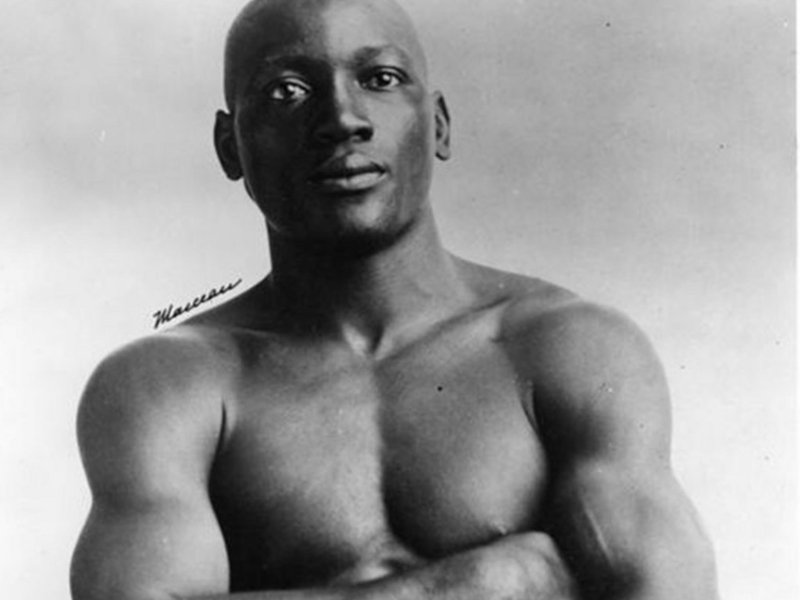

Johnson was the heavyweight champion of the world from 1908 to 1915, a proud black boxer who vanquished every Caucasian challenger put in front of him with such smiling ease, at a time when the servility of black Americans was demanded by white society, that bringing Johnson down became a national obsession.

When it didn’t happen in the ring, in 1912 the federal government charged Johnson, a serial womanizer whose preference for white companions provoked as much outrage as his boxing superiority, with violating the Mann Act prohibiting the transportation of females across interstate lines for "immoral purposes."

Upon his conviction by a jury in Chicago, Johnson fled overseas.

He remained in exile for seven years, and in 1915 lost his championship to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. When Johnson finally returned to the USA in 192, he served a year in the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Johnson had ties to Milwaukee. His conviction was based on the testimony of Belle Schreiber, daughter of a local cop, who met Johnson when she was working as a prostitute in Chicago.

For several years she was one of his "wives," and federal investigators clearly coerced her into serving as their star witness against him.

Johnson boxed at local theaters before and after becoming champion, wrestled here several times in the 1920s and ‘30s, and briefly resided in Milwaukee in 1940, six years before his death in a car crash.

That he was punched below the belt by Uncle Sam has been well established in numerous books, films and documentaries about Johnson.

But on Wednesday, boxing fans McCain and Reid again asked for a full presidential pardon as "an important step in repairing the legacy of this great boxer and a rare opportunity for our government to right a history wrong."

Five years ago a resolution in favor of a pardon passed both houses of Congress, but the Justice Department had better things to do than deal with posthumous pardon requests.

What happened to Johnson was wrong. So was the official ban against black fighters in Wisconsin rings until 1930 because, in the words of state athletic commission chairman Walter Liginger, "Negro boxers have done more to put boxing in disrepute than all the white boxers in the game, and whenever there is a scandal, invariably there is a colored gentleman involved."

It’s sad, too, that the Milwaukee Sentinel once lauded John L. Sullivan, the first modern era heavyweight champion who refused to give deserving contender Peter Jackson a shot at the title because he was black, as a man who "thought too much of himself and the honor which attended his championship to take the chances of wasting it on a colored man," and said, anent Johnson’s marriage to a white woman, "It is not natural that the white and the black should mate, and no black man is entitled to any respect or sympathy who deliberately seeks a white wife."

And that The Milwaukee Journal routinely referred to Johnson as a "dinge."

Should Gov. Scott Walker apologize today for Liginger’s slander? Should the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel print a mea culpa for the racism of its antecedents?

No.

Everybody knows they were wrong then. We can’t change or airbrush history 100 years after the fact, and there are too many current issues demanding public attention to waste time on self-righteous political theater.

Johnson has hardly been under-appreciated. He is in the International Boxing Hall of Fame, and ring historians consider him one of the greatest of all heavyweight champions. He also physically abused the women in his life, and thought traffic regulations were for everybody else.

But if anything his legend has been gilded over the last century, and doesn’t require more polishing by self-serving politicians.

His autobiography is titled, "Jack Johnson Is A Dandy," and there’s no arguing with that. On Sept. 8, 1927, Johnson was arrested in Omaha, Nebraska, along with boxers Young Stribling and Leo Diebel, after the referee stopped the fight between Stribling and Diebel in the sixth round because neither was willing to mix it up.

Johnson’s crime was announcing to the crowd of 5,000 that he could "knock out both Stribling and Diebel in two rounds."

He was 49 at the time, and to anyone who doubts that he could’ve done just as he said, I pardon your ignorance.