A few hours before he died, Louis Schmidt, Jr. went to his father’s house for Sunday dinner. The elder Schmidt had a grocery store on North 3rd Street where his son worked until he quit to embark on a new, more exciting career his father knew nothing about until he was notified the next morning that his barely 18-year-old son had been killed in a prizefight.

That was 119 years ago. Since then there have been 15 additional boxing fatalities in Wisconsin. Sixteen, if you count Dennis Munson, 24, who died March 28 after participating in an amateur kickboxing match at the Eagles Ballroom.

The official cause of Munson’s death has yet to be disclosed. Kickboxing is allowed in Wisconsin but is not regulated by the state. There was a physician at the ringside when Munson collapsed after his three-round bout.

There was no doctor on the scene when Louis Schmidt Jr.’s ring career began and ended on July 23, 1895. There wasn’t even a ring. The fight was held in the backroom of a saloon on Port Washington Road near the city limits. Schmidt and Frank Klein, wearing eight-ounce gloves, fought on the bare wood floor surrounded by chairs seating about 40 spectators who’d paid 50 cents apiece to watch.

They, as well as the combatants, were breaking the law. A Wisconsin statute enacted in 1869 specifically made participating in and watching a fight for "any prize, belt or other evidence of championship" a crime punishable by jail time.

The terms of the match arranged by Schmidt originally called for him and Klein, who was 20 and had previous ring experience, to box up to 15 rounds; but when they arrived at Henry Schuetze’s tavern at 11:30 that Sunday night they decided to go three rounds and then decide if they would continue.

Klein testified at the inquest that after "playing" with Schmidt for three rounds he asked if he’d had had enough and said he didn’t want to hurt him, but Schmidt chose to continue.

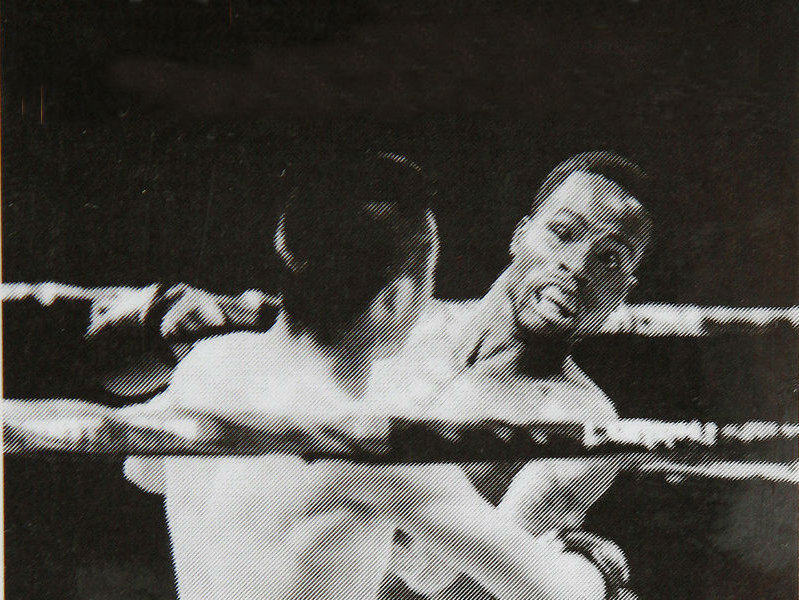

When Klein hit him with a left on the jaw in the fifth round, reported The Milwaukee Journal, "Schmidt did not even reel. He straightened out and fell like a tree, his head striking the floor and bounding like a ball."

Schmidt regained consciousness long enough to have a beer with his conqueror and divvy up the receipts of about $30 according to their agreement of 75 percent to the winner. When he collapsed again, a doctor was summoned.

Schmidt was pronounced dead at Trinity Hospital, and the post-mortem disclosed a blood clot on his brain.

"I had no intention whatsoever of hurting Schmidt," Klein said. "I can’t understand how I could have knocked Schmidt out in the first place. We used eight-ounce gloves and it is almost impossible to hurt anybody with them."

At his trial for manslaughter the following spring, Klein had a legal heavyweight in his corner. "...It is doubtful if any lawyer who has practiced at the Milwaukee bar has been more uniformly successful than" Henry J. Killilea, said "History of the Bench and Bar of Wisconsin," published two years later.

Killilea loved sports, and in 1899 he and a group that included Connie Mack and Charles Comiskey met at the Republican Hotel (now a parking lot on the northwest corner of 3rd and Kilbourn) and founded the American Baseball League. In the late 1920s, Killilea owned the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers.

After the prosecution presented its case, Killilea moved to have the charges dismissed on the ground that "no evidence had been introduced ... which tended to show that Louis Schmidt Jr. came to his death at Klein’s hands." Judge Emil Wallber denied the motion, though he assessed the evidence himself as "very slight."

After five hours of deliberation, the jury of seven farmers and five city folk found Klein guilty -- not of manslaughter, but rather fourth-degree assault and battery.

He was fined $50.

Of the 16 fighters who died as a result of injuries suffered in Wisconsin rings, maybe none suffered more than Johnny Butler, a star local amateur who fought in the early 1930s.

In a 1932 bout, he incurred an unspecified injury to his neck that didn’t kill him -- at least not immediately.

Two years later, on the night of Sept. 25, 1934, friends came to the house on South 8th Street where Butler, 24, lived with his widowed mother and a sister, and asked him to go out with them.

He declined, and as the friends left one of them admonished Butler to "quit worrying about that neck of yours."

A while later his mother went out to the garage and found him hanging from the rafters.

A note in his pocket said, "I cannot sleep. I am going crazy. Good-bye."