This year, PrideFest and the Milwaukee Pride Parade were sadly cancelled for the first time. While many lamented the cancellations on social media, new organizers stepped into the silence to make some noise.

PrideFest 2019 honored the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising with a revolutionary call to action: "RISE!" And this year, the community really stepped forward and redefined what it meant to RISE. On Sunday, June 7, over one thousand marched through Walker’s Point and the Historic Third Ward for the March with PRIDE for #BlackLivesMatter. Elevating the unique voices, experiences and talents of the local African-American LGBTQ community, the march blended pride messaging with the demand for justice and change.

(PHOTO: Cormac Kehoe)

(PHOTO: Cormac Kehoe)

This was not your usual pride parade. This was an emotionally-charged movement, harkening back to the earliest days of gay pride, where marches were considered both a political expression and a social disruption. Truly, "pride" hadn’t looked anything like this in decades, and perhaps never before in some of the marchers’ lifetimes.

The March for Pride has its spiritual roots in the 1st Annual Pride March and Rally of June 17, 1989, where over 1,000 gathered in Cathedral Square to express their anger about inequalities, their fears about the raging AIDS epidemic and their rage against a government that didn’t care. The march has long been considered not only the largest LGBTQ protest in Milwaukee history, but the ignition of the modern pride movement. Milwaukee’s rainbow crosswalks, which outline the route of the March along Wells Street, were dedicated in 2018 to all who participated.

The Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project, born at PrideFest in 1995, has long been tracking the timeline of Wisconsin pride celebrations as well as the unique history of Milwaukee Pride, Inc. For 30-plus years, we’ve considered Pride Week 1988, hosted by the Milwaukee Lesbian Gay Pride Committee, to be the birthplace of today’s PrideFest.

So, imagine our surprise when we discovered an interim series of Milwaukee pride festivals that almost nobody remembers – and, looking back, we can barely believe ever actually existed.

Secret origins

During a May 6, 2011 interview from the Milwaukee Transgender Oral History Project, Dr. Brice Smith uncovered some hidden history with Josie Carter and Jamie Gays.

BS: Have you gone to PrideFest?

JG: Oh yes.

JC: Oh yeah.

JG: I was in the first PrideFest. We had it at Juneau Park.

JC: When it first started.

JC: No no no no, the first one, in Oak Creek.

JG: Oh yeah. Oak Creek, yeah.

JC: Way down in Oak Creek where we got raided. By the bikers, remember that?

The first PrideFest?

In Oak Creek?

Well, I definitely didn’t remember that. As someone who grew up in Oak Creek, when it was still a farm town, I might remember a PrideFest happening out there before 1988, and especially one that was raided by bikers. I was on the Pride board for ten years – heck, I even wrote a book about LGBT Milwaukee – and still I knew nothing about this. Nobody I asked about this mysterious "first PrideFest" knew anything about it either. Unfortunately, Josie left us in 2014, and Jamie is unavailable to ask.

What in the world were they talking about? Sure, we’d heard passing mentions of "the first PrideFest happening in a parking lot behind a bar" in the History of Gay Wisconsin group. But this mention made it sound like more than just a parking lot party.

So, naturally, I had to dive in.

Research and discovery

In August 1961, a steamy series of bar fights put Milwaukee on the map of gay uprisings. The Black Nite Brawl revealed that gay people existed in Milwaukee, in numbers large enough to defend themselves and their territory when challenged. After a lifetime in the shadows, gay people saw the Black Nite as a turning point, and the community became braver and bolder. One might even call it the birthplace of Milwaukee pride.

However, pride events didn’t flourish quite as quickly in Milwaukee as they did in Los Angeles or New York, but relentless efforts were made throughout the 1970s. On Sept. 6, 1971, Chuckie Betz and the Gay Liberation Front appeared in a Labor Day parade protesting the Vietnam War. Thirty to forty men and women marched arm in arm, but only Chuckie, and his fabulous genderqueer look, made the front page of the Milwaukee Journal that day.

