Saint Paul Avenue in the Menomonee Valley is having a bit of a moment these days, with a variety of businesses taking up residence on what was once an industrial corridor with little reason to stop, unless you were driving a semi delivering goods.

Of course, there have been exceptions, like Sobelman’s bar and restaurant, BBC Lighting and House of Stone, but now you can add Third Space Brewing, the offices of Plum Media and Christopher Kidd & Associates architects, Brew City CrossFit, the Riverwiew Antique Market, Bachman Furniture and others.

There are so many art- and design-focused businesses here now that the strip has been rebranded the West St. Paul Avenue Design District.

And one of the leading lights in the district is Guardian Fine Art Services, which – along with its own The Warehouse art museum, which shows pieces from the owners' own collection of around 5,000 works – occupies a nearly 100-year-old five-story building at 1635 W. St. Paul Ave.

(PHOTOS: Guardian Fine Art Services)

"The street has really come alive," says owner John Shannon, a La Crosse native. "It's wonderful."

The stretch was added to the Wisconsin and National Register of Historic Places as the 22-building St. Paul Avenue Historic District.

Other than the first-floor art gallery – which recently opened a new show called "On the Nature of Wisconsin," that runs through March 20 – the bulk of the building is filled with secure and temperature- and humidity-controlled storage for fine art and collectibles.

The building is so secure that it is even a TSA-approved Indirect Air Carrier representative, and that’s all I’m going to say about that.

"We talk about artwork, and that's the primary focus of our business," says Shannon, who is married to artist Jan Serr. "But it's any tangible valuable: antiques, firearms. We have a collection of rock and roll posters here. The person who brought them in said they were printed on really good paper. He wants the work here. It's going to last longer here. The longer it lasts the more valuable it is.

"It's a very interesting business. We have carpets. We have musical instruments."

There is also an on-site wood shop in which a staff carpenter builds frames for the gallery, furniture for the building and, often, extremely specialized shipping crates to help valuable artwork get from one place to another in perfect condition.

"The business includes storage," says Registrar Katie Steffan. "It includes installation, transportation – all of the stuff that you would expect if you had high-end art collection and needed to store it. Sometimes we're contracted by other companies to build crates for their clients because they don't offer that kind of service."

According to Shannon and Steffan, Guardian clients range from individuals to estate attorneys to businesses, including art galleries and auction houses, to institutions, including art museums whose own storage areas are overflowing. Often, artwork that is part of a traveling exhibition spends some layover time in a facility like this, too.

One of the objects stored here – and the only one I was allowed to mention (but still not photograph) – is the world’s largest piece of Pop Art: Robert Indiana’s basketball floor for the MECCA Arena.

There are some objects that are no-nos, however.

"Federal law prohibits us from taking some things," says Steffan, "if it's stolen, if it's certain types of ivory, things like that, anything that would be dangerous to somebody, like a health hazard, or infested, or anything like that we can't take. Also silver nitrate film. We can't take that because of how flammable it is.

"Most people who are storing here, it's usually high-value art. They really love the pieces. They're not trying to do anything nefarious by putting it here. They just need a place to park it for a little bit."

There are basically two kinds of storage offered at Guardian: one is managed by the staff (pictured above) and the other is not, but can be (pictured below).

While I wasn't allowed to see inside any actual storage units, there is a showroom that has recreations of each type of storage available.

"Imagine you're walking into a warehouse," says Steffan. "You see things on shelves. That's the area that is charged by cubic foot and that myself and my collection staff manage. Then, this is one of those private vaults (photo just above). A client rents this square footage at flat rate every month, and within reason, they can place whatever they want.

"By in large, the clients who are renting these spaces are (also) having us do all of the collection management. But they could come here if they wanted to."

It’s pretty amazing to see a place like this with its backup generators, high-tech security systems, staff that’s worked in galleries, museums and other art institutions, and the constant 70-degree temperature and 50-percent humidity.

All of that is what clients pay for.

