If you like this article, read more about Milwaukee-area history and architecture in the hundreds of other similar articles in the Urban Spelunking series here.

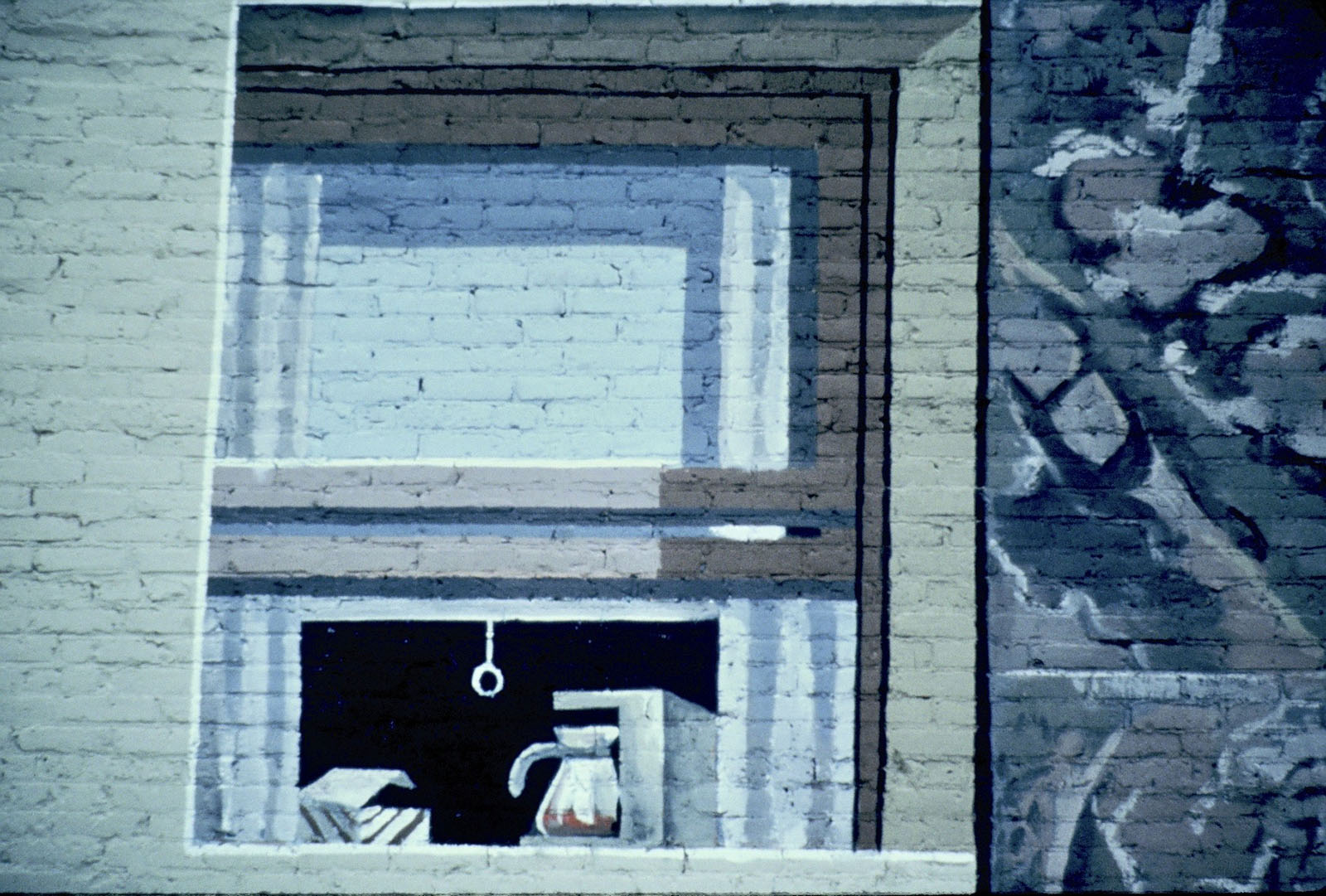

Though it’s only been mentioned in passing during the exciting renovation of the 1930 Warner Grand Theater, 212 W. Wisconsin Ave., into the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra’s new home and performance venue, the 1981 mural on the east side of the building’s tower will get a much-needed facelift as part of the massive project.