Gay People’s Union hosted the Midwest Homophile Conference at the Marc Plaza in April 1972, which brought esteemed activists Dr. Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings and Troy Perry to Milwaukee for the first time. Presumably, this marquee event consumed time, resources and finances, as there was no pride event in 1972.

On June 29, 1973, Gay People’s Union launched Gay Pride Week, which includes baseball games, dances, rallies, a potluck dinner, a "Gay In" at Juneau Park and a picnic in Estabrook Park. The events were so successful that GPU sponsored a Mardi Gras Ball at the Performing Arts Center on Feb. 9, 1974. Out comedian and actor Michael Greer welcomed 350 participants to the event, then considered the largest gathering of gay men in Milwaukee history. The event received live coverage on WTMJ4 and a next-day spot in the Milwaukee Journal.

Gay pride events ebbed and flowed throughout the 1970s. The Chicago Pride Parade was bigger, more outrageous and more exciting, so many Milwaukeeans made it an annual tradition. Gay People’s Union had sizeable contingents in 1978 and 1979, which got people thinking about hometown events for 1980.

On June 28, 1980, a small pride parade marched from Juneau Park west to MacArthur Square, where a rally awaited. Ambitious CPU organizers also hosted a street party outside the Factory Bar (158 N. Broadway), a film festival, a talent show, a Town Hall meeting, a visual arts show at UWM, a potluck dinner at Mitchell Park, an Entertainer’s Club performance of "Hello Dolly" and a charter bus to the Chicago Pride Parade. Student organizers were egged in the UWM Union during their show.

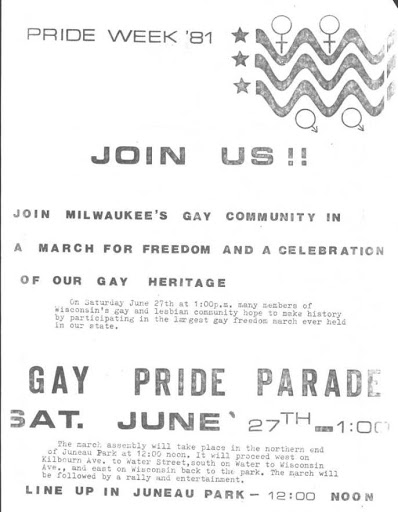

Another parade and rally was planned on June 27, 1981. "Many members of Wisconsin’s gay and lesbian community hope to make history by participating in the largest gay freedom march ever held in our state," read the parade manifesto. However, the 1981 parade seems to have been a bust. Milwaukee supported the Chicago Pride Parade – with larger and larger delegations every year – but the "Gay Rights State" didn’t host any local pride events in 1982. It’s not clear why, but Gay People’s Union seemed to have given up.

A frightening wave of nationwide pipe bombs didn’t inspire festivities. Twenty-one bombs were found in three states, including two that exploded near Third and State and one in the Civic Center Plaza parking garage. Five bombs exploded in Chicago, and six more were found in La Crosse. The "North Central Gay Task Force" took credit for the explosions, claiming retaliation for police brutality and oppression. Eventually, it was discovered that no such group existed, and the bombs were the work of a single individual. After a bomb went off in his car in Mason City, Iowa, he was apprehended, hospitalized and sentenced to 18 months in jail.

"No one, from anywhere in the state, has ever heard of this organization," wrote Ron Geiman, publisher of In Step Magazine. "I believe it’s the work of a homophobic/severely closeted individual who believes (in his distorted mind) that he’s doing us a favor."

At the same time, the menace of AIDS began to loom over the Midwest. "AIDS. It’s not just for the fashionable coasts anymore. It’s here. And it’s real," reads an ominous ad from the era. Between 1979 and 1983, 3,000 cases were reported in the U.S. and 1,900 patients had already died. These numbers would quadruple by 1985, when the Milwaukee AIDS Project formed as the city’s first coordinated crisis response.