That and the solidity of a building that was built like a bunker with impressive reinforced concrete columns and brick exterior walls. There’s a reason it was declared a fallout shelter decades ago. It’s the kind of place you want to hide out if there’s a natural or man-made disaster.

The place – designed as a warehouse, shipping facilities and offices for a company that sold plumbing fixtures – was built that way to handle the weight of the countless sinks, toilets and other inventory kept on hand.

On the 1894 Sanborn fire insurance map, the southeast corner of 17th and St. Paul is shown as mostly vacant save for an 88-foot tall storage elevator with a capacity to hold 90,000 bushels of fuel coal – presumably for steam locomotives, since it’s alongside the tracks and the name Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad is noted there on the map – with a lumber shed nearby.

Two years later, J. G. Wagner, of his eponymous bridge-building company, tapped architect Charles Kirchhoff to design a $3,000 brick office building on the site and in 1898 Wagner added a new lumber shed and quickly expanded it later in the year.

The building required a lot of cleaning out when Shannon bought it.

(PHOTO: Guardian Fine Art Services)

In 1900 – tapping into the consolidation zeitgeist of the era – Wagner was among the 28 steel and bridge companies that banded together as the American Bridge Company in a consolidation sparked by JP Morgan and Company.

Immediately afterward, the monster new company began to centralize its production and modernize old factories, and it appears to have halted production on St. Paul Avenue.

In 1903 the National Blower Company put an addition on the building, which it appears to have been leasing, because by 1910, American Bridge Company is still listed as the owner of the factory, which was not in operation at the time.

By the early 1920s, this became moot as the Pittsburgh-based Standard Sanitary Supply Company, which had showrooms and warehouses dotted all around the country, outgrew its showroom at 426 Broadway in Downtown Milwaukee.

By the early 1920s, this became moot as the Pittsburgh-based Standard Sanitary Supply Company, which had showrooms and warehouses dotted all around the country, outgrew its showroom at 426 Broadway in Downtown Milwaukee.