According to a symphony spokesperson, though there is no solid timeline for the touch-up on the side of the Bradley Symphony Center, it is still part of the plan with the MSO consulting with Yonkers, New York-based artist Richard Haas, the Wisconsin native that created the mural.

The painting is a soaring trompe l’oeil illusionist work – roughly 120 by 75 feet – that appears to be a series of windows and a large central faux glass panel that reflects buildings no longer standing along Wisconsin Avenue, like the Pabst Building and the former Lake Front Depot, as well as some that are, like the former Gimbels building.

This and the other 1981 photos in the article are from Haas' own collection, shared with kind permission.

"It was done during a time when they were attempting to renew the west side of Wisconsin Avenue, that is the side west of the Milwaukee River," Haas told me via email. "They were also doing the (Grand Avenue) shopping mall in the Plankinton building which was adjacent.

"The work itself came about I think primarily because my name was well-known across the country and to some degree internationally at that time and even Russell Bowman who was the (chief curator) of the Milwaukee Art Museum at the time also knew about it and I think helped it along."

Born in 1936 in Spring Green, where his father was a butcher, Haas moved to Milwaukee at age 7. After attending grade school in West Allis and graduating from Pius XI High School, he studied at UW-Milwaukee, where he said faculty member Joseph Friebert had been a great influence. After teaching art at Lincoln High School from 1959 until 1961, he moved to Minneapolis to earn his MFA at the University of Minnesota.

"Since then I was a professor for four years at Michigan State University and then I moved to New York in 1968, living the first 11 years in SoHo and since then in the city of Yonkers with a studio in Manhattan, also teaching for 11 years at Bennington College in Vermont and two years at School for Visual Arts in New York."

So varied is Haas’ experience in academia and in the creation and execution of artwork, that he initially neglected to share this:

"I also forgot to mention that in 1955 and ‘56, I returned to Spring Green to assist my great uncle in working for Frank Lloyd Wright where he was Wright’s master stone mason."

He recalls that his relationship with Milwaukee made the work a little easier for him than similar ones he’s created around the world in cities like Manhattan, Brooklyn, Munich, Chicago, Des Moines, Galveston, Boston, Madison and beyond.

"I knew a lot about the city and it’s history and so this was an easy one that required less research than it does when I go to a foreign city where I know so much less," Haas told me. "I walked on Wisconsin Avenue and I remember the buildings that lined that street all the way to the lake including the original Pabst Building and also the Northwestern Railway Station. Yes, I even visited Santa on the top floor of the old Gimbels department store."

Before returning to Milwaukee to create the mural, Haas gained much attention for a similar work installed in New York’s Times Square, where he painted a trompe l’oeil "reflection" of the wedge-shaped early 20th century Times Tower newspaper headquarters onto the windowless side of a 10-story building.

"(It) is so persuasive in its realism that many New Yorkers stroll past it without ever realizing they are seeing an illusion," wrote Milwaukee art critic and gallery owner Dean Jensen in July 1981.

The idea for these murals that reflect demolished skyline features came from seeing works by Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi who in the 19th century attempted to recreate ancient Roman cityscapes in his etchings by studying the surviving ruins in Rome.

"Partly, the mural can be seen as a reflection of some of my memories of the city," Haas told Jensen in 1981. "Memories of things that were grand, but are now gone. I remember the Pabst Building as being very grand, for example, but now it has been taken from the city. It is the kind of thing that happens in cities that maybe shouldn’t happen."