GayFest: It’s a thing

Inspired by the opening of Grand Avenue Mall, and the resurrection of Downtown that was expected to follow, the Grand Avenue Pub opened at 716 W. Wisconsin Ave. in August 1982. The bar sought to achieve a "Cheers" vibe on West Wisconsin Avenue – which was a tall order in these semi-blighted blocks, which included the Milwaukee Public Library, the Norman Apartments, Denmark Adult Books, Dunkin Donuts and the long-running Club Baths, 702 W. Wisconsin Ave.

The pub offered full-service lunch and dinners on weekdays and brunch on weekends. The menu was quite extensive, offering not just beer-battered fish fries and burgers, but surf and turf, prime rib and oysters. "Breakfast on the Avenue" offered sidewalk dining at a time when this was unheard of Downtown. The bar also offered all-you-can-eat spaghetti and meatballs, fried chicken and potato pancakes that were popular with the local fire department.

Today, a gay bar on 8th and Wisconsin might seem unusual, but the bar footprint was fairly scattered in 1982. The Beer Garden was still going strong near Washington Park; The Finale and Tina’s were thriving in Riverwest; Lost & Found and Essinger’s were out on 27th Street; quite a few bars were operating in the Third Ward and Walker’s Point; and of course The Factory, The Mint Bar and This Is It were all Downtown. It helped that the bar was next door to the Club Baths, which was advertising opportunities to "proudly celebrate Wisconsin’s consenting adult laws" 24 hours a day with $2 lockers.

Owner Paul Gumsey previously managed the Ozone Bar in West Allis, and now, with his partner Scott O’Meara, he was creating something new and different for Milwaukee. He was on to something amazing – if he could just hold onto it.

Celebrating the first anniversary of the bar, Labor Day weekend and gay pride overall, Gumsey announced the arrival of "GayFest" on Aug. 28, 1983. GayFest would bring Milwaukee’s "first outdoor gay festival" to the alleyway behind the Grand Avenue Pub block. Events included the crowning of Miss, Ms. And Mr. Gay Grand Avenue, body painting, water balloon fights, pie throwing, a wet t-shirt contest for the ladies and a wet jockey shorts for the guys, and much much more. Entertainment was provided by Raygirl of Club 219, Select Sound and the Who’s No Lady Review. Over 500 ears of roasted corn were served that weekend.

No attendance numbers were provided. RAGG, the only LGBT media in town in 1983, mentions "amazing turnout and a good time had by all." Said the editor in chief, "I’m sure we will see this become an annual event in the City of Festivals."

GayFest II & III: The Sequels

When Shadows (814 S 2nd St.) restaurant debuted with candlelit, romantic dinners in fall 1983, it gave Grand Avenue Pub some serious competition that it didn’t need. The M&M Club was already gay Milwaukee’s preferred place for dinners and brunches. By June 1984, there were three similar pubs competing for the same "gay dollars" with the same identical menus. While Shadows and M&M invested heavily in advertising, Grand Avenue Pub didn’t seem to advertise at all. Unfortunately, Shadows and M&M were closer to popular bars ripe for after-dinner drinks, while Grand Avenue Pub was an island unto itself.

Kitchen business began to decline, and eventually, food service was cancelled. Rumors began to circulate that Gumsey was breaking up with O'Meara and/or moving to California. By early May, media reported that Grand Avenue Pub’s doors were locked. "I had other business interests," Gumsey told InStep, "and I sold the bar at a good price."

It’s unclear whether or not Grand Avenue Pub was ever sold, but the bar did reopen – with original owners Gumsey and O’Meara, and new manager Henry Simonis – in October 1984. It’s anyone’s guess what the four month intermission was all about. Now calling itself "Milwaukee’s gay party pub," Grand Avenue invited guests to "Party on the Avenue" with the city’s longest happy hour and midnight drink specials. The formula worked, the bar regained its popularity and the restaurant business returned.

