This series originally ran in April 2016 for Milwaukee Day, but in honor of Milwaukee's birthday, we're re-running it to highlight the 21 people, moments and ideas that have defined Milwaukee and continue to shape the city. This is part 1 of 4. Happy birthday, MKE!

1. The first people of Milwaukee: 10,500 BCE-1795

While there is evidence of pre-Paleo people living in Southeastern Wisconsin as far back as 12,500 years ago, the first recorded inhabitants of what is now Milwaukee came to the area in the late 17th Century. They represented the Menominee, Fox, Mascouten, Sauk, Potawatomi and Ojibwe tribes, all Algonquin-speaking tribes.

A century later, European settlers arrived, and in 1795, Jacque Vieau was the first to establish a permanent home in the area. While most of the American Indians were eventually forced out of the area, some have remained, the largest group from the Potawatomi tribe. Their influence on modern Milwaukee can be seen in the Indian Summer Festival, the Indian Community School and the popular Potawatomi Hotel and Casino. And, of course, we owe the name of our city to the Algonquin people.

Thanks to "Wayne's World" and Alice Cooper, we all know that Milwaukee, or "Mill-e-wah-que," is an Algonquin word for "the good land." Ask an historian or entomologist, and they'll most likely confirm that Cooper was correct. Other accepted meanings are "gathering place by the water" or "beautiful or pleasant lands." Whatever the exact meaning, the word was always spoken and not written down until European settlers arrived. Early on, it was spelled "Melleoiki" and later evolved into the contemporary spelling.

2. From fur trading to first class city: 1795

The first permanent edifice in Milwaukee was established by Jacques Vieau, a Montreal born French-Canadian fur trader who arrived in what would become Milwaukee Green Bay. Milwaukee became his summer home as he set up several more trading posts throughout Wisconsin. The location of his home, the first home in the city, is marked by a monument in Mitchell Park. It's hard to imagine a time when Milwaukee was a quiet, grassy outpost with a population of one.

3. The founders of Milwaukee: 1818-1837

In 1818, Jacques Vieau hired Solomon Juneau to work at his trading post and, in settling Juneautown shortly thereafter, became the man of Milwaukee's firsts. He built the first store, the first inn and sold plots of land to newcomers. He created the Milwaukee Sentinel, the oldest continuously operating business in Wisconsin, as well as became the city's first mayor and first postmaster. He also married Vieau's first daughter, Josette, who is considered the "Founding Mother of Milwaukee." His home sat in the spot where the Mitchell Building now stands.

George H. Walker arrived in Milwaukee in 1834 and founded the settlement of Walker's Point, where he also ran a fur trading post. He had a varied political career, which included stints as mayor in 1851 and 1853. He was also responsible for breaking ground on the city's first street car in 1859.

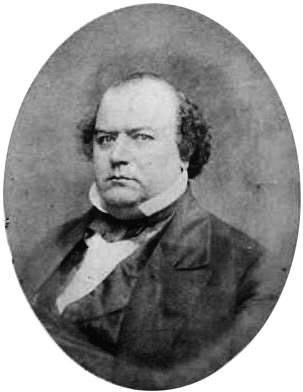

Byron Kilbourn was a surveyor when he founded Kilbourntown in 1837. His political career was varied and he served as mayor in 1848 as well as 1854. In between his mayoral stints, he became involved in the railroad industry. Kilbourn's history is fraught with conflict, being one of the key figures in Milwaukee's Bridge Wars and being accused of mismanagement and fraud of the Milwaukee and Mississippi railroad. Kilbourn also founded what became known as West Bend and the Wisconsin Dells.

Solomon Juneau, George H. Walker, and Byron Kilbourn came together to found the city of Milwaukee.

4. City rivalries culminate in the Bridge Wars: 1845

Milwaukee’s sectionalism is older than even the city itself. In the 1840s, Juneau, Kilbourn and Walker (but predominantly the first two) were striving to expand their settlements at the expense of the others’ and seeking to increase influence over their competitors. The Milwaukee River was a divide – literally and figuratively – between the East Side (Juneautown) and the West Side (Kilbourntown).

East Siders, sequestered between the river and the lake, desired access to the outside world, but the aggressively partisan Kilbourn wanted to restrict such access in an attempt to make Juneautown dependent on – and eventually incorporated by – his West Side. But not only was the river a channel of contention, it was also really inconvenient to cross.

Prior to 1840, you either had to row yourself from one side to the other or take a ferry or county shuttle. That year, the Wisconsin legislature ordered Milwaukee County to build a "good and substantial drawbridge," and despite the West Side’s opposition, a bridge was built at Chestnut Street (now Juneau Avenue). It proved so advantageous that three more were constructed – at Spring Street (Wisconsin Avenue) in 1842 and at Oneida (Wells Street) and Walker’s Point (Water Street) in 1844.

The West Siders, particularly Kilbourn, resented the bridges, viewing them as a threat to their control on travel and trade with the interior. On May 7, 1845, a board-meeting resolution by Kilbourn to remove the west end of the Chestnut Street span was dismissed by the other trustees; the next day, Kilbourntown’s end of the bridge had been dropped into the river. An East Side mob gathered and incredulity turned to incense. The village board called a meeting that evening on May 8 and, without a West Side quorum, made it illegal to "cut, remove or damage" any bridges, under the penalty of a $50 fine and five days in jail.

For two weeks, the hostility simmered, but on May 19, it turned to violence. A band of East Siders destroyed the Spring Street bridge and attempted to chop down the Menomonee River bridge, which connected Kilbourntown to Chicago. They were met with resistance by West Siders, some armed with guns, and a skirmish ensued, resulting in a couple of people being "considerably injured," according to the Milwaukee Sentinel.

After bloodshed and a small-scale civil war, the town collectively seemed to shake its head and snap back to reality, realizing Milwaukee needed access and cooperation, rather than isolation and opposition, to grow and prosper. Neither East nor West Side won the Bridge War of 1845, but Milwaukee emerged victorious as a group of citizens came together on December 3 of that year to work on a number of civic issues. Among those was forming a committee that would ultimately draft a City Charter and unite the three sects.

5. Milwaukee city charter: 1835-1846

The first Milwaukee election was held in 1835, but it wasn't until 1846 that the three-town rivalry cooled down enough to officially incorporate. Milwaukee officially becomes a city on Jan. 31, 1846 and would eventually be home to nearly 600,000 residents that span 96.1 square miles along 10.2 miles of lakefront shoreline by way of 1450.5 miles of streets.