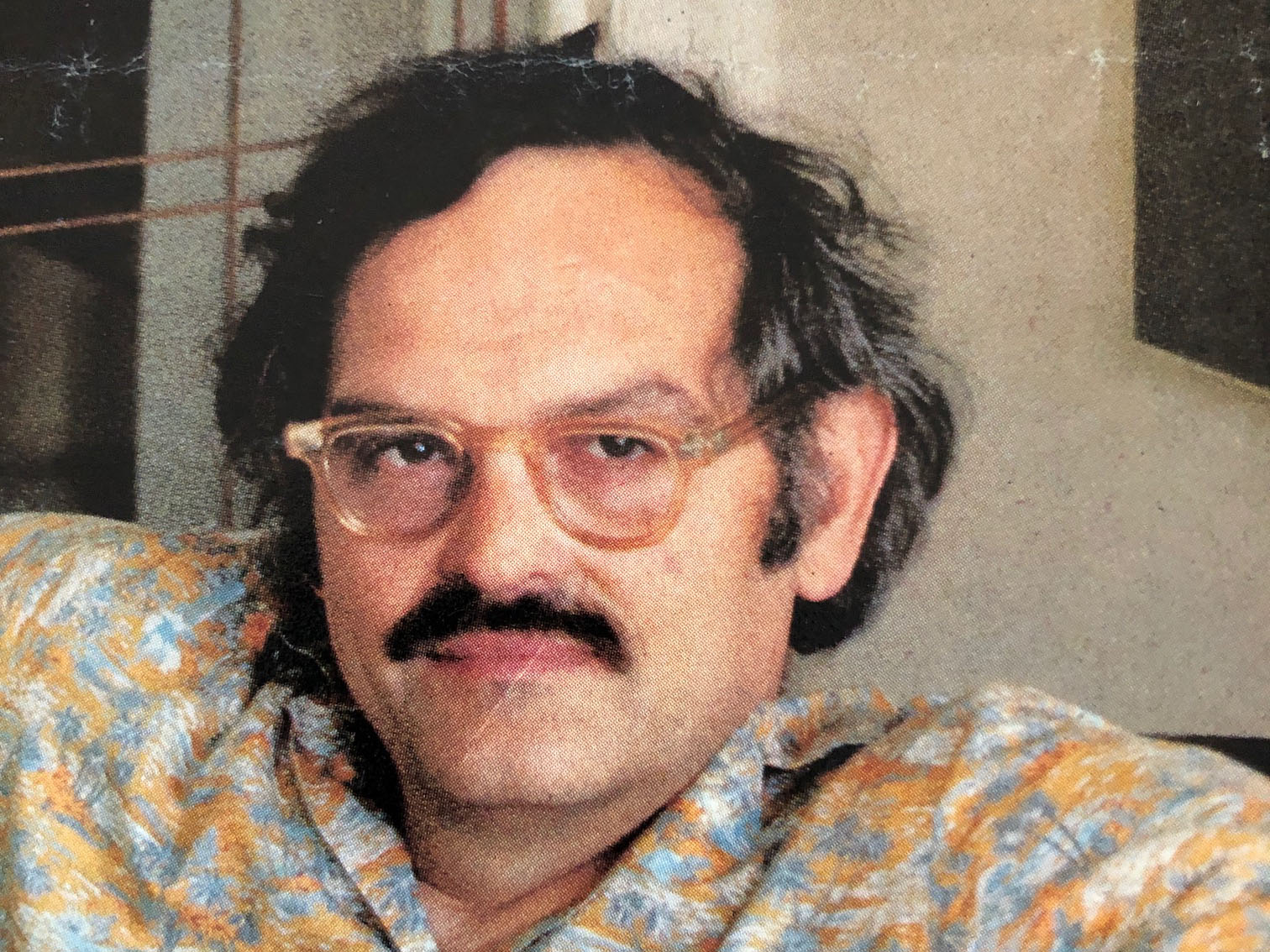

Richard Haas in a 1981 photo. (PHOTO: Courtesy of Richard Haas)

Jensen wrote that in the Milwaukee Sentinel upon the announcement of Haas’ Milwaukee mural, which was organized by the Milwaukee Redevelopment Corp. and funded with $40,000 from the Friends of Art of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Stiemke Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Wisconsin Arts Board, the Marcus Corporation, First Bank Milwaukee and the Rouse Co., which developed the Grand Avenue Mall.

As was typically the case, Haas drew a maquette of the work at a small scale, and the painters at Evergreene Painting Studio – founder Jeff Greene, Terry Vanderwell and Tom Edwards – scaled it up to fit the space.

Greene, who earned his BFA at the Art Institute of Chicago and still operates EverGreene in New York City, has served as president of the National Society of Mural Painters.

"I have worked with others over time, but they have probably been the most often used group," said Haas. "The maquette, which is now in the possession of the Milwaukee Art Museum, was done as a half-inch to one-foot drawing which was followed carefully by the painters. I have always employed this method in one form or another in the works I have done.

"Even when I was much younger and I could climb those ladders and those scaffolds, I chose to do it that way. Today it would be ridiculous for me even to try."

Greene said at the time that the paint used was a special mineral-based one manufactured by Keim in Germany that was especially wind, sun and moisture resistant. He said it dried almost like plaster and could be expected to endure for at least a decade before any restoration work would be required and that the hues would remain colorfast for at least a century.