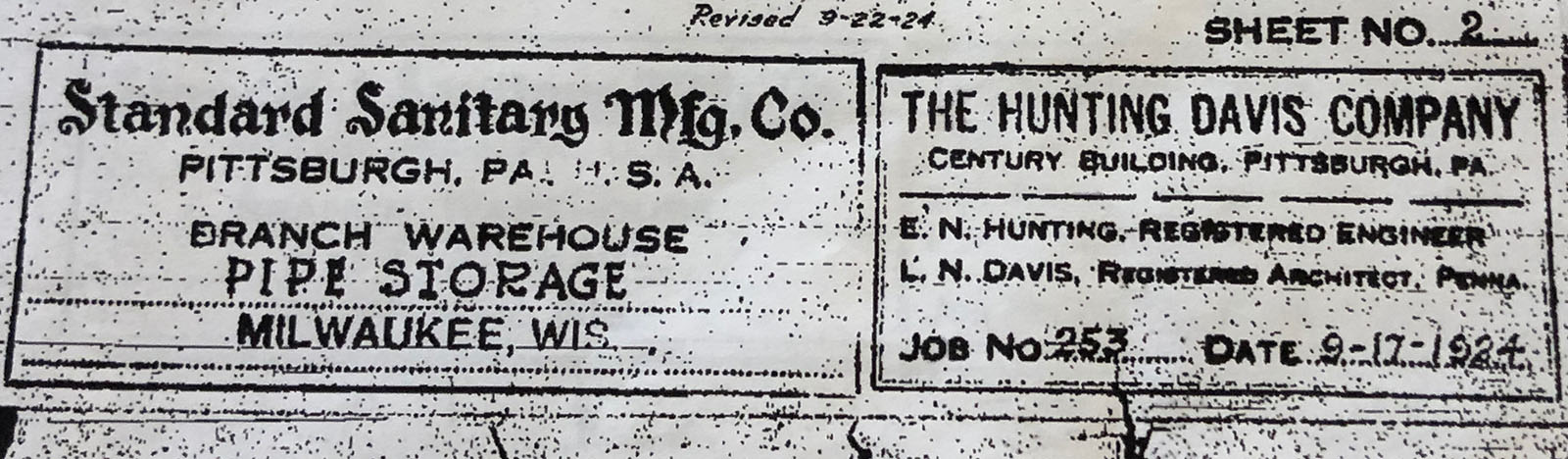

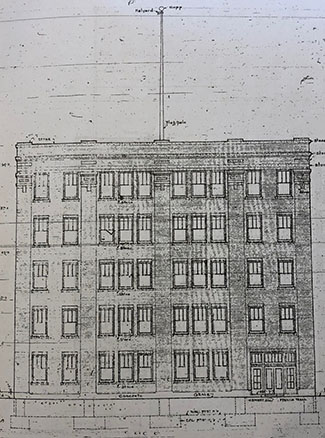

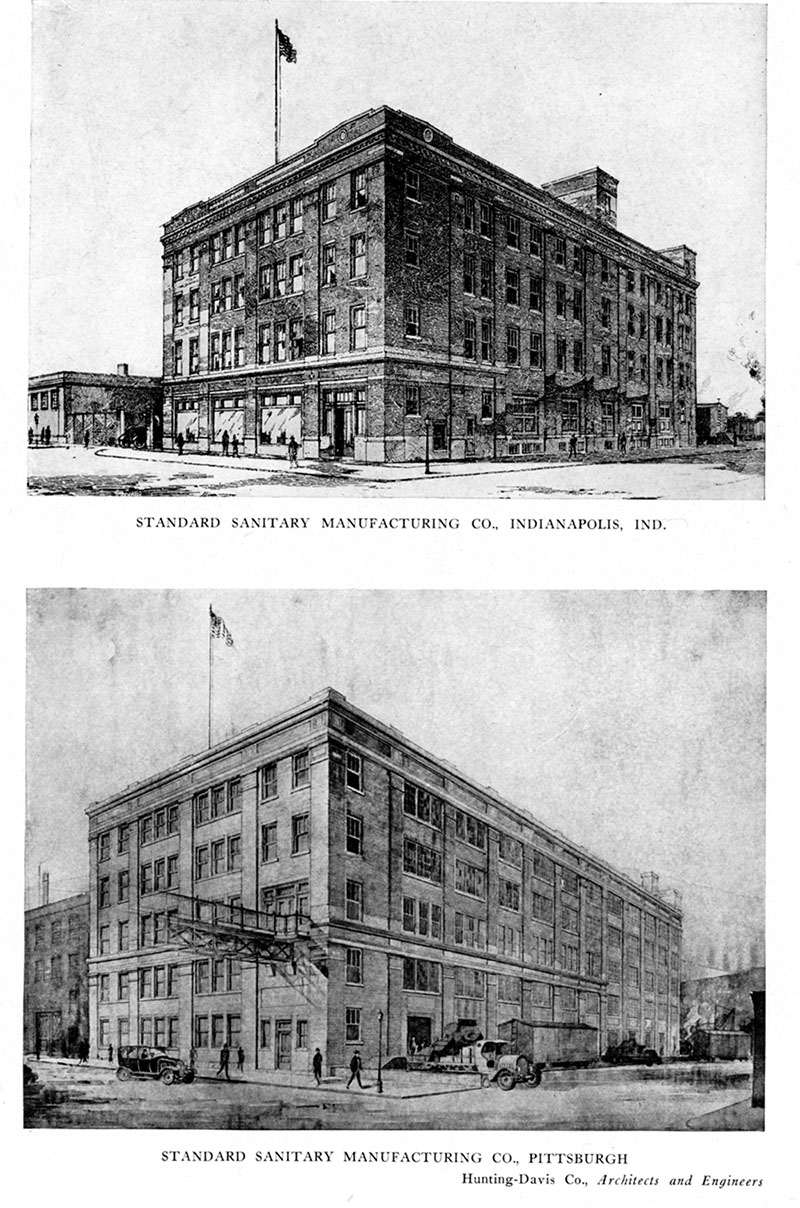

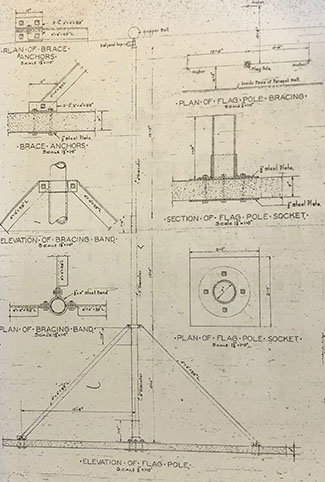

It bought the site and razed the existing structures and in 1924 built the current building, designed by Pittsburgh’s Hunting Davis Co.

The Milwaukee building was similar to another one that the same architect designed for the company in Indianapolis and a third similar, but larger, building was drawn for Standard Sanitary Supply in its hometown. The site of that building, now razed, sits beneath the Steelers' Heinz Field. Perhaps there were still others.

Two buildings of similar scale but different designs were also erected by the company in Louisville.

(PHOTO: Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University Architecture Archives)

Such large and expensive buildings – Milwaukee's is just a tad over 71,000 square feet and cost $350,000 – suggests that business was good in Milwaukee and the rest of the Midwest.

Such large and expensive buildings – Milwaukee's is just a tad over 71,000 square feet and cost $350,000 – suggests that business was good in Milwaukee and the rest of the Midwest.

"It definitely speaks to the investment that East Coast companies were making in Midwestern cities like Milwaukee at that time," says Shannon.

The same year, the company also erected a one-story pipe storage warehouse that was later used as a garage. The building still stands, but Shannon has yet to take on the project of renovating it.

In 1929, Standard Sanitary merged with the American Radiator Company to create the American Radiator and Standard Sanitary Corporation, which continued to own and occupy the building (in later years as AmStan) until 1970, when it was sold to Menomonee Valley enameling giant Geuder, Paschke & Frey (which you can read more about here).

In 1984, it was sold to the Monitor Corp, four years later to Ware Investments and in 2007 to Donald and Virginia Read and was home to a variety of tenants across those years, including Economy Packaging Co., General Press Fabricators and Wisconsin Fire Protection Inc.