Whether or not there actually ever was a GayFest II remains a mystery. Grand Avenue Pub was closed from May to October 1984, and InStep Magazine took a summer vacation as well. There’s absolutely no media mention of any event happening in the parking lot or anywhere else.

Celebrating their joint birthday in August 1985, Gumsey and O’Meara announced their ambitious plan to host GayFest III as a three-day weekend festival. Crowds applauded, imagining the return of the fondly remembered back alley operation of 1983. However, organizers were aiming for something much bigger than a parking lot party.

GayFest III would be held in the green fields of suburban Franklin. Sponsored by BESTD Clinic, the event was designed to raise money for the Milwaukee AIDS Project. In addition to fundraising, organizers hoped the festival would create a better public perception of the gay community.

Although this was a fundraiser, it was also intended to be a festival, not a protest, march or activist event. This was a definite and marked change in tone. People were here for fun, not to fight.

With continuous entertainment from noon to midnight, the event offered many compelling activities, including a Dunk A Drag Queen Tank, 100 Yard High Heel Race, Tug of War Battles, Mr. Gay Fest competition, a drag showcase, food vendors, children’s activities, beer gardens and a dance tent. La Cage supported the event with lighting, sound and DJ equipment. A shuttle bus would transport guests from Downtown (Grand Avenue Pub) and Walker’s Point (La Cage). Three thousand people were expected to visit the grounds from Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota and even the Upper Peninsula.

GayFest III was scheduled for Sept. 14-15, 1985. When Franklin officials hassled organizers about permits, a private citizen opened up their private 50-acre parcel to host the event. It may be difficult to believe this today, but "the first PrideFest" (as it would later be remembered) made its debut at 27th and Rawson Avenue in Oak Creek.

"We’re having a big family picnic where gay people are feeling very comfortable and open," said organizer Nova Clite. "There’s room for everyone."

Bringing a gay pride event out of a Downtown alley and into the suburbs had to feel victorious in 1985. In defiance of the ever-increasing shadow of AIDS, the community was coming together in celebration for the first time in years. What could go wrong?

A noble experiment

All systems were go Friday night for the grand opening of Milwaukee’s first real gay pride festival. Thanks to a committed crew of organizers, volunteers, friends and family members, the makeshift park was ready for business. With a watchful eye on the weather forecast, everyone went to bed eagerly awaiting opening day.

At 6:30 a.m. on Saturday, Sept. 14, 1985, Jeffery Biondich drove his car onto the grounds, taking down a tent, several decorations and a series of overhead lights. Biondich had wrongfully assumed nobody was at the park at that hour. He was wrong. Due to bomb threats, overnight security patrolled the grounds. The guards halted the vehicle, apprehended the driver and engaged local police.

"He knew the gay community was assembling there, and he didn’t like it," said attorney James C. Wood afterwards. "He wanted them to know they weren’t welcome." Biondich was charged with criminal trespassing, intent to commit criminal damage and intent to commit bodily harm. In the end, Franklin police dismissed most charges and issued only a traffic citation.

Unfortunately, the local media caught wind of the incident and heavily publicized the rampage before the gates even opened. The Milwaukee Journal came to the grounds but found no sign of damages, conflict or concern at all.

"If you look around here, you’ve got normal, everyday people, students all the way to grandparents," a festival guest told the Journal. "The older I get, the more I realize that you have to raise everyone’s consciousness that we are healthy, normal, okay human beings."

Saturday’s extreme thunderstorms and the bad publicity scared off visitors, for sure. Rumors of a biker gang raiding the festival circulated through the bars. Organizers had to spend $3,000 on security staff after volunteers no-showed. This money was taken directly out of the fundraising pool, at a time when it was sorely needed to support people with AIDS.

In the end, GayFest III welcomed 1,000 guests Saturday and 2,200 guests Sunday. But was it a success?