Greene, Vanderwell and Edwards began work in the first week of September and by the end of the month, the Sentinel noted that the three could be seen on the job, "from sunup to sundown."

Haas visited the site to check progress during the third week of September.

"I certainly remember working on the Haas mural vividly," says Jeff Greene. "What I remember most was that I moved my young family out to spend the summer on Lake Michigan while I shuttled between two large Haas murals that I was painting that summer. (The other was in Homewood, Illinois.) It was a glorious time!

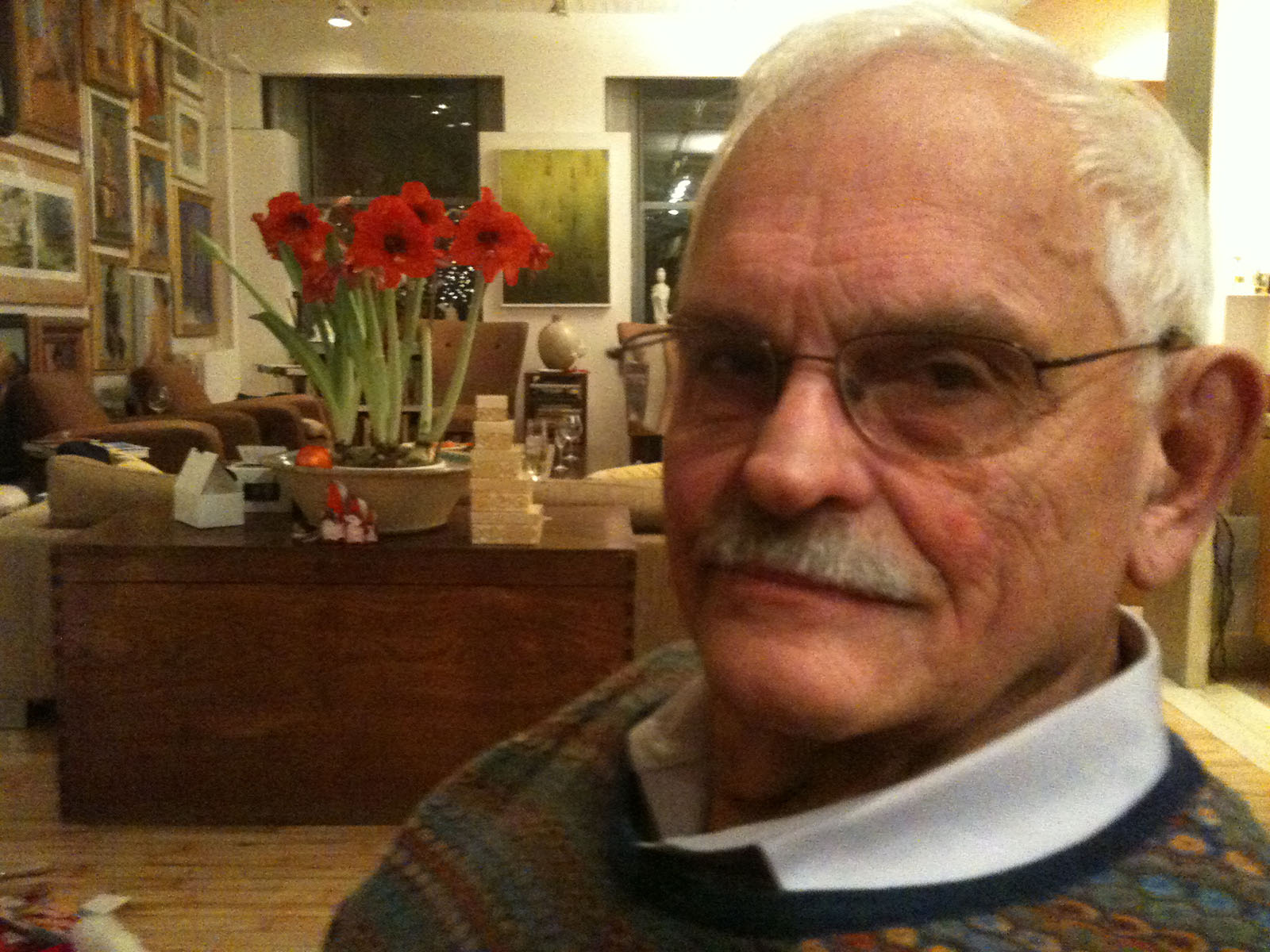

"Terry Vanderwell ... is still working for me now 40 years later! He runs my studio in Chicago. Both he and I are still painting murals, including the occasional mural for Haas who is still active at 83. I have lost touch with Tom Edwards, but I think he still lives in Rockford, although I don’t believe he has painted any murals in quite some time."

