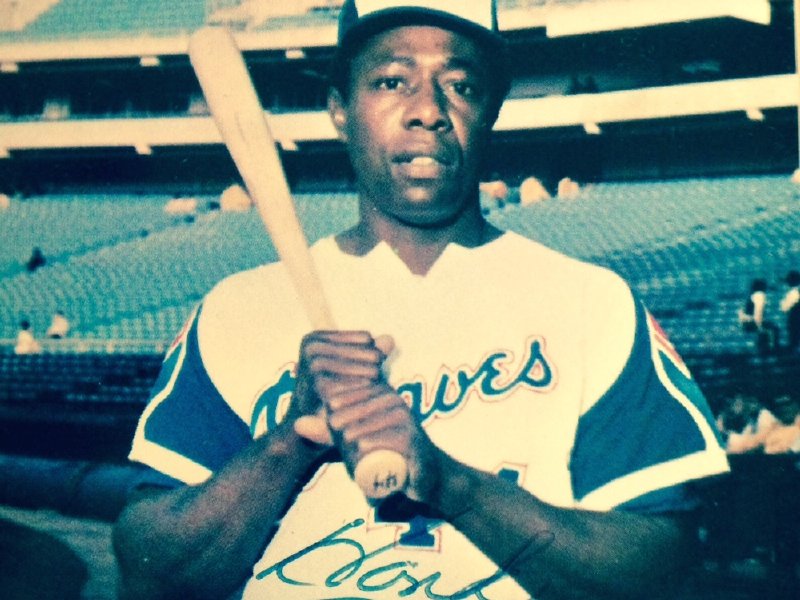

When Atlanta Braves slugger Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run in Atlanta on April 8, 1974, it shook the world and Milwaukee and Wisconsin took real pride in being part of it.

As a 12-year-old baseball fan growing up in Whitefish Bay, Aaron was easily my favorite baseball player, and still is in 2014. Sure, there was early Brewers star Tommy Harper and Robin Yount is a close second to Hank. I'm a huge Gorman Thomas fan and am still pulling for Nyjer Morgan in Cleveland. My close friends know my strange appreciation for more obscure players like Cito Gaston and Dave Kingman.

At the time, I wrote a letter to the Braves supporting Aaron against the racist letters and taunts he received while chasing Babe Ruth's record. I didn't ask for an autograph, but they sent me one anyway. I took my appreciation for Aaron to another level when my wife let us name our second son after him in 1996. Needless to say, we have a nice collection of bobble heads and other Aaron memorabilia, and our Henry was always number 44 on his junior league baseball teams.

Wisconsin and Milwaukee has also honored Aaron with the growing Hank Aaron State Trail linking the far West Side to the lakefront, retiring his number at Miller Park, a Hank Aaron statue at Carson Park in Eau Claire where he played minor league ball, and a wonderful book – "Hank and Me" – written by Milwaukee's Sandy Tolan in 2000. Of course, now in 2014, the Brewers have given us Hank the Dog.

Aaron came to Milwaukee as a major league rookie in 1954 after playing with the Northern League Eau Claire Bears. Before that, Aaron started his professional career in 1951 with the Indianapolis Clowns in the remnants of the old Jim Crow-era Negro Leagues.

The poetic justice of a former Negro League player breaking baseball's most sacred record in the heart of the old South was not lost of Aaron and many others.

So, just think of it now. A quiet, shy but amazingly talented black kid from Mobile, Ala., starts his career in Indianapolis, then Eau Claire and to Milwaukee for the glory years of the Milwaukee Braves. But, those years in Milwaukee from 1954 to 1965 were also the peak of the Civil Rights movement all around this country.

So, besides the statues, trails, plaques and dogs, just how did Hank Aaron change our area beyond his feats on the baseball field?

First, let's be honest. It's easy for anyone but the most hateful racist to appreciate black athletes like Hank Aaron. After his walk-off home run won the 1957 National League pennant for the Braves, he became an instant Wisconsin sports legend.

Second, while Aaron was, and still is, quiet and humble about his personal accomplishments, he always chose the best words and appropriate battles to fight racial injustice in sports and elsewhere. He remains critical of MLB for having only about 7 percent African-American players and a handful of managers, coaches and executives.

Third, consider that Aaron wasn't the only minority member of the Milwaukee Braves embraced by fans in our area back in the 1950s and '60s. Billy Bruton, Wes Covington, Felix Mantilla and Hank's brother Tommie were as popular as many of the other Braves in those days. Again, they were talented and contributing players, but were never overshadowed by Aaron, who always put the team above himself.

Finally, Aaron was a pioneer for other black athletes who embraced Milwaukee and Wisconsin beyond their playing days and continue to thrive here. Packers Hall of Famer Willie Davis is as tough in the board room as he was on the field, Junior Bridgeman might use his business acumen to help keep the Bucks here, and others like Bob Lanier and Larry Hisle have made community impact behind the scenes. Some also might remember another Mike Morgan (Wisconsin and NFL running back) who was a long-time and well-liked Wisconsin government official.

So, Milwaukee and Wisconsin needs to appreciate how blessed we are to be indelibly linked to the professional and personal achievements of Hank Aaron just as much as he appreciates us.