Shannon and Serr bought it in 2014 and set to work converting it into Guardian, including remediating the soil and tearing a series of collapsing loading docks off the east side of the building and replacing them with a modern addition that includes a dock and an ADA-accessible ramp into the main entrance.

"This really is a perfect building for what we're doing," says Shannon, "and then, we made it even a little bit better by adding on and creating some modern features for it."

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lived until he was 17, Bobby received his BA-Mass Communications from UWM in 1989 and has lived in Walker's Point, Bay View, Enderis Park, South Milwaukee and on the East Side.

He has published three non-fiction books in Italy – including one about an event in Milwaukee history, which was published in the U.S. in autumn 2010. Four more books, all about Milwaukee, have been published by The History Press.

With his most recent band, The Yell Leaders, Bobby released four LPs and had a songs featured in episodes of TV's "Party of Five" and "Dawson's Creek," and films in Japan, South America and the U.S. The Yell Leaders were named the best unsigned band in their region by VH-1 as part of its Rock Across America 1998 Tour. Most recently, the band contributed tracks to a UK vinyl/CD tribute to the Redskins and collaborated on a track with Italian novelist Enrico Remmert.

He's produced three installments of the "OMCD" series of local music compilations for OnMilwaukee.com and in 2007 produced a CD of Italian music and poetry.

In 2005, he was awarded the City of Asti's (Italy) Journalism Prize for his work focusing on that area. He has also won awards from the Milwaukee Press Club.

He has be heard on 88Nine Radio Milwaukee talking about his "Urban Spelunking" series of stories, in that station's most popular podcast.