Richard Haas today. (PHOTO: Richard Haas)

Creating a monumental work at the intersection of 2nd and Wisconsin was a satisfying moment, Haas told Jensen at the time, because 28 years earlier, a 17-year-old Haas "tried to make his mark on the same site," working as a salesman at Mailing Shoe Store across the street.

"It was my first job and it was a disaster," he told Jensen. "I hated the job and quit after three months."

Looking out a fifth-floor window at the mural being executed, he told Jensen he was confident "that this time he would leave a lasting mark" at 2nd and Wisconsin.

By mid-October, the work was complete and a grand unveiling was set for Wednesday, Oct. 14 at 5:30 p.m. at the bank building across 2nd Street, which offered (as it does now, even though it’s been remodeled as a hotel) a stellar view of the mural.

"By creating illusions of grand old buildings that were once in the cities and then were demolished in the name of progress or urban redevelopment, (Haas) wants people to remember things as they used to be," Greene – who Haas said has expressed interest in doing the touch-up work – told the Sentinel’s Jensen. "Maybe that way, people will think twice before tearing down the next building."

Some were skeptical, like one James Rubin, who wrote a letter to the editor of the Journal, saying, "I sincerely hope that we can now move ahead with the demolition of the few remaining architectural treasures in Downtown Milwaukee, knowing that with artists like Richard Haas, they will not be lost forever."

But, the mural did affect the way some folks looked at Milwaukee’ vintage building stock.

In 1982, outgoing Rep. Henry Reuss, who had been instrumental in saving the German-English Academy, Blatz Brewery and other historic buildings, gazed at the mural while talking to a reporter and said, "It’s too bad we didn’t do something to save those."

That same year, the mural won an award from the Milwaukee Arts Commission.

"I have always focused on several key things," Haas told me recently. "Number one: The building and the environment where the work stands would strongly influence the nature of my work. Number two: A close and logical connection to the actual building where the work is being attached would lead to a design that was carefully woven into or onto that structure. And number three: There was always an attempt to tell more of a story than simply replication of architectural features."

Haas said that while some have suggested that the touch-up work include "updating the reflections," he’s not in favor of that.

"That that would miss the basic nature of the piece in many ways," he said. "It is, after all, a reflection of memory not a reflection of the city as you see it to today. What I was most interested in was to create a ‘reflection as memory.'

"This was not a new idea for me but it was one of the more interesting ways in which I approached that concept. Not only did I remember the old Pabst Building, but when it was torn down, my nephew managed to remove an original piece of the arch and I have it in front of my house in Yonkers."

Like an architect whose work has met the deadly punch of the wrecking ball, Haas has seen some of his many outdoor works vanish.

"I think over 60 percent of the outdoor and indoor works that I have done have been lost," said Haas, who was commissioned to create a series of works for the First Wisconsin Center (now the U.S. Bank Center) that were never installed.

"It is not as well-known but more than 50 percent of my public work is indoors and it is done in state office buildings, libraries, performing arts centers, etc., around the country."

Like the MSO, Haas doesn’t have a timeline for the refresh of his Milwaukee mural.

"As of this time, I have no idea when whether and how the work will be completed since Mr. Marcus, who is going to pay for it, has backed off understandably and unfortunately at this time since there is no activity in the theater business due to the pandemic.

"I don’t know how and when the painting will be done, but it is absolutely necessary if the work is going to continue to exist."

Greene says that the MSO contacted him about doing the restoration work – which would be the first undertaking in the mural's nearly 40-year history – and he hopes to come to Milwaukee to do it.

"Due to the COVID, those plans have been put on hold," Greene says. "I do hope that once things get back to some semblance of ‘normal’ that the powers that be will reconsider that prospect."

Greene says his family would again take advantage of a summer on the lake, if possible.

"My son, who is now almost 40," says Greene, "has expressed an interest in doing the same with his young family if the project were to move forward."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.