"I wished more would have shown up," said Ron Geiman. "If only half the number of people who asked me, ‘How was GayFest,’ had actually gotten off their bar stool and shown up for themselves."

The organizers responded with an Oct. 3, 1985 editorial.

"For those of you, who for some reason could not attend, you really missed a good time for all. But then again, those who did not attend I’m sure were sitting the bars gossiping about the motorcycle gangs, the bombings, the fights and all the evils of the world that were going to befall this event. Perhaps this is the reason we did not even see our reigning Mr / Miss Gay Wisconsin at this event. Must we start a new organization within our community entitled Rumor Control? Security was at its peak, and reassure the gossips, there was only one incident that occurred and it was handled with total professionalism.

"It just amazes me that so much controversy is made as to the community supplying functions to attend. And yet, certain individuals take it upon themselves to supply the community with functions and receive little to no support ... based on what we’ve seen, we would all starve is we have to rely solely on our community for cash flow.

"Come on people, we need to be more united and support all activities and causes in our community. We need to put our prejudices and personal feelings aside and look at things on a total level. Let us stop being petty.There are still some of us who care and would like to see more activities within our community."

What was really to blame for the downfall of GayFest III? Maybe it was the rumored bomb threats, biker gangs and runaway drivers. Maybe it was the faraway location. And maybe it was still too soon for people to celebrate gay pride during daylight hours. Gay bars with windows were still new to Milwaukee, people were still using nicknames in gay bars to remain anonymous and the concept of "straight allies" visiting gay bars was years away. GayFest challenged the community to come out and be visible, but many gay people in Milwaukee just weren’t ready for that public commitment.

GayFest III promised a financial statement, and Geiman promised to publish it. "Once people see the profit isn’t going into someone’s pocket, hopefully they’ll spend less time badmouthing GayFest and more time supporting it." If the financial report was ever produced, it was never published in InStep.

And GayFest was never mentioned anywhere again, except in the fuzzy, half-memories of two community icons, over 25 years later. No photos have ever been published of this pioneering event.

One festival ends, two begin

Closing rumors continued to chase the Grand Avenue Pub throughout 1986. Food service stopped again in July. By August, the writing was on the wall. To keep the business going, operators took over the nearby Ding Dong Bar (746 N. 7th St.) and opened the "Grand Avenue Annex" with noon lunches and Friday fish fries. When licensing issues were resolved, the Grand Avenue Annex closed and the Grand Avenue Pub reopened in December 1986. To many, the switcheroo felt like a stunt for attention.

It seems that Paul Gumsey and Scott O’Meara exited the business – and possibly Wisconsin – sometime between 1986 and 1988. They haven’t been heard from since. Henry Simonis did his best to keep the bar running.

Although West Wisconsin Avenue saw a lot of demolition between 1982 and 1988, redevelopment didn’t necessary follow. Entire city blocks disappeared, eliminating residential and commercial space, foot traffic and complementary businesses. Club Baths, formerly a gay hotspot, was almost abandoned after the AIDS outbreak and the introduction of safer-sex precautions. In February 1988, the bathhouse was forced to close by city health officials.

Grand Avenue Pub lasted until July 29, 1988, when Simonis closed down, stripped the bar bare and disappeared. Rumors circulated that George Prentice of La Cage was going to buy the Grand Avenue, move the grill behind the bar and serve food open to close. However, the bar never reopened. It was demolished, along with the rest of the block, for the construction of Library Hill Apartments in 1999.

Although Grand Avenue Pub and GayFest left the landscape, neither the need for AIDS funding nor the call for community celebration were ever silenced.

"Enough people showed up at GayFest to prove it could work," said George Prentice, owner of La Cage. "It was enough to convince us to keep it going, no matter what the hassle. La Cage wanted to keep the idea of a ‘pride fest’ alive."

