Henry Baker lived to fight another day after future heavyweight boxing champion James J. Jeffries figuratively handed him his head in the most important match of Baker's career in 1897.

The mystery is, how did the Milwaukee boxer manage to go on living after the wheels of a freight train lopped Baker's head clean off -- literally -- 11 years later?

Once hailed by the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper as "the coming heavyweight champion," the man known locally as "Heine" Baker had a downtown tavern and was a boxing instructor at the Milwaukee Athletic Society. A stint in the Chicago stockyards accounted for his fighting nickname, "Slaughterhouse" Henry.

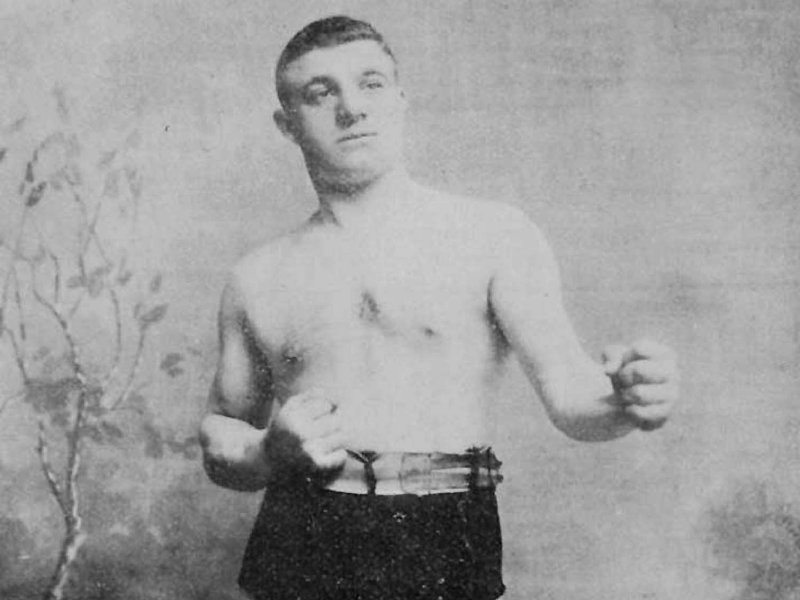

Baker was "a real fighter," recalled Jeffries in his memoirs. "He was built like Tom Sharkey [another rugged 1890s heavyweight], but more smoothly muscled, and his weight, like Tom's, was 185 pounds. He was one of the most confident men I ever saw."

Heine earned his first notoriety in 1894 by whipping Denver Billy Woods in Chicago. A year later, Baker boxed an exhibition match with then-middleweight (and future heavyweight and light heavyweight) champion Bob Fitzsimmons at a Milwaukee theater, and "was not only aggressive all through the bout," reported The Journal, "but his protection was strong and effective."

Real prizefighting was illegal in Wisconsin, and many of Baker's fights were bootleg events. On June 9, 1895, he and Lem McGregor were supposed to fight in some woods south of Milwaukee. When less than $100 was put in the hat passed around by the 60 spectators for the winner's purse, McGregor refused to fight. "Baker called him a coward, but that did not stir his Southern blood to boiling," reported The Evening Wisconsin. A spectator named George Curtis agreed to fight Baker for $50, and was knocked out in four rounds for his trouble.

A month later, just as Baker and a Chicagoan named Michael Brennan squared off in a dance hall on the city's southern outskirts, a posse of county sheriff's deputies busted in and put everyone under arrest for violating the state statute against prizefighting. "Consternation seized the crowd and there was the liveliest kind of a scramble for the freedom of adjacent fields," reported The Evening Wisconsin.

Baker and Brennan were the first ones charged with violating the anti-boxing law in Milwaukee County in eight years. They could have gotten up to five years in jail and a fine of $1,000, but the boxers were fined only $10 each plus court costs.

A week after that, a fight at a North Side Milwaukee tavern on July 22 between Frank Klein and Louis Schmidt ended when Schmidt was knocked out in five rounds. Schmidt died at the scene. Klein was arrested for murder, and Baker, his cornerman in the fight, was also indicted. Heine skipped town, but a week later was arrested in Grand Rapids, Mich. and extradited to Milwaukee. This time the fine was stiffer, and Baker departed Milwaukee for good.

On the West Coast he helped prepare Bob Fitzsimmons for a match against Tom Sharkey in San Francisco. "The fact that Bob Fitzsimmons has selected Henry Baker of this city to assist him in training for his bout with Tom Sharkey goes to show that the Milwaukee boy is well thought of by the middleweight champion," said The Evening Wisconsin. "There has never been a 'Dutchman' who has displayed more gameness in the roped arena than this same Henry Baker."

"Baker Is Expected To Win," proclaimed The Milwaukee Journal hopefully when Heine fought Jeffries in San Francisco on May 18, 1897. It was scheduled for 20 rounds, and "the prediction is freely made by the Chicago sports that if Baker manages to land either glove on Jeffries, the latter's gallop toward the championship will be stopped."

Baker had his moments. He "did some pretty footwork for half a dozen rounds, and once or twice managed to land left and right on the Los Angelan when the latter least expected it," according to the San Francisco Examiner's report of the fight.

Jeffries himself later recalled, "I must say that the stockyards champion gave me good, hard work to do. As soon as we began he rushed at me and swung on my jaw with all his might. It was a great punch. He kept on swinging and tearing at me. He surely was a husky, tough fellow.

"I began nailing him with lefts and rights, and as the fight went along I measured him and knocked him down half a dozen times. In the seventh round, I remember, I hit him so hard that his heels flew up in the air and he turned a complete somersault."

They stopped it in the ninth, after two left hooks from Jeffries made Slaughterhouse Henry woozy as a cow whose next stop is the hamburger factory.

Because the confident Milwaukee fighter had bet his entire end of the purse on himself, he ended up with nothing and had to scrounge money to pay for an expensive oyster dinner he promised friends after the fight.

Baker fought until 1903, and then went to work for the streets department in Kansas City, Mo., and was out of the news until Oct. 10, 1908.

Under the headline "Heine Baker Dead," the Milwaukee Free Press reported, "The headless body of Henry Baker, one of the best known heavyweight boxers in the country at one time, was found on the railroad tracks near the Union depot" in Kansas City. "It is thought he was run over by a Burlington train." The Kansas City Star reported that services were held at Stewart's Chapel a few days later, and that Baker was laid to rest in Union Cemetery. He was 42.

"Baker was a big, good-natured German and he had many friends here," eulogized The Evening Wisconsin. "He was never considered a clever man, but was as strong as a bull and (was) always picked out for the big fellows when they wanted a real try-out."

Apparently Slaughterhouse Henry was stronger than any bull, because he didn't let losing his head keep him from living a very long life.

In April of 1951, a San Francisco Bay area newspaper ran an item announcing a sports program for residents of the Livermore Veterans Home. "Among participants," it said, "will be Sailor Tom Sharkey and his former sparring partner, Henry Baker, who contributed so much to Sharkey's standing as a heavyweight 50 years ago."

Ten years later, another West Coast newspaper reported, "Henry Baker, who was Jim Jeffries' third San Francisco opponent in 1897, died here last week of a kidney ailment. Close friends say he was 91. Baker appeared on the old Orpheum circuit at various times with Jim Jeffries, Jim Corbett and Tom Sharkey."

Jeffries and Sharkey both died in 1953, and haven't been heard from since. They were merely human after all, lacking the true indestructibility that Milwaukee's slaughterhouse champion had, apparently, up the Heine.