MAP Fest, "a celebration of gay and lesbian pride," debuted on Sept. 1, 1986. With events stretching from National Avenue to Walker Street down 2nd Street, the newborn festival was also a celebration of southern Walker’s Point as the new axis of gay life in Milwaukee. MAP Fest offered many of the same activities as GayFest, including the Dunk a Drag Queen Tank, High Heel Races and DJ Battles. The event also ran a Guess the Number of Condoms contest, with the winner taking home a brand new Honda Elite Scooter. Sponsors La Cage, Mint Bar, Your Place and Hot Legs all pledged 20 percent of register totals to the Milwaukee AIDS Project. In the end, over $5,000 was raised.

"The city gave us no problem with permits," said Prentice. "Alderwoman Mary Ann McNulty was totally supportive every step of the way. We did not encounter any hassles at all."

MAP Fest was a tremendous success that continued, in various forms, for over a decade. By offering a familiar location for the gay community and an open-air street festival format that appealed to allies, friends and family, MAP Fest crowds grew larger every Labor Day weekend. Bars opened and closed, sponsors came and went, but the old standbys like La Cage continued to support the event every year.

By September 1986, another fire had already been lit, as planning began for a second March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Organizers placed a full page ad in In Step Magazine.

"WE OF AMERICA'S LESBIAN AND GAY COMMUNITIES urgently need to bring a message to this nation and its leaders-it is not we, but the threats to us, that endanger the entire nation and its values. The agenda of our enemies is all too familiar. It's an agenda of hatred, of fear, and of bigotry-against us, against freedom, and against love. - -The escalating attacks on our community are part of a pattern of assaults on human rights. As the rights of lesbians and gays are threatened, racist attacks increase; the hard-won civil rights of People of Color are dismantled. In 1969, the Stonewall Rebellion released the pent-up yearnings that had been stilled through eons of oppression. And today, after all the suffering and all the struggling, we issued this Call for a March on Washington as we proclaim to friend and foe alike, FOR LOVE AND FOR LIFE, WE'RE NOT GOING BACK!"

Inspired by this fiery rhetoric, a group of Milwaukeeans attended the "Great March" on Oct. 11, 1987, among nearly 750,000 protestors from across the nation. Energized by the experience, they formed the Milwaukee Lesbian & Gay Pride Committee and began planning Pride Week 1988 – the first in a series of continuous annual events now known as PrideFest Milwaukee. They, too, faced harassment, threats of violence, even death threats. But they believed, and they persisted.

And thanks to their persistence, and the efforts of their successors over the past 33 years, PrideFest Milwaukee welcomes nearly 50,000 people to celebrate culture and community every June.

"Our primary task these days as gay people is to learn how to celebrate life in the face of death," said the NYC Pride Parade Marshall in 1987. By the time of the "Great March," 50,378 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS and 40,849 had already died. By the time of Pride Week 1988, 82,362 people had contracted AIDS in the U.S. and 61,816 of those people had died. It's a terrifying thought: In just a few years, AIDS had wiped out a population five times the size of my 1980s hometown.

Sometimes, it’s hard to believe LGBTQ pride was reborn during this great and crushing darkness, much less survived and thrived decades into the future. And now, three decades later, we’ve come full circle to the earliest days of LGBTQ activism, with none of the crushing doom of our ancestors.

Maybe 2020 has been a long overdue reminder that we’ve all become a bit complacent. Maybe 21st century "pride" should be more of a collision of celebration, call to action and a demand for change – the type of collision that brings thousands of diverse people into the streets instead of behind the tall gates of a park, to live proud for those who no longer can.

About the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project

Founded in 1995 as a PrideFest booth exhibit, the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project has become the state's largest digital collection of local LGBTQ history. Through digital and social outreach, the Project seeks to discover, explore, document and preserve hidden histories that might otherwise be silenced. All photo and story submissions support the ongoing efforts of the Wisconsin LGBT History Project to document, preserve and celebrate our shared heritage.

Follow the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project on Facebook and